They did another round of inspection and confiscated a few things from those who thought they were being smart.

After half an hour packed in like sardines, our breath already caught in our throats, we finally left. With the driver and his backup in the cab and seventy-two of us in the bed. The other four men stayed behind to scoop up the baggage.

We knew it once we were on our way: We were leaving our bags behind forever. Just as I was leaving behind forever my life as it had been up till then. I realized it right from the start, crushed between those unfamiliar bodies. Nothing would ever be the same. I was leaving behind Africa, my family, my land. My cocoon, big or small, good or bad though it might be. All that was left of my past was crammed inside a white plastic bag.

Was that all my life was worth up to that point? My heart told me otherwise, even as it pounded in my chest.

I held back tears, biting my lip hard. I closed my eyes in the midst of all those arms, shoulders, elbows, and I prayed to Aabe and to Allah. That they would let me find the way.

My way.

The first stretch was through the city. During those twenty minutes driving through Addis Ababa, I felt shame. A shame not divided by seventy-two but multiplied by seventy-two. I felt like a nonentity. We stopped at a traffic light, the one that led onto the national boulevard. The eyes that watched us were filled with a mixture of pity and suspicion.

Why had we let ourselves be reduced to that, they wondered.

Then we finally left the city and took the great desert highway, as everyone calls it: the big road leading to the north. At each jolt I thought my liver would burst, or my spleen, because of the dozens of elbows poking me on all sides. The city’s asphalt had given way to the usual dirt road, which, exposed to the rain and brutal sunlight, was studded with deep potholes.

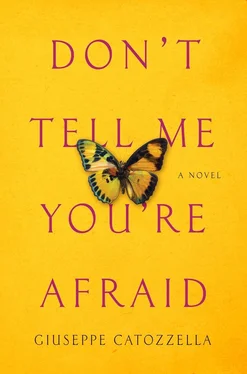

The road was absolutely straight, and we kept up a steady speed of about eighty kilometers an hour, but after a while some people began to feel sick in those conditions. I was having trouble breathing; every now and then I felt faint and had to make a superhuman effort, prying aside the others, to sit up a little and find some fresh air. I kept thinking of the wind, which Alì used to tell me to ride. Stretches of green swept by wind and graced by yellow butterflies. That’s the image I held in my mind. That’s what filled my eyes. That’s what I forced myself to picture, so as not to think.

At first no one had the courage to complain; it was more like a subdued moaning. Then the lament became louder until it spewed into vomiting.

Since we couldn’t move our arms, the vomit ended up on everyone around us. We couldn’t shield ourselves; we were windows open to the world and all types of weather.

We passed through two villages with not many inhabitants.

Those small communities had been preceded by huge, colorful billboards: a pair of lions with flowing manes and underneath the name of a travel agency advertising safaris: a big off-road vehicle, all polished and gleaming, with the inscription CAPTURE YOUR DREAMS.

At the sides of the road stood a handful of vendors exposing the vegetables or fruit picked that morning to the exhaust fumes of passing vehicles. Or wooden shacks selling potato chips, water, cookies, pretzels, juices, and chewing gum.

As we drove by, the few people on the street followed us with their eyes. Maybe they thought we were funny or ridiculous. Or maybe they were used to it and looked at us with no more curiosity than you show about a leaf that falls to the ground after being carried along by the wind. At the beginning, for the first few hours, I didn’t want to feel like I was part of the group, and I did all I could to think of it as a temporary situation. I thought about the London Olympics in 2012 and I told myself that I had nothing to do with these people. But then I gave in. I accepted the fact that this was my condition now. I had turned into a journeyer . I had no choice, if I wanted to survive.

And in any case, we had become a single body.

Each time I shifted, I had to adapt to the five or six people next to me.

Every now and then along the way, we encountered women returning from the fields with huge baskets on their heads, or groups of barefoot children chasing after nothing, who stood dazed as they watched us go by: a jeep jam-packed with people.

Around eleven o’clock that night, after ten hours, we finally stopped. In the middle of nowhere. We had turned onto a side road and followed it for thirty minutes. It was pitch dark. There was nothing anywhere except a shed.

Getting out was much more difficult than getting in.

My joints were stiff; I had a hard time bending my knees and walking. The race. The race flashed in my mind like a bolt from the blue. The older people couldn’t straighten their backs. Too many hours with their weight on the sacrum, and some hadn’t even been able to rest their feet on the floor of the bed.

With a great deal of effort they made us get out, one by one. A woman who in Addis Ababa had smiled at me encouragingly now looked at me resentfully. She didn’t recognize me. Hardened. Everyone seemed much more hardened. Withdrawn inside their armor.

We had to sleep in that shed lit by a single small, central neon fixture. The light was cold and eerie. On the floor, no mattresses. They brought the jeep in as well and closed the door.

Only then did I realize that until that moment I’d been living in suspension, as if I’d been holding my breath since the boy had come to summon me at the apartment in Addis Ababa. When they barred the door from the inside with a big bolt, and I found myself on the floor in a corner without so much as a mat, that’s when it hit me.

This was the Journey. Hodan had already gone through it.

In an instant it all came back, along with the urge to vomit. My body had become accustomed to potholes and abrupt jolts; lying still made my bowels churn. Many people threw up on the floor wherever they happened to be. I recalled people’s eyes at the stoplight in Addis Ababa: They’d looked at us as if we were worthless nobodies, as if we were mere things being transported from one place to another.

None of us had said a word; none of us had protested. In the two hours we’d spent locked in that garage in Addis Ababa, with its reek of gasoline and sweat, we had managed to efface our dignity.

Before turning off the light they handed out cereal bars and advised us to get some rest. We would leave again at dawn, in six hours, at five in the morning.

The second day was even worse. The aches and soreness, which until then had been held in check by anger, had all intensified. My right shoulder was giving me excruciating pain. Having to sit still, squashed in without being able to move, was enough to drive you crazy. After a while I began to feel the need to move. I tried and tried; the only thing I was able to do was sit up a little straighter, which was a lifesaver. I was confined in a straitjacket.

Every once in a while someone screamed into the air.

Then, after a while, he quieted down.

We passed only one village, larger than the other two. It must have been market day because the road was lined with a parade of stalls selling clothes, shoes, straw hats, sunglasses, American jeans, motor oil and windshield wipers, women’s veils, men’s turbans, cucumbers, peaches, lettuce, tomatoes, cookies, milk, Coca-Cola, you name it. It all passed swiftly in front of us like a mirage.

Someone yelled at the driver to stop, but he kept going as if he hadn’t heard.

Then the terrain turned to low-lying brush; the trees vanished altogether, giving way to scrub that was all around. Like the ever-present dust that was kicked up as we drove along, coating the jeep and our heads within minutes. That fine powder. I loved it. It was just like the dust that Alì and I used to kick up, which ended up in the old men’s shaat . I caught myself laughing. The woman next to me looked at me as if I were nuts. She didn’t approve of me. She clicked her tongue to say that I was unspeakable. I ignored her. I went on laughing to myself, lulled by memories of being safe.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)