Again I was forcing the conversation. This was the kind of question with which doltish adults ply children. I used the word gadzhe for sweetheart, old-fashioned slang that had been current back in my teenage years.

Aba grinned.

‘Don’t people say gadzhe any more?!’

‘No, no, they still say it.’

‘So, do you have a gadzhe? ’

‘May I tell you a story?’

‘A real story?’

‘Yup.’

‘Go ahead.’

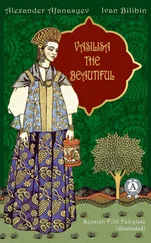

‘There is a Russian fairy tale in which the Tsar-maiden and Ivan, the merchant’s son, fall in love.’

‘The Tsar-maiden?’

‘Yes, that is what the story is called, ‘The Tsar-maiden’. So every time the two of them are supposed to meet, Ivan botches it by dropping off to sleep like a log. Ivan has this evil, jealous stepmother. She knows a trick: when she pricks Ivan’s clothes with a needle, he falls asleep. The Tsar-maiden is angry and returns to her empire, far away beyond seven hills, seven mountains, and…’

‘Seven seas!’

‘Ivan goes off after the maiden. He travels and travels, and finally reaches her, but not her heart. To reach her heart, Ivan still has to cross the sea. On the other shore grows an oak tree, in the oak there is a box, and in the box is a rabbit, and in the rabbit is a duck, and in the duck there is an egg. In that egg is hidden the love of the Tsar-maiden.’

‘And then?’

‘That is still not enough. The maiden must eat the egg. Once she eats it, the love for Ivan will return to her heart.’

‘So, does she eat this egg?’

‘She does. She is tricked into it, of course.’

‘Jesus! Who could walk that vast distance, then cross a sea, and then climb an oak. And then the egg! Hardboiled, no less? Ugh!’

‘Precisely. That is the whole point,’ said Aba, with a wry smile.

‘Now I know what this folklore of yours has taught you!’

‘What?’

‘High standards!’

We both burst into giggles. I liked the way she had packaged her answer. For the first time the conversation between us relaxed, and the whole situation acquired a rosy hue like a girl’s school excursion. Perhaps the unexpected weather contributed to this as well, perhaps it was I, not she, who had been tense to begin with, insisting on the rules of a ‘genre’ that I had defined in advance, and so forced her to adopt. Lord, she was so young! I tried to put myself in her shoes: yes, the ‘little girl’ had been adapting all the while to me, and truth be told, had been handling the situation with more style than I had. A girl’s school excursion, why not: when had I last had a chance to do something like this?! Perhaps I should stay on a day or two longer? After all, the ‘Golden Pen of the Balkans’ didn’t start for another few days.

‘And so. Tomorrow our story ends,’ she said, with a touch of irony.

The ‘our story’ rang like a shattered glass. She had used the Bulgarian phrase nashiyat s tebe roman . Russians say the same. The word roman can mean two things: the novel as a literary form, or a romantic liaison, an affair. The phrase to have a story with someone means to be in love. This was an awkward moment on her part: she had wanted to use a pun, she meant to use both meanings ironically, or maybe, who knows, had simply hoped to say something witty. I could understand all of that, the semantic overtones didn’t bother me. Something else was grating on my ear. That tone. Ding-ding-ding – dong! That tone.

* * *

It was the ring of hunger. I recognised that brand of hunger. She had a hunger for kindness that clung like a magnet to a kindred hunger for kindness and fed on it; a hunger for attention which attracted the same sort of hunger for attention; a blind hunger which sought to be led by the blind; a crippled hunger which sought an ally in the crippled, the hunger of a deaf mute cooing to a deaf mute.

Aba had stumbled onto the truth by chance: yes, she was an ageing little girl. She was born with the invisible mark of the unloved child on her brow. It made no difference whether they’d really loved her or not, would love her or not; the hunger was born with her, and with her it would vanish. There was little that could assuage that hunger; many had worn themselves ragged trying. Was it this, rather than genuine hunger, that punished mythical Erisychthon, who ended up gnawing at his own bones?

Aba found a common, secret language with my mother immediately. Perhaps they were made of the same stuff, and recognised each other without realising they had. They were bound by the same fear of vanishing, an unconscious desire to leave their mark behind them, to inscribe themselves on the map. They did not choose the means or the map in the process; it could have been the skin of their own children, the hand of a stranger. It was not their fault, nor was it anything they had done wrong. As if a capricious and thoughtless fairy had branded them at birth and made them think they were invisible. The sense that they were invisible acted on them like stomach acid and made them hungrier yet. There was nothing to assuage a hunger like that, not a giant magnifiying glass, or powerful spotlights, or the lavishing of attention. The hunger whimpered in their stomachs like a stray dog. This was a cunning hunger, gluttonous, capable of proudly refusing food, a sly foe able to hide and keep from being discovered, a tremulous foe who dared not raise a hand against itself, a lying and cheating foe, who knew how to make its whimpering sound like a siren song and left its saliva.

I looked at her. The kind face shaded with melancholy, which immediately provoked a feeling of guilt in the onlooker. She did everything she could to get others to like her. She loved her parents, if she had them, her friends, which she most certainly had. Because she was the one who never forgot a birthday, she was the one who sent courteous notes, postcards and emails, she was the one who was always first to pick up the phone and dial the number. She had never harmed anyone else; she had never kicked anyone in the shins; she never cheated in school; she was always a good pupil and a good student; she helped others; she never, or almost never, lied; she was kind to everyone; and in her bartering with emotions she always felt the loser. She watched me. She was interested in figuring out how the wheels and gears of my clock worked, and for the sake of discovery she was prepared to take the clock apart. Because why was it that everyone else in this world ticked and tocked so regularly, while only she was on the wrong beat?

I recognised the seductive whimper. I had been feeding my mother’s hunger for too long. After all, wasn’t I serving one of them here as a bedel , and the other as a potential morsel? Yes, love is on the distant shore of a wide sea. A large oak tree stands there, and in the tree there is a box, in the box a rabbit, in the rabbit a duck, and in the duck an egg. And the egg, in order to get the emotional mechanism going, had to be eaten.

The next morning dawned a quiet, grey day. I learned that the storm the night before had wreaked terrible damage, brought down electric lines, roofs had been ripped from houses, some of the local roads were blocked.

I kept to my decision to leave. The afternoon bus was going to go at four thirty.

‘You can stay if you like,’ I said, ‘and spend a few days with your cousin,’ I added cautiously.

‘No, we haven’t seen each other for years.’

She said it without pretence. There was no longer any point in pretending that she had come here to see her cousin.

‘I’m leaving. I’m going to see if I can find the street where my grandparents lived.’

‘I am going with you,’ she said. A childish determination rang in her voice.

Читать дальше