Three months into the expedition, weak from dysentery, dehydrated, shivering with cold sweats, cursing the Jesuits who had come with him so far, and would go no further, my great-grandfather followed the example of King Chokery’s subjects, the guides who punted him down the dark, creeper-enclosed tunnel of that Stygian river: he took to chewing the leaf.

Coca, from which the invaluable drug, cocaine, is obtained, is a native of this locality. It is a plant not unlike the Chinese tea, though scarcely so sturdy in habit, growing to a height of from four to five feet, with bright green leaves and white blossoms, followed by reddish berries. The leaves are plucked when well matured, dried in the sun, and simply packed in bundles for use or export. Of the sustaining power of coca there can be no possible doubt; the Chunchos seem not only to exist, but to thrive, upon the stimulant, often travelling for days with very little, if anything else, to sustain them. Unquestionably it is much superior and less liable to abuse than the tobacco, betel, or opium of other nations. The Chuncho is never seen without his wallet containing a stock of dried leaves, a pot of prepared lime, or the ashes of the quinua plant, and he makes a halt about once an hour to replenish his capacious mouth. When I decided, driven by physical necessity, to make a trial of the native habit, I found the flavour bitter and somewhat nauseating at first, but the taste is soon acquired, and if not exactly palatable, the benefit under fatiguing journeys is very palpable. Cold tea is nowhere, and the best of wines worthless in comparison with this pure unfermented heaven-sent reviver.

No leaves on the Eastbury Level, the Hornchurch Marshes, the old firing ranges with their overgrown butts and tattered distance markers: hybrid vegetation, unloved, ungrazed. Thorn bushes. Nettle beds. Nothing to chew. By river, through Tilbury and Silvertown, doctored coca, a synthetic, is smuggled ashore. By container transporter, by white van, by Special Boat Squadron inflatable: sustenance and stimulation for Sherlock Holmes and Dr Freud. Cargo for illicit Range Rovers.

The balsa, a few twigs roped together, is punted, now drifting, now spinning on the current, towards the white zone. The blank on the map. Noises of the jungle. Shrieks and long silences. The pole sticking in mud. Jimmy parks his Volvo beside Rainham Creek, sleek black crows gather in a naked tree, black plastic flapping on razor wire.

Like my lost roll of film, out there on the Thames, two journeys overlap: Peru and Essex. Mr Stevenson was in no condition to make his report to the commissioners. He recuperated on the coast, prematurely aged, mimicking the old men, staring for hours at the Channel. Salt-smeared windows framed by faded velvet curtains. Persuaded to take the air, an afternoon constitutional, Stevenson refused to walk along the promenade; he turned his back on the sea, retreated uphill, under an ornate arch, into a small park. He liked the flowers, their teasing scents, regimented profusion: rhododendron, hibiscus. The park, with its gentle microclimate, was a grey-filter Ceylon.

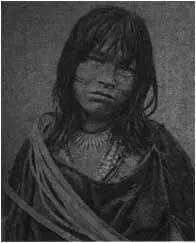

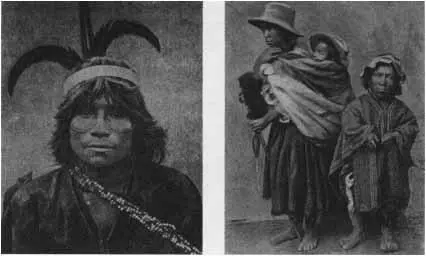

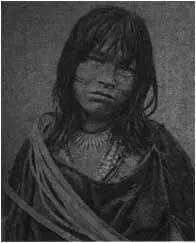

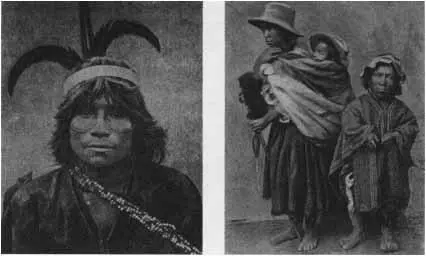

He reached into the pockets of his long chalky coat and drew out my great-grandfather’s pen-and-ink sketches; as if, by handling them, he could remember what happened, those last days on the Rio Perene. The photographs — King Chokery, the Cholo Highlanders (like dwarfish and displaced Scots), the grave goods, the cathedral square in Lima — had returned to London with Stevenson’s overheated and incomplete report. Acting on some nervous instinct he retained the botanical sketches. Now, in the early-evening chill of an English park, the drawings brought back happier days in Colombo, visiting tea-estates to gather material for articles published by the local press, the Ceylon Observer and the Tropical Agriculturalist . My great-grandfather’s minimalist representations of humble verbena, lobelia, oxalis, calandrinia, substituted for the empty beds in this south-coast garden, the tin labels that designated future plantings.

I took the phone call late on the Sunday before Christmas, suicide’s eve. You can hear the third gin being poured at the other end of the line, as old folk, solitaries, survivors, work through outdated address books. The second wife, tennis partner, of my great-grandfather’s second son’s only boy, had inherited that early Kodak portable. There was no one else. It should come to me. We’d never met, but my number was in the book. The old lady was in sheltered accommodation, very nice, very warm, a jolly Christmas in prospect: I could hear James Stewart ya-yawing in the background. The camera, that came back from Peru with Stevenson, had passed down through the generations, looked after, polished and put away in the cupboard. Then this woman, no connection of mine by blood, a lovely, no-nonsense (by the sound of it) South Londoner, took her prize possession to a charitable Antiques Road Show, in the church hall. It was certainly worth something, the man with the bow tie said, not in cash necessarily, but as part of a ‘fascinating’ tale. It should be placed in safe hands, the memory should be preserved, of that adventure in … where was it? … South America, Mexico? And, by the way, he enquired with studied emphasis, did she realise that there was film in the camera? Unexposed film. This was the thing that haunted me, that kept the Peruvian expedition running alongside my trip with Jimmy and the girls to Rainham Marshes. The impulses responsible for those pictures, the heat that caused the shutter mechanism to be pressed, was still active. Floating, unresolved, along the soft verges of the A13.

‘Lovely to talk to you, dear, so lovely. One of the ladies here, her daughter’s getting married at Easter, in church, will send you the camera. My husband, your father’s first cousin, wanted you to have it. He always said so. But we weren’t in touch, were we? And then when I heard it might be valuable, well …’

I was caught off-guard. I stood with the phone in my hand, long after the connection had been broken. I knew that the parcel would never arrive. And I knew that the mystery of those final undeveloped images would never be solved. Next morning, back from a short walk, sitting at my desk, glass in hand, gesture to the season, I remembered. I hadn’t asked for a number, an address. I didn’t even know the old lady’s name. The nuisance of it, my stupidity, ruined my Christmas curry, the traditional cigar and tape of Bresson’s Pickpocket.

The girl Track had disappeared. On the marshes. After searching for thirty or forty minutes, until the rain forced us back to the car, we left her to it, retreated to a truckers’ café in Thurrock. Track did this all the time, Livia said. Jimmy, in loco parentis, was unfazed. Track was five years older than his current wife. She’d grown up on European art cinema, Monica Vitti stalking Lea Massari. In her Oxfam way, the American was a bit of a drama queen. Right set, right reaction: absence.

In Hackney it was cats. Nailed to trees, photocopied portraits. Rewards. People didn’t disappear, not for a second time: they were the disappeared, it was their vocation. Bodies showed up in parks and squares, killers vanished. Crimes were unsigned, uncredited. Random conjunctions inspired by the location. Women, men too, travelled to the coast if they wanted to shed their identities. You saw the faces, years older, in shop windows.

Читать дальше