Not, at least, from the trail of the money. He himself must have had hardly a penny.

“How did you live?”

“I got my ownself over to England on a boat and picked up work, shoveling rock or pushing sand. Day work you didn’t need a past for. When some other Nor’n Irish come along, I’d move on. Before he could start asking the questions.”

He didn’t give any specifics, and she didn’t ask.

“I saw when you got married,” he continued. “It was written up in the English papers. I saw too whose name you took. Servant of the British crown. That’s when I started feeling sure you must have done it for a reason. I took myself as far away as I could with no passport and no money to have a good one made, for a long time then. I’d seen you drawing. I knew you could do my likeness.”

“I didn’t betray you,” she said. “I’d never have done that. Not on purpose. Ed — my husband has had nothing to do with it. I never told him.”

Had he followed Edward as well? His enemy, suddenly so real, so intimately linked to his own time on this earth? Had he watched Edward leave the Residence just this morning, tall and increasingly solid in his well-made suit, seen him reach out one large manicured hand with its family ring on one finger and wedding ring on another, and open the door to the car waiting for him? Her Edward, who had protected her all these years. Her Edward, in Niall’s eyes. Had Niall shaken his head and asked himself, So, that’s what she chose?

Her Edward. Clare started at the thought. She checked her watch. In two hours, Edward would be returning, bringing the P.U.S. with him, their guests following shortly.

Everyone expected so much from her. She, of all people! She was pale, beige, remote. She was cool, calm, efficient. She had molded herself into something perfect. But she wasn’t perfect. She was anything but perfect. And still they would keep asking all these things of her. Now, here was Niall, wanting something from her also. Something she didn’t have to give him.

“Why now?” she said, sharper than she’d meant to. She softened her voice. “If you’ve been following me all this time, if you decided to risk my being some sort of British informant, why did you step up to ask me about the money now? Why today?”

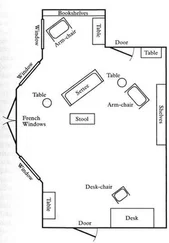

Niall cracked his knuckles and looked away. “The flowers. I stepped in here once, trying to keep out of sight, and saw right away you must come in here of your ownself, to sit. Next door to your house, and all the flowers — I told myself, this is where I’ll get her alone. No one for her to run to. But the fecking rain in Paris.”

“Today’s the first day of sunshine,” she said.

He dropped his hands and nodded.

She sighed. How could he know her so well? “Yes, but why now? If you were worried I’d turned on you, why not take the risk last spring, or last autumn, or last summer? Or ten years ago?”

Niall studied her, as though he was figuring out how much he wanted to reveal. Finally, he said, “Because when they closed down the Maze, they transferred Kieran Purcell to another prison facility, where he met a lad I’d once been working an oil rig with up in the North Sea. It was good pay, a good team, I’d stayed on longer than I should have. And they get to talking about tattoos and the ways the R.U.C. had for distinguishing Volunteers, ’cause there was a time some were getting new identities, and this guy tells Kieran he met a boy who was pretending to be from the south but was from Derry — he knew my accent, see — about five ten, black hair and eyes as light as the sky on a winter morning, who kept saying he’d been out of Ireland since 1982 and didn’t have any family there, even though everyone has family in Ireland, who had this strange scar on his neck, looked like a sickle, and what could one do about that…Ol’ Kieran, he puts it all together. So when he gets sprung this winter, he goes to my cousin and tells him he’s been wondering whether it really were me in that coffin and might it not be interesting to have the old box dug out. They’ve got all those ways now for identifying a toenail and all that, don’t they. And then ol’ Kieran says if it turns out not to be me in there, where was I, and what did my cousin know about it, because he knew my cousin was like my own brother, and we queued up together to join the Struggle, and he the one who said it were O’Faolain he pulled out of the water. And that’s when my cousin put the notice in the paper, like we agreed twenty-five years ago, if ever any trouble come on him.”

“You mean this man Kieran wants the money? If you hand it over to him, he will leave it alone? But if not…?”

“Kieran was a good man. Dedicated to the Cause. Half the years I’ve been hiding, he spent in the H Block. He’s not looking to go back in there for no good reason.”

“I don’t understand.”

“I mean they’re saying it’s all peace and good neighbors now, but people remember. One tout tried to go back a couple years ago, had been hiding in some village in England. Did you read about him? He died an accidental death soon after. And twenty years in prison, you think ol’ Kieran’s going to get a job now?”

“You mean this Kieran knows about the money that went missing and if he was to get it, he wouldn’t tell anyone you’re still alive? That your cousin covered for you?”

“Feck, Clare, I dunno. Sure, he knows about the money. Maybe he’ll keep his gob shut and disappear to Barbados. Ol’ Kieran. Or maybe he just wants to know I wasn’t fecking with them — he gave his best years to the Cause, spent them in prison, didn’t he — and will give it all to the Church. Most likely he turns it over to whoever’s still kindling a flame, and gets a pension for his woman. It’s not like my cousin was asking him to spell out his plans. You don’t feckin’ ask questions of people like Kieran. I just know he wants the money, and if he doesn’t get it, he’s going to put trouble on my cousin.”

She shifted on the bench. “But if you gave him the money and he handed it over to whomever… They’d know you were alive. Wouldn’t they, mightn’t they…?” She wasn’t sure how best to put this. “You know?”

“Come looking for me?” Niall shrugged. “If they did, I’d feckin’ well deserve it. But my cousin’ll spin them some yarn about a tout going to the R.U.C. on me and the money, and that’s why I went into hiding. He convinced everyone it was me in the coffin, didn’t he? They’re old men now, the ones who knew me. They get the feckin’ money and that will be the end of it.”

And she saw in his eyes the hesitation.

He took her hand up, looked at the palm, then laid it back down on her knee, arranging it like a mortuary worker arranging the limbs of a corpse.

“I mean,” he said, “if you still had it. If you hadn’t given it over to the wrong person.”

He stood up and shook his head.

“Forget it. Forget it.”

But it had been there. For a moment, he’d been ready to ask her. Even though he knew she didn’t have that money. She stood up, too, still exactly his height, still eye to eye. He knew about her comfortable lifestyle. “Where will you go?”

“Same place I’ve been all these years. Nowhere.” He turned to leave.

“No.”

He stopped and looked at her.

She reached her hand out and, gently feeling her way between his hair and collar, ran her finger down the slick silvery length of his scar, a familiarity she’d never dared when they were lovers.

He didn’t flinch but took her hand slowly away with his, lowered it to her side, left it there. They stood in silence, watching each other.

“You never were like the other girls, Clare. Still aren’t.”

Читать дальше