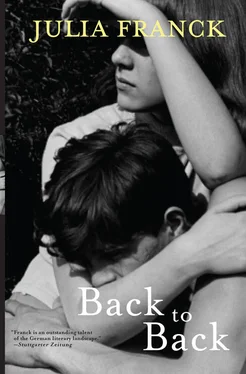

Julia Franck - Back to Back

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Julia Franck - Back to Back» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2013, Издательство: Grove Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Back to Back

- Автор:

- Издательство:Grove Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2013

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Back to Back: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Back to Back»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

, was an international phenomenon, selling 850,000 copies in Germany alone and being published in thirty-five countries. Her newest work,

echoes the themes of

, telling a moving personal story set against the tragedies of twentieth-century Germany.

Back to Back Heartbreaking and shocking,

is a dark fairytale of East Germany, the story of a single family tragedy that reflects the greater tragedies of totalitarianism.

Back to Back — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Back to Back», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Ella, it’s not about you at all, it’s not about your function. He spoke slowly and almost as softly as Marie when she calmly wished him good morning today. Was it really today? It seemed to him an eternity ago, another world, another life. Thomas rubbed his temples, he tried to catch hold of Ella’s hand as she kicked out, pushed the chair back, tore the brocade cloak off her shoulders, flung it to the floor and ran towards the door. Quietly, he said: There is no such thing as a graph without a function. I mean, well, there is, but we can represent it precisely if we know the equation.

Now Ella was opening the door, and she slammed it behind her as loudly as she could. He would go after her, not at once, perhaps in ten minutes’ time when she had calmed down. He would try to begin again from the beginning.

But when Thomas passed the closed door of Ella’s room later, he heard her laughter and the laughter of Siegfried, who had obviously dropped in for a late visit.

After changing, Thomas had arrived in the nurses’ room while it was still dark, half an hour before he came on duty and the shifts changed. He used the time to study the duty roster pinned up in a small frame beside the door. His own name was entered in the bottom column, in pencil rather than the ink normally used. Marie had tomorrow and the day after tomorrow off, and she was on night duty at the weekend. In his own column, Thomas had crosses on all the weekdays, all of them for the early daytime shift, none at the weekend. Disappointed, he turned to a chubby nurse whose eyes were red-rimmed after her night shift. Who draws up the rosters?

Matron. You don’t get any choice, specially not when you’re new here. She yawned in mid-sentence and politely put her hand in front of her mouth.

Thomas thanked her, and left the nurses’ room. It struck him that he had forgotten to wash his hands. As he rubbed them under the white stream of water, he wondered whether to bring an eraser, rub out the pencilled crosses in some unobserved moment, and then enter them in the column for night shifts at the weekend. When he returned to the nurses’ room, a woman with bobbed white hair was standing there, giving instructions in a staccato voice. Thomas shook hands with the matron and told her his name. He confirmed that Nurse Marie had shown him around the day before. The matron issued her orders briefly to the other nurses as they arrived before the shift changed. When they were all sitting at the long table, and just as the hands of the big clock on the wall moved to 6 a.m. exactly, the door opened and Marie joined the others on the bench. Her hair was immaculately pinned up, the narrow line above her eyes delicately traced. The pale rings round those eyes moved Thomas; she still hadn’t given him even a fleeting glance. News of incidents and new developments was exchanged. Marie wrote down details in the ring-bound notepad on the table in front of her. Thomas was sent out to fetch a teapot. When he came back he put the teapot down within Marie’s reach, went round the table and sat down in his own place. The nurses were discussing the new occupant of a bed; the man who died yesterday had obviously been removed. Taken away. The night shift had laid out the corpse and then taken it to pathology. Thomas thought about the pronoun. If there was no living person inside it, the dead husk became an it, not he or she any more.

Did you hear what I said, Thomas? The matron gave him a stern look.

I’m sorry. He hadn’t been listening, or if he had the last sentences had escaped him.

