It was as difficult to dislike Howard Marks as it was to take the right photo. That’s why I left the film so long in the camera, an abandoned essay. Huge smile (new teeth better than the originals), expansive gestures. A girl in a scarlet PVC raincoat, bottle blonde, sitting with him at the table, was pretending, for the purposes of a documentary film, to be the interviewer. Neither acting nor reacting, she was a more potent reality than the Marksian hologram with its Mediterranean tan, twinkly eyes and contradictory semaphore of hands and shoulders. The mobile bleeped at regular intervals.

So our night voyage on the Thames, dark dreams, lapped over this sunlit room in Earls Court: arbitrary juxtapositions. The film, lost in the bilges, was busy in my memory. Soft evidence transformed into fiction. The image you don’t have, mislaid by chemist, stolen camera, retains its malignancy. It is unappeased. Marks talking, girl listening (with an expression of cynicism, boredom, that is impossible to quantify). The passengers and crew on a small craft, making no headway against a running tide, are tormented by fantasies of death by drowning. A blank sheet in my typewriter. Two stories lost. Two stories that got away. The burning chimneys of the Esso oil refineries at Purfleet. The spontaneous combustions of the landfill site on Rainham Marshes. Seen from the river. The yarns Howard Marks spun, conspiracies, coincidences, scams, going up in smoke. Sound lost with image.

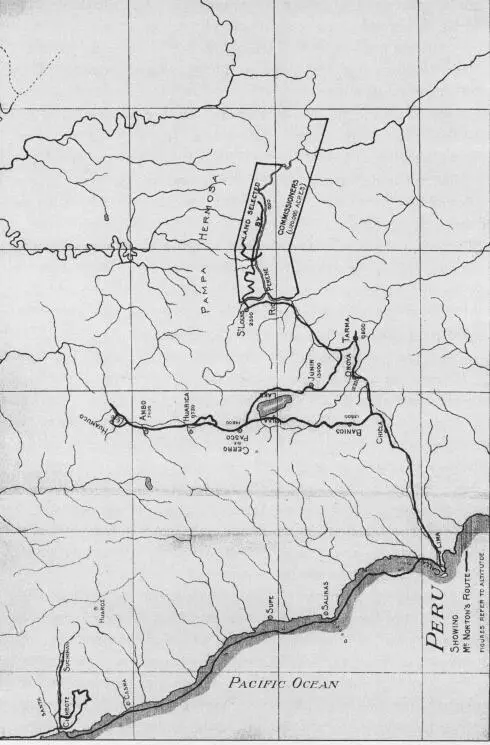

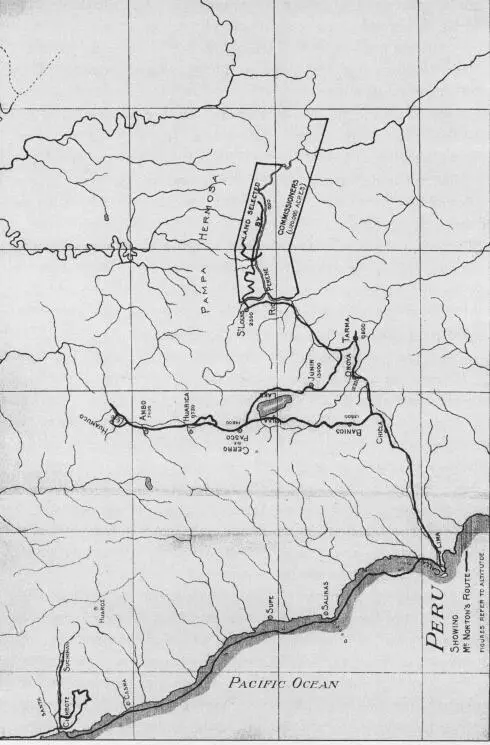

Marks was one story, but the other was more poignant. More personal. An early Kodak portable with a curious history. It was not the film that was missing, this time, but the camera. My great-grandfather, money dissipated through bad investments, property threatened — he moved south for the winter, from Aberdeen to the English Riviera, Paignton, I think, or Bournemouth — took off on what turned out to be a last, mad journey into the Peruvian interior. The tea interests he’d served so effectively in Ceylon wanted to know if this unmapped territory would be suitable for the cultivation of coffee. With a young man from the company, a small library of botanical books, odd volumes of De Quincey, quinine, salt, pen and ink, rifle and Kodak, he set out from Lima, through Chicla and Tarma, to the Rio Perene, towards land designated for potential exploitation by the commissioners.

