A dog. A black poodle. Right from the start, he slept in my room. My mother never looked after him and, moreover, would have been no more capable of looking after a dog than a child. No doubt someone had given her the dog as a present. For her, it was nothing more than a fashion accessory that she must have got bored with quickly. I still wonder by what twist of fate that dog and I ended up together in the car. Now that she was living in the huge apartment and her name was Sonia O’Dauyé, she probably needed a dog and a little girl.

I used to go for walks with the dog, beyond the apartment block and all the way along the avenue, down to the Porte Maillot. I can’t recall the dog’s name. It wasn’t a name my mother had given him. It was around the beginning of the time I went to live with her in the apartment. She hadn’t yet enrolled me in the Saint-André school and I wasn’t yet known as Little Jewel. Jean Borand collected me on Thursdays and took me to his garage for the whole day. And I kept the dog with me. I knew already that my mother would forget to feed him. I was the one who got food ready for him. When Jean Borand came to collect me, we took the metro, and smuggled the dog onto the train, too. We walked from the Gare de Lyon to the garage. I wanted to remove his leash. There was no chance of him getting run over; there were no cars in the streets. But Jean Borand warned me not to take off his leash. After all, I had almost got run over by a truck in front of the school.

My mother enrolled me in Saint-André. I walked there alone every morning, and I came home every evening at around six. Unfortunately, I couldn’t take the dog to school, even though it was very close to the apartment, on Rue Pergolèse. I found the exact address on a scrap of paper in my mother’s diary. Cours Saint-André, 58 Rue Pergolèse. On whose advice did she send me to that place? I stayed there all day long.

One evening, when I got home to the apartment, the dog wasn’t there. I thought my mother had gone out with him. She had promised me that she’d walk him and feed him, tasks I’d already asked the cook to do, the Chinese man who prepared dinner and brought my mother a breakfast tray to her room every morning. My mother came home a bit later, without the dog. She said she’d lost it in the Bois de Boulogne. She had the leash in her bag and she handed it to me as if to prove that she wasn’t lying. Her voice was very calm. She didn’t look sad. She seemed to think it was all quite normal. ‘You’ll have to make up a lost-dog notice tomorrow, and perhaps someone will return him.’ She took me to my room. But her tone was so calm, so blasé, that I had the feeling she was preoccupied with something else. I was the only one who thought about the dog. No one ever brought him back. I was too scared to turn out the light in my room. Since the dog had been sleeping with me, I wasn’t used to being by myself at night, and now it was even worse than at boarding school. I pictured him in the darkness, lost in the middle of the Bois de Boulogne. That same evening, my mother went out, and I still remember the dress she was wearing. It was a blue dress with a veil. That dress has appeared in my nightmares for a long time, always worn by a skeleton.

I kept the light on all that night, and every other night. I never stopped being frightened. It would be my turn after the dog’s, I was sure of it.

Strange thoughts came into my mind, so muddled that I waited ten or so years for them to take shape, before I could put them into words. One morning, sometime before seeing the woman in the yellow coat in the corridors of the metro, I woke up with a sentence running through my head, one of those sentences which seem incomprehensible, because they are the last shreds of a forgotten dream: You had to kill the Kraut to avenge the dog .

I GOT HOME to my room in Rue Coustou around seven in the evening, and I wasn’t up to waiting until Wednesday for the pharmacist to come back. She was out of town for a couple of days. She had given me a telephone number in case I needed to speak to her: 225 Bar-sur-Aube.

In the basement of the café in Place Blanche, I asked the cloakroom woman to dial 225 Bar-sur-Aube for me. But the second she picked up the receiver, I told her not to bother. All of a sudden, I could no longer bring myself to disturb the pharmacist. I bought a token, went into the booth, and ended up calling Moreau-Badmaev’s number. He was listening to a program on the radio, but he asked me to come over anyway. I was relieved to know that someone was happy to spend the evening with me. I was loath to take the metro to the Porte d’Orléans. I was scared of changing trains at Montparnasse-Bienvenue. The corridor was as long as the one at Châtelet, and there wasn’t a moving walkway. I had enough money to take a taxi there. Once I was in the taxi at the top of the line in front of the Moulin Rouge, I suddenly felt at ease, just as I had the other evening with the pharmacist.

The green light of the radio set was switched on, and Moreau-Badmaev was sitting against the wall, writing on a pad, while a man with a tinny voice spoke in a foreign language. This time, he said, he didn’t need to write in shorthand. The man was speaking so slowly that he had time to write out the words. Tonight, he was doing it for pleasure and not at all for work-related reasons. It was a poetry reading. The program was being transmitted from somewhere faraway, and from time to time the man’s voice was muffled by static. He stopped talking and some harp music came on. Badmaev held out a piece of paper that I have treasured to this day:

Mar egy hete csak a mamara

Gondolok mindig, meg-megallva .

Nyikorgo kosarral öleben ,

Ment a padlasra, ment serénye n

En meg öszinte ember voltam ,

Orditottam toporzékoltam .

Hagyja a dagadt ruhat masra

Emgem vigyen föl a padlasra

He translated the poem for me, but I’ve forgotten what it meant and what language it was written in. Then he lowered the volume on the radio, but the green light stayed on.

‘You seem a little out of sorts.’

He was looking at me so considerately that I felt at ease, just as I had with the pharmacist. I wanted to tell him everything. I described the afternoon I’d spent with the little girl in the Bois de Boulogne, Véra and Michel Valadier, going back to my room in the Rue Coustou. And the dog that was lost forever almost twelve years ago. He asked me what colour the dog was.

‘Black.’

‘And have you spoken to your mother about it since?’

‘I haven’t seen her since then. I thought she’d died in Morocco.’

I was ready to tell him about coming across the woman with the yellow coat in the metro, about the large apartment block in Vincennes, the staircase and Death Cheater’s door, where I hadn’t been bold enough to knock.

‘I had an odd childhood…’

He listened to the radio all day long, taking notes on his writing pad. So he might as well listen to me.

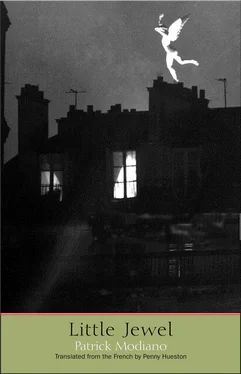

‘When I was seven years old, they called me Little Jewel.’

He smiled at me. He probably thought that was a delightful name for a little girl. I bet his mother gave him a nickname that she whispered in his ear before kissing him goodnight. Patoche. Pinky. Poulou.

‘It’s not what you think,’ I said. ‘It was my stage name.’

He frowned. He didn’t understand. At that time, my mother also had a stage name: Sonia O’Dauyé. After a while, she had given up using her assumed title, but the little copper plaque, which read COMTESSE SONIA O’DAUYÉ, had remained on the apartment door.

Читать дальше