The matron made a note in her book, and was now clearly summing up what had just been discussed. Because of the staff shortage, Nurse Doris is on short-term loan to Ward C for the entire weekend. Thomas, you will stand in for her here. It’s a night shift, but Nurse Marie will be on duty with you. Not much usually happens at weekends, no doctors doing their rounds, no new procedures.

The morning passed in a buzz of activity. The doctor had begun his rounds, the formalities for two new admissions were concluded, preparations were made to discharge three other patients. While the matron accompanied the doctor round the ward, Marie was constantly issuing instructions, letting the nurses know who was to do what in which room. Thomas was sent over the grounds with the laundry cart, then he was told to clean a whole trolley of kidney dishes and instruments, another nurse was to help and show him how to wash the instruments, and then how to put them in a basket for sterilisation later. As she gave these instructions Marie did not look at him, but talked to her colleague who was to show Thomas what to do. Why didn’t she look at him? Thomas stood at the sink for half the morning. Many of the instruments seemed to have been lying in a disinfectant solution with a strong smell for hours, but still they were not easy to clean.

At the midday break Marie disappeared with Matron for a discussion. Only when the food trolleys were taken away and Thomas has been told to take the temperatures of a small number of selected patients for the second time did he see her again. He was just shaking the thermometer down, and smoothing out the pillow at the request of the patient, who raised his head and looked past him curiously. The door behind him had opened, and Marie was there in the room, carrying a tray of gauze, clips and a bottle. She held the tray on the palm of one hand, like a waitress, while she put a strand of hair back behind her ear with the other hand.

Can you help me with the compresses? At last she looked at him, her cheeks were flushed, her eyes shining.

She put the tray down on the bedside table of a patient whose skin had a yellow tinge; he must have a liver problem of some kind.

Thomas was to hold the patient’s arm up in the air while she tied the compresses in place. As if by chance, their bare arms touched. The scent of her intoxicated him. Motes of dust danced in the sunlight in front of her face, the light from the window fell on her shoulders, lay on her back as she leaned forward to close the compress, and briefly brushed past her face as she turned and gently touched Thomas. She held the clip of the compress in place with one hand, stretching the other out towards the tray on the bedside table. She didn’t reach for it, she would have had to grasp him more firmly and push him aside to do that.

Will you give me another clip, please?

Thomas reached behind him and handed her the clip. They stood close to each other, side by side, in silence as Thomas held the man’s arm. Marie leaned forward and clipped the compress in place, their hips touched. Thomas held the arm only a little way up in the air, so that hers could touch his when she straightened up. She picked up the tray, and he followed her out of the room. They were alone for a few seconds in the corridor.

Please don’t wait for me this evening. My husband is coming to collect me. Marie turned round, as if to make sure that no one was listening to them. He’s very jealous. If he sees me with a young man he’ll ask questions. She put the tray down on the trolley and held the brown bottle of disinfectant tincture out to Thomas. Without further explanation, she pulled the trolley of kidney dishes and instruments along behind her. Thomas followed her over to the bed. The man in it was feverish, his reddened eyes gleaming.

Spare me, he said. Marie responded with her exhausted smile. She pulled off a piece of cotton wool and handed it to Thomas, then a piece of gauze, she pushed the covers back, raised the man’s nightshirt and told him that Thomas would be seeing to him today. Thomas had to put down the tincture. Then he wrapped the gauze round the cotton wool and pressed the wad to the mouth of the bottle, waited until it was soaked, and dabbed the patient’s skin with it. The tincture had a mineral smell. The long suture on the stomach of the man, who had a childlike look, was fresh. To keep from crying out, the man drew air in through his teeth with a hissing sound, spraying saliva in pain. A second wad of cotton wool, then a third. Thomas took the kidney dish with the used wads of cotton wool and went to the door. He waited for Marie, and they tidied up the trolley of instruments together in the corridor. What had been taken out of the man, he asked, what was his operation for? Marie told him it had been for fatty liver. The affected part had been cut out and taken away. Where to, he asked, where does the bit of liver that’s been cut out go?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Back to Back»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Back to Back» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Back to Back» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.