Diaries and photographs and faithful camera were brought back by young Mr Stevenson, when the search for my great-grandfather was abandoned. A second expedition, funded by his widow, found nothing. The Indians retreated into the forest. A terse and unreliable account of the ill-omened river trip was assembled from unposted letters and journal extracts, which my great-grandfather had revised and polished during a month’s stay with a renegade Franciscan, in a district called Chanchamayo, while they waited for the weather to break — and for contact to be established with King Chokery, the Chuncho chief whose goodwill was required for any voyage on the upper reaches of the uncharted Perene.

The expedition, from the moment the ship sailed from Tilbury, was wrong, malfated. My great-grandfather, softened by the years of his retirement, missing wife and children, paced the deck, struggling for breath, feeling all of his fifty or so years. He was an abstemious man, he took a whisky or two with his dinner and a cigar with the first officer after it. His eyes were still sharp. They watched the stars.

The first officer, a stocky European with a literary beard and waxed moustache, quoted the painter Delacroix (as my great-grandfather noted in his journal): the light from the star Vega, hurtling through space, set out on its epic voyage twenty years before Monsieur Daguerre invented the process whereby its arrival in Cambridge could be recorded as a pin-sized impression on a metal plate. Something of the sort, so the merchant mariner suggested, should be applied to his conversation. To the tacit understanding that my great-grandfather would record his remarks. And that those insignificant blots on the page would, at some future epoch, be the source of unimaginable revelation.

Panama was a sink, Colon lived down to its name. The Scots Calvinist felt as if he were crawling into the continent by the back door: caecum to rectum, a yellow worm in a hunk of rotten meat.

Colon, our first landing port, apart from its luxurious vegetation, is a very wretched spot. It is only in a Spanish Republic that the existence of such a pestiferous place is possible. It is not merely the disreputable appearance of its degenerate people, nor the frequent squabbles dignified by the name of revolutions we have to fear, but the ever present filth, which is much more dangerous to life. Fortunately, a fire has recently burned down and purified a large portion of the town, rendering it, for a time, less dangerous to sojourners.

Driving east down the A13, past Creekmouth, with Jimmy Seed and the girls, the mess of the sewage outflow, filter beds, new retail parks, coned lanes, uncompleted ramps, I took the Peruvian journals as a literal guide: like for like. A shifting landscape of equivalents. The River Roding, disgorging in a septic scum into the Thames, became the Rio Perene. The man-made, conical alp of the Beckton ski slope stood in for the foothills of the Andes. Stacked container units in dirty primary colours hinted at the roll of film on which my great-grandfather made his survey of the missionary settlement in a jungle clearing.

The road was a villainous rut at a gradient of about one in three, a width of about eighteen inches, and knee deep in something like liquid glue. Before we had gone five miles one-half the cavalcade had come to grief, and it was some weeks ere we saw our pack mules again; indeed I believe some of them lie there still. We soon found out that the padres knew as little about the path as we did ourselves, and the upshot was we were benighted. Shortly after six o’clock we were overtaken in inky darkness, yet we plodded on, bespattered with mud, tired, bitten, and blistered by various insects. Whole boxes of matches were burned in enabling us to scramble over logs or avoid the deepest swamps. At last there was a slight opening in the forest, and the ruins of an old thatched shed were discovered, with one end of a broken beam resting upon an upright post, sufficient to shelter us from the heavy dews. It turned out to be the tomb of some old Inca chief whose bones have lain for over 350 years, and there, on the damp earth, we lay down beside them, just as we were. Our dinner consisted of a few sardines, which we ate, I shall not say greedily, for I felt tired and sulky, keeping a suspicious eye upon the Jesuit priests.

The Peruvian interior in the late nineteenth century, filtered through the prejudices of a weary Highlander of discounted Jacobite stock, a self-educated plantsman and jobbing author, was a more convincing mindscape than riverine, off-highway Essex. My great-grandfather’s notebooks were livelier than my own, more dyspeptic; he covered more ground (somebody found it worth their while to commission him to do so). The picaresque elements were the by-product of a very practical quest: could coffee be cultivated, cheaply, on this land? The Pampa Hermosa took precedence over the Dagenham Levels. Sepia photographs on wilting card, brought back by Mr Stevenson and spread across my desk, outranked my anaemic Polaroids. A ‘balsa’ on the Perene: loose-robed Indian with pole, great-grandfather squatting low to the water, rifle in lap, boy in prow watching out for submerged trees. The skeletal remains of a burnt-out Ford by the side of the road that led across Rainham Marshes to the landfill site. An orchid on the banks of the turbid stream, decadent, pale, carnivorous. Small blue flowers, soap-bleached, beside the Thames path, in the shadow of the Procter & Gamble factory at West Thurrock. Two of the wives of King Chokery. Jimmy’s postgraduate students, Track and Livia, posing beside an irrigation ditch.

Читать дальше