“I know,” Mathilde said, sniffing. “It’s a wonder, too. Without any decent help. And those pills you bought haven’t done anything for my fingers. Plus, working one extra evening this week.”

“Oh, Mathilde, we are so grateful. I will definitely make it up to you. And the pills, you just have to hang in there a little longer. Homeopathic medicine works a little slower. But you know that. The Swiss are masters of homeopathy. Very medically advanced people, the Swiss. Very advanced period. As well as wonderful cooks.” Clare had to avoid catching the waiter’s eye, or they both might burst out laughing. The cousin bent lower over her stalks. “I’ll go get dressed now. Send Amélie back if you need anything.”

“I don’t need anything from you, Mrs. Moorhouse,” Mathilde said. “You’re the one who keeps needing things from me.”

Clare sighed and left her staff to finish the dinner.

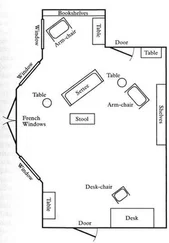

She closed the door to her bedroom and sat on the stool before the rectangular mirror on her vanity. She rubbed the crow’s feet beside her eyes and the crease that separated the top and bottom halves of her high forehead.

She laid her hands on her waist, pressing in against her abdomen. Real children had nestled within her, Edward’s children — not just pounds of paper, dollars destined someday possibly to have other children’s blood on them. Those were the only children Niall had offered her. A British diplomat’s wife with two British sons — that’s what Niall had seen today, what he’d been seeing all this time that he’d shadowed her. That’s what she saw now in the mirror. She turned her face one way and then another. The world she’d inhabited with Niall had seemed so alive, so physical. Yet what she’d had with Niall paled beside the reality of bearing children within one’s body and into this world. She wasn’t sure how it stood even against the mundane profundity of daily life. As a twenty-year-old, she wouldn’t have understood such a thought, but when she’d accepted Edward’s marriage proposal, she’d stepped through a passageway into a parallel universe where the consequences of her every action rolled out in front of her like a carpet. Wars were not fought and won based upon the countless phone calls and lists she made or instructions she issued. Multitudes of faceless souls were not saved or lost in response to her actions. But the very real people who spent their days beside her — her children, her husband, her staff — would be happy or unhappy, would be hungry or tired or satisfied or distraught. The tiny gestures that she repeated day after day sustained them. That was reality. The world Niall had shown her was a dream world that had sucked her in, in the way a nightmare does, leaving you confused in the morning as to whether you are awake now or were awake then. Niall’s world possessed a hatred too big for her heart.

You surely have beautiful hands, Clare .

She stretched out her fingers, slipping her wedding and engagement rings off, and examined the whorl around each knuckle. Two decades had passed since she’d seen Niall. He still sat with his thighs apart, his hands clasped between them. When he leaned forward, the strange streak of shiny scar tissue that ran up the back of his neck, like a sickle cropping the edge of his hairline, still pulled tight, a scar she’d always yearned to caress. The scar that had eventually betrayed him to his countryman.

“Don’t touch it,” he’d told her once. “It’s bad luck.”

“Like stepping on a crack?” Their vehicle was stopped on a highway in Maryland alongside the shore, waiting for a drawbridge to come down, third in line. She peered into the rearview mirror. Cars unwound behind them like a string of Christmas lights.

“Stepping on a crack?”

“Break your mother’s back.”

“My ma’s back already broke. From working double shifts at the shirt factory after my da was sent up. No, bad luck like the guy who tossed the petrol bomb what caused it.” He rolled his window down farther and tapped his cigarette ash onto the street.

“He got blown up with it?” she asked, resting her hands on the steering wheel, keeping her voice level. A warm wind stirred the air between them.

Niall smiled at her. “No. I broke his front tooth when we were in school because he was kissing my sister.”

She’d known he would have sisters. The Irish all had sisters. But he’d never mentioned any of them before. His words felt like a present.

He drew on his cigarette. “End of story,” he said.

The drawbridge came back down. She put in gear the little Toyota camper they’d rented under her name and inched it forward. A yellow light flashed at them as they passed over the bridge, glinting off the gold-plated band he’d given her to wear on her wedding finger. She could smell the dark water of the Atlantic.

“Go right here,” he said.

She spun the steering wheel and edged the camper out of the main stream of traffic onto a long straight road along the seaside. They headed out of the town into a sort of no man’s land, populated by grocery stores advertising beer and fireworks, and run-down motels with neon vacancy signs in pink or yellow.

The last moments of dusk dropped down over their car. Seagulls swept around them and landed on litter by the side of the road. They passed a boarded-up vegetable stand. It looked as though years had gone by since anyone had stood there. A calcified pumpkin lay riddled with holes on the ground before it.

“Should I put on the radio?” she asked.

He shook his head. In the seaside dark, she could feel his movements more than see them. But any changes of position were rare. His body had become a repository of calm in the squall growing over the Atlantic, as still as the darkness that was deepening around them. She knew him well enough now to recognize that this was his attitude of extreme concentration. She squinted at the road and kept driving. Wind pushed against the camper.

After another twenty minutes had passed, a long ugly building came into view, the worst-looking motel of all.

“Here,” he said.

“Here?” she asked.

He pointed to the motel’s vacancy sign, swinging in the Atlantic wind. “We’ll be sleeping the night here.”

She swerved into the parking lot. There were ten doors, not including the door of the reception. Only two had cars parked before them.

He was mixed up with things back home, his home, far beyond her experience, and she felt sure his unexplained absences from her aunt and uncle’s weren’t to shack up with other girls. When she’d descended the bus in New Jersey to pick up the vehicle he’d reserved and seen it was a camper, she’d felt a whisper of relief — he’d rented them a mobile hotel room. They climbed onto the thin mattress in the back of the camper, shedding all their clothes, that first night, and she’d decided: it’s just a vacation as he’d said, and she’d twirled the gold-plated ring he’d told her to wear around her finger. Each day, as they’d zigzagged the coastline, she’d permitted herself to fall further into this fantasy.

Now, though, when he told her to go into the reception and get them a room, she felt no surprise. She tucked her long blond hair up into the scarf he handed her, and put on the tinted glasses he pulled out of the bag at his feet. They smelled of his cigarettes.

“They won’t ask for your ID,” he told her.

The wind had died down. The outer door to the office was open to the warm night, but a locked inner metal guard door kept her from entering. A man with a heavy face and wearing a turban sat behind an old desk, his feet up on a crate, watching a portable TV. The only other light in the room came from a desk lamp. The turbaned man narrowed his eyes and laid one hand on a half-open drawer when she knocked on the door. His eyes squinted into the night at her.

Читать дальше