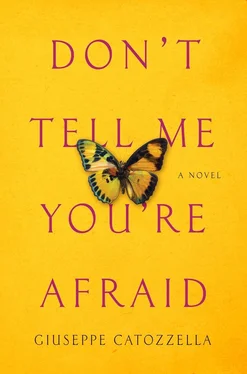

Then Alì said that the money was everything he had earned during those years, and he wanted us to have it. With a bitter smile he said that in the end he was like his father, who had wanted to compensate Aabe with money after Aabe had been wounded in his place. He knew it could not repay us, but it was the only thing he could do.

“I’ve repented, Samia. I’m out of Al-Shabaab now.”

I didn’t open my mouth.

“If you can, forgive me… abaayo…”

Silence.

Then, slowly, he stood up.

Before turning to go, he laid a hand briefly on my shoulder.

When he was almost at the door, he added: “You’ll see, you’ll make it to the London Olympics too.”

They were the last words I heard him say.

Then he was gone.

I turned around.

I was left with the image of his broad black back projected against the moonlight.

I don’t know how long I sat there like that. Motionless, with tears streaming down my face and a thousand questions like pinpricks in my head. I was confused. What Alì had told me, something he must have repeated to himself many times in the solitude of his bed, was devastating.

How could he have? How could he have forgotten all the times Aabe had held him in his arms and spoon-fed him as a child while his father, Yassin, looked after the other boys? How could he fail to recall the countless occasions when Hooyo had been a mother to him, washing and dressing him, cooking for him? How could he?

These and a million other questions raced through my mind. But I’m certain that the moment his back stood out in the moonlight was the moment I made the decision to leave.

In one instant, in that one image, my whole world fell to pieces forever. If my country had been able to make a monster out of the boy who had always been a brother to me, my soul mate, if it had turned him into my father’s killer, then that meant I was worth nothing to my country.

Aabe was Somalia. But Somalia was now dead, killed by a brother.

I was wasting my time. I had already thrown away enough years and talent in a place that didn’t want me. And that never missed an opportunity to remind me of it, subjecting me daily to shame and sweat and forcing me to endure the worst humiliations on the street wherever I went.

I had been exhausted for years, but I’d never wanted to admit it.

Hodan had been right.

I would do as she’d done.

I would do as Mo Farah had done.

The next morning I asked Said to lend me his cell phone. I called Teresa in America and told her that I would go with her. Hooyo would understand; my brothers and sisters would accept it.

“I’ve made up my mind. I’m going with you to Addis Ababa,” I told her.

HODAN WAS HAPPY about my decision, saying that I had finally found the courage to leave that country and wholeheartedly follow my dream. In the meantime, she and her husband, Omar, and Mannaar had moved to Helsinki, where the government would soon provide them with a house and a monthly allowance.

Mannaar was my joy. At almost a year and a half she was still identical to how I had been at her age. Sassy, with animated eyes, a tall, skinny beanpole. Hodan would do everything she could to enroll her in an athletics class once she turned two, which was actually common practice up there.

I didn’t want even one shilling of Alì’s money. Together Hooyo and I decided that she would keep half and the other half would go to Hodan for Mannaar. Not a single day should be wasted. We would know soon enough if she really had talent, but meanwhile she would be given the best possible start, and maybe she would get to her first race with the body of Veronica Campbell-Brown. She would win more races than me, and earlier than I had.

The endless wait for the documents required to leave the country was marked by an infinite tenderness that I had begun to feel for everything that was closest to me, for my brothers and sisters, for Hooyo, and for all my usual places. One day I even burst into tears with Abdi during a break in our training session: Sitting in the middle of the field, I told him that I would miss him and the CONS stadium so much.

“How can you miss a track full of bullet holes?” he asked me as he retied his shoelaces and got ready to start running again. True. Yet I knew that I would miss everything, and I lived each hour trying to absorb as many memories as possible, soaking up details that would be precious to me.

Another afternoon the same thing happened to me at Taageere’s bar when he insisted that I drink a shaat with him. “Soon you will go,” he said. And I burst into tears again. “Don’t cry, little champion,” kind old Taageere continued as he poured a little milk in the tea; his face was furrowed with wrinkles so deep that it looked like one of those masks representing Iblis, the devil. Except that he had gentle eyes turned down in an expression of constant compassion. “When you get there, you will quickly forget us. And when you come back, you’ll be so famous that you won’t even have time to come and say hello,” he said as he finished stirring the shaat . “If you don’t, I swear I will come to your house and make you tell me everything, one way or another.” I ended up crying on his shoulder, releasing some of the anxiety that clenched my stomach. He hugged me, then considerately changed the subject, speaking softly as always.

It took me six months to leave. That’s how long was needed to arrange for my expatriation papers.

Teresa had overseen the whole process from afar, and when the time came she returned to Mogadishu. She had become my guide and mentor. I had decided to put myself in her hands. Teresa was only twenty-six years old, but she already had a lot of experience, had lived in many countries, and knew her way around. I had finally decided to stop resisting and trust her. She was my passport to freedom.

The day I said good-bye to Hooyo and my brothers and sisters was very sad. Unlike Hodan, who had surprised us all with her departure, my leave-taking went on for a whole day, starting the afternoon before. I would be back before long, I kept saying; Ethiopia wasn’t far away. As soon as I started winning more international competitions, I would have enough money to come and go whenever I wanted.

I took only the essentials with me: almost nothing, as usual. My racing outfit. The tracksuit. A few shillings. Aabe’s headband and the photo of Mo Farah, which I’d taken off the wall after ten years. By now the page was tattered. It was no longer paper; it was an image and a dream printed on butterfly wings. The two medals from Hargeysa were left there, hanging from a nail now rusted by dampness. As she’d done with Hodan, Hooyo gave me a handkerchief with one of the shells that Aabe had given her many years ago. She wanted me to carry it with me always: It was her protection. She folded the cloth into a band and tied it tightly to my wrist with two knots. Hidden between the folds, the tiny shell couldn’t even be seen.

“That way you’ll carry your beloved sea with you,” she told me. “The entire sea in this seashell.”

Teresa had to wait awhile for me in the taxi before I could tear myself away from Hooyo. I couldn’t help it; I just couldn’t leave her. Finally I clenched my fists, gave her one last kiss, and went to confront my new destiny like a soldier or a warrior going off to battle.

We would travel by plane and would land, after a two-hour flight, at two in the afternoon.

It was the second time I had been taken to the airport by car, and this time my frame of mind was very different. I didn’t even need a sleeping pill for the flight. I was so sad that I wasn’t afraid of anything. Fear is a luxury afforded by happiness.

Читать дальше

![Ally Carter - [Gallagher Girls 01] I'd Tell You I Love You But Then I'd Have to Kill You](/books/262179/ally-carter-gallagher-girls-01-i-d-tell-you-i-lo-thumb.webp)