‘Your stage name?’

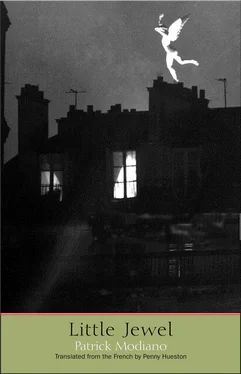

I wondered if I should start from the beginning and tell him everything. My mother’s arrival in Paris, the ballet school, the hotel on Rue Coustou, then the one on Rue d’Armaillé, and my own first memories: the boarding school, the truck and the ether, that period when I wasn’t yet called Little Jewel. But I had revealed my stage name to him, so it was better that I stick to when my mother and I ended up in the big apartment. It wasn’t enough for her to have lost a dog in the Bois de Boulogne. She had to have something else that she could show off like a piece of jewellery: that’s no doubt why she gave me my name.

He remained silent. Perhaps he thought that I was now diffident about continuing, or that I had lost track of my story. I didn’t dare look at him. I stared at the green light in the middle of the radio set, a soothing phosphorescent green.

‘I’ll have to show you some photos…Then you’ll understand better.’

And I tried to describe the two photos taken on the same day, the two head shots: ‘Sonia O’Dauyé and Little Jewel’, taken for a film in which my mother had been hired to perform, having never been a professional actress before. Why was she hired? And by whom? She wanted me to play the role of her daughter in this film. She was not the leading actress, but she insisted that I stay close to her. I had replaced the dog. For how long?

‘What was the name of this film?’

‘ The Crossroad of the Archers .’

I replied without hesitation, but they were like words we learn off by heart in childhood — a prayer or a song recited from beginning to end without our ever really grasping the meaning.

‘Do you remember the shoot?’

I had to arrive very early in the morning. It was a sort of huge warehouse. Jean Borand had taken me there. Later, in the afternoon, when I had finished and could leave, he had driven me to the nearby Buttes-Chaumont park. It was very hot: it was summer. I had performed my part; I never had to go back to the warehouse again.

I had to lie on a bed, then sit up and say, ‘I’m scared.’ It was as simple as that. Another day, I had to keep lying on the bed and flip through a photo album. Then my mother came into the bedroom, wearing a diaphanous blue dress — the same dress she was wearing when she left the apartment on the evening after losing the dog. She sat on the bed and looked at me with big sad eyes. Then she caressed my cheek and leaned over to kiss me; I remember we had to do it several times. In everyday life, she never showed the slightest bit of affection.

He was listening closely, and wrote something on his pad. I asked him what it was.

‘The title of the film. It would be fun for you to see it again, don’t you think?’

Over the past twelve years, the idea of seeing the film again had not even occurred to me. For me, it was as if it had never existed. I had never mentioned it to anyone.

‘Do you think it would be possible to see it?’

‘I’ve got a friend who works at the cinematheque. I’ll ask him.’

Now I was worried. I was like a criminal who, with time, forgets her crime, even though incriminating evidence remains. She lives under another identity and her appearance is so changed that no one recognises her. If someone had asked me, ‘You weren’t Little Jewel, were you, a while ago?’ I would have replied no, and I would not have felt as if I were lying. That July day when my mother took me to the Gare d’Austerlitz and hung the label around my neck — Thérèse Cardères, c/o Mme Chatillon, Chemin du Bréau, Fossombronne-la Forêt — I knew it would be best to forget Little Jewel. Indeed, my mother had made a point of telling me not to speak to anyone or say where I had lived in Paris. I was simply a boarder coming back on holiday to her family in Chemin du Bréau, Fossombronne-la-Forêt. The train left. It was crowded and I was standing up in the aisle. It was lucky I was wearing my label, otherwise I would have got lost among all those people. I would have forgotten my name.

‘I don’t really want to see the film,’ I said.

The other morning, I’d been terrified by something I heard a woman say at the next table, in the café at Place Blanche: ‘The skeleton in the cupboard.’ I felt like asking Moreau-Badmaev if, over time, film stock decomposes like corpses. In that case, the faces of Sonia O’Dauyé and Little Jewel would be eaten away by some sort of fungus and their voices would not be heard again.

He told me I looked pale and suggested that we have dinner nearby.

We walked down the left-hand side of Boulevard Jourdan and entered a large café. He chose a table in the indoor terrace.

‘Look, we’re right opposite the Cité Universitaire.’ He pointed to a building on the other side of the boulevard that looked like a castle. ‘The students from Cité Universitaire come here and, because they speak all sorts of languages, they call this café Babel.’

I looked around the café. It was late and there weren’t many people.

‘I often come here and listen to people speaking their different languages. It’s good practice for me. There are even Iranian students but, unfortunately, none of them speaks Persian of the plains.’

At that time of night, they were no longer serving meals, so he ordered two sandwiches.

‘And what would you like to drink?’

‘A whisky, neat.’

It was at about this time the other night when I’d gone to Le Canter, in Rue Puget, to buy cigarettes. And I remembered how much better I’d felt after they’d made me drink the glass of whisky. I could breathe better; the anxiety had dissipated, along with the heaviness that was suffocating me. It was almost as good as the ether from my childhood.

‘You must have had a good education.’

I was worried that my voice might be tinged with envy or bitterness.

‘Only the baccalaureate and the School of Oriental Languages.’

‘Do you think I could enrol in the School of Oriental Languages?’

‘Of course.’

So I would not have told a complete lie to the pharmacist.

‘Did you pass the bac?’

At first I wanted to say yes, but it was too stupid to lie again now that I had confided in him.

‘No, unfortunately.’

I must have looked so ashamed and upset that he shrugged his shoulders. ‘It doesn’t really matter, you know. Lots of amazing people don’t have their bac.’

I tried to remember all the schools I’d been to: the boarding school, to begin with, from the age of five, where the big kids looked after us. What had happened to Thérèse since that time, long ago? She had at least one distinguishing feature I would have recognised: the tattoo on her shoulder, which she told me was a starfish. And then I’d been to Saint-André, when I lived with my mother in the big apartment. But, after a while, she started calling me Little Jewel and wanted me to have a role alongside her in the film, The Crossroad of the Archers . I was no longer attending Saint-André. I also remember a young man who looked after me for a very short time. Perhaps my mother had found him through the red-headed fellow at the Taylor Agency who had sent me to the Valadiers. One winter, when it was snowing heavily in Paris, the young man took me tobogganing in the Trocadéro gardens.

‘Aren’t you hungry?’

I had just drunk a mouthful of whisky and he was looking at me anxiously. I hadn’t touched my sandwich.

‘You should eat something.’

I forced myself to take a bite, but I had real trouble swallowing. I drank another mouthful of whisky. I wasn’t used to alcohol. It tasted bitter, but it had started to take effect.

Читать дальше