Deep down, I think my Noe wasn’t just blunt. She had a sharper psychological instinct than those women who think they know it all, who think they’re wise owls: the humanitees, Noelia called my colleagues at the institute, with a double ee. The humanitees thought — like almost all the humanities graduates, including me — that they were better than everyone else. ‘Just that little bit more sensitive, that little bit more humane than the rest of humanity,’ is how my wife put it. The humanitees turned their noses up at Noelia because she spoke openly about how much TV she watched in her — rare — free moments. But really they were deeply envious of her career, which was solid as a rock and way — but really way — better remunerated. They pitied her for not having children, but deep down envied her independence; the same independence they’d been so quick to boast about in their youths before trading it in for little Timmy, Tommy and Tammy, and a jealous husband. You can’t ask a humanitee if she likes cooking, because she’ll accuse you of protracting the phallocentric patriarchy. On the other hand, if she finds out that the man in a couple takes care of the cooking — as is, or was, the case in our house — she’ll only ever see him as a hen-pecked husband.

The humanitees have very clear codes when they want to flatter one another, and are the undisputed champions of the backhanded compliment. If she doesn’t think much of someone, a humanitee will say, ‘She’s a real fighter.’ But a woman she admires is ‘the boss of herself’. Noe once whispered in my ear, ‘Of course she is, because a humanitee could boss her way out of a paper bag.’

‘The humanitees wear indigenous Mexican outfits, but designer, you know the type?’ And yes, I knew the type, or I didn’t but Noelia taught me to see them that way. She could smell the male intellectual’s thinly disguised machismo a mile off, while the humanitees were blind to it. I — who was known to be happily married, am ugly, and know how to pretend I’m listening — almost always caught wind of who was all over who from the secretaries, and tried to retain the information, at least until dinner time, so I could pass it on to Noelia, because she loved that kind of thing: it was like steak to her scandalmonger’s soul.

‘Poor thing,’ she’d say of the humanitee-lover in question, ‘this is going to end in tears.’

‘What makes you say that?’ I’d ask, genuinely clueless.

‘Oh, Alfonso, because he’s clearly one of those men who buys his woman roses only to prick her with the thorns.’

And I’d nod, and purse my lips.

Was it dishonesty, all this pretending I knew the type? Of course, but of the generous, unselfish kind: the kind that makes marriages last.

‘He’s one of those people who nods to make it look like he’s following the conversation, you know the type?’

I know it well. And, Noe, now that you’re around here somewhere, let me tell you that yesterday in a bookstore café I saw a book called Oh Lord, Won’t You Make Me a Widow , and it gave me a profound feeling of pity, the kind I haven’t felt for such a long time, other than toward myself. I’d rather have my clean pain than the dirty pain of wishing for pain.

‘What’s it about?’

‘I don’t know. I didn’t buy it.’

‘And what’s all that crap about clean pain?’

‘It’s something Agatha Christie told me. When you and Luz died she decided to borrow every book on death and grief she could find in the library, then she’d come over to give me a weekly round-up of her findings. One Sunday she brought a Zen manual and explained to me that our grief, hers for her sister and mine for you, constituted clean pain. But if, for example, we’d been hurting because a boy we liked wasn’t into us, well that was dirty pain, because it was no more than an invention, a pain made up in our heads, because in fact we didn’t know, nor could we ever really know if the boy in question was into us or not.’

‘Oh, that’s so cute.’

‘I know, right? And I asked her if she liked the boy in question but she went all skittish and started reading koans out loud. I might buy that book. Not the Zen manual, the one about the widow, to tell you about it.’

‘Go for it, love, but don’t eat in that café anymore; you know those cheap wholegrain muffins are full of trans fats.’

‘You’re right, I’m better off making a little soup.’

‘Attaboy. And give The Girls a bath, will you? They’re losing the glow in their cheeks.’

*

‘There are two basic human conditions,’ Noelia liked to explain during her most conflictive decade around the issue, and usually on her second tequila. ‘Being a child and being a procreator.’

I’d nod. She’d go on.

‘I choose to experience just one of the two conditions. Does that mean that in some way I’m choosing to be only half? It’s a complicated equation, socially speaking. If you participate in both conditions, it’s like you’re two people: you’re a daughter and a mother. I choose to be no more than one, no more than one person. There’s a fair amount of coherence in that, isn’t there? Well, not for other people. For other people, being no more than one person is like being less than one. Though not if you’re a man, of course. No, that goes without saying. I’ll put it in female terms: if you’re no more than one, one woman, they assume you’re fulfilling half of your human condition, or female condition, if you like. The point is — don’t walk away, Alfonso —, if you’re one, you’re half. Now tell me where’s the logic in that.’

‘I didn’t make the rules,’ I’d say.

‘But you are an anthropologist.’

‘Yes, but I study pre-Hispanic diets.’

*

The sweater.

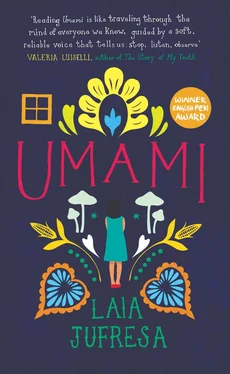

A few days ago, Linda walked into the bar carrying something yellow in her hands. When they brought her her vodka, we made a toast and she spread it out on the table. It was a small sweater. Next she pulled out a sewing kit from her bag, and from the sewing kit a needle, some scissors, and half a dozen spools of thick thread. While we sipped our drinks she embroidered diamonds, squares, circles and semicircles onto the sweater at random. At a certain point she passed it to me. I pulled back my chair and lay the sweater out on my lap. It was bigger than the clothes I usually buy for The Girls, but sat snug over my knees. It was dirty. I ran a finger over the newly sewn shapes; the taut stitching felt soft compared to the sweater itself, which was itchy. It looked like something from another era, like the knee-length socks and the micro shorts we used to wear in my day. Nobody knits itchy sweaters anymore, especially not for children. I pulled off my ring and passed it to Linda. She ran her finger around it, but didn’t put it on. Then she read the inscription inside and asked, ‘Umami?’

‘Umami is one of the five basic flavors our taste buds can identify. The others, the ones we all know, are sweet, salty, bitter and sour. Then there’s umami, more or less new to us in the West. We’re talking a century or so. It’s a Japanese word. It means delicious.’

I stopped to draw breath and the two of us laughed because I’d blurted all of this out in one go, like one of those machines in Italian churches you feed money to illuminate the altarpiece for a minute. Linda gave me back the ring. I gave her back the sweater, and she threaded the needle with purple cotton. Linda lives in the mews; I must have explained umami to her a hundred times, and in a far less robotic manner. In any case, ever generous, she rested the needle in the sweater and calmly asked, ‘What does it taste of?’

‘That’s the thing,’ I told her. ‘Since we don’t recognize the taste, the best way for me to describe it is as something to get your chops around, something satisfying. In English they say seivori.

Читать дальше