At dawn on the day following the festival of the New Year an armored tractor from Kibbutz Metsudat Ram began to plow a piece of land that had previously been worked illegally by the enemy. At first light the enemy artillery opened fire. The work continued, and the fire was not returned. The enemy proceeded to shell the civilian settlement indiscriminately with recoilless guns. The population took to the shelters. Our forces retaliated with heavy artillery fire. When approximately one-third of the disputed plot of land had been plowed, the tractor received a direct hit and its driver was killed. The engagement lasted some eighty minutes. Firing ceased only with the total silencing of the enemy positions, which sustained a large number of direct hits. With the exception of the tractor driver, our forces suffered no casualties. A member of Metsudat Ram, Misha Isarson, aged forty-four, was wounded in the arm by shrapnel. His wound was dressed on the spot, and he continued to discharge his duties as superintendent of the civil defense of the kibbutz. It is reported that during the shelling a member of the kibbutz died in his room. He was known to be ill at the time. Houses, farm buildings, and agricultural equipment suffered serious damage.

After the investigation and before the funeral, Ezra and Bronka, in agreement with Herbert Segal and others, decided to ask Siegfried to leave. Nobody suspected him and nobody blamed him, but we had received no clear explanation of the circumstances of his presence in Reuven Harish's room at the time of the tragedy. Noga's calm but insistent demand that he leave immediately tipped the balance against him.

The request was put to Siegfried Firmly but politely, and he responded with an indifference bordering on meekness. For pedagogic and other reasons Herbert Segal refused to allow him to see Noga. Siegfried replied that he understood and accepted Herbert's reasons. He offered Herbert a considerable sum of money for a library to be named in memory of Reuven Harish. When Herbert declined it, he burst into tears. He repeated the outburst when he took his leave of his brother and his family.

He left the country on a night flight. From the airport he sent a telegram to the secretary of Kibbutz Metsudat Ram expressing his gratitude and sympathy.

Siegfried left, and the rain came. Cruel drops. Monotonous complaint. Grumbling gutters. Dry dust turned to thick mud. Wet wind dashing against shuttered windows. Continuous howling of battered treetops.

On a dark, rainy morning Reuven Harish and the tractor driver, whose name was Mordecai Gelber, were laid to rest. Because of the rain there was only a short address. There was a symbolic link between the two deaths, as anyone with any sensitivity would appreciate, said Herbert Segal. Reuven Harish had been a pure man. We mourned his passing.

Three months passed.

Noga Harish was in the last three weeks of her pregnancy. On a stormy midwinter's day we saw her married to Avraham Rominov. There were no celebrations. Herbert Segal kissed both the orphans. Rami kissed Noga. Someone, Hasia or Nina or Gerda, perhaps all three, stifled a sob. Oren Geva scratched a pattern of wavy lines in the plaster on the wall with his fingernails. Ido Zohar took refuge in the empty recreation hall and composed a poem. Bronka made some curtains for the couple's room. Grisha dug a trench outside their window to carry off the rain water.

A fortnight went by. Gai Harish caught a cold. The good women looked after him. He was moved in the evening from the children's house to the Bergers' home. Bronka gave him tea with honey. Noga and Rami came to keep him company. Bronka stroked Noga's hair. Rami played checkers with the patient. Then he played chess with Ezra. Then the young couple left. Bronka turned the light out. In the night Gai's temperature went up, and next morning it came down again.

Gossip has informed us that Einav is pregnant again. Danny can crawl now. He plays with bricks. Tomer likes to throw his son up in the air and catch him in his big hands. Danny screams with joy. Einav screams with fear.

Ezra needs to wear glasses. In the evenings he reads aloud from the Bible in a cracked voice. Bronka sits facing him, knitting, listening or not listening.

Herbert Segal, in his room, puts a record on the record player and listens alone to the sound of the orchestra and the sounds of the wind and the rain. Sometimes he makes tea and mutters to himself, like many lonely people. Sometimes he gets out his violin and plays a simple tune or two.

What about Israel Tsitron, Herzl Goldring, Mendel Morag, Tsvi Ramigolski, Yitzhak Friedrich, and their wives, and the other members of the kibbutz? Now that it is winter and there is little work to be done they sleep a lot. Some of them read to broaden their minds. Some of them take part in study groups organized by the cultural committee. Others are content to withdraw into themselves. As we do, too, at merciful moments, when it does not gnaw at us or waft a cold deadness in our face.

The rain comes and goes. Dark clouds roll overhead and hurl themselves against the mountain wall. But they do not break it. The slopes sprout wild plants. Turbid water pours down the gulleys. The fishermen have removed their nets from the stormy lake. I am tired of the masquerade. I shall unmask. Perhaps, I, too, shall go to Abushdid's and huddle in a dark comer. Sip coffee and stare at the damp walls.

On the day of the spring festival Noga gave birth to her daughter. She named her Inbal, meaning the tongue of a bell. The baby was underweight, and her head was slightly flattened in the difficult delivery. Look at her face. Do all those other faces meet in it, Grandma Stella's, Eva's, Noga's, Siegfried's, Rami's, Ezra's, Reuven's? Her features are still unformed, though. True, she has blue eyes. But the color may well change in a few weeks' time.

The mountains are as in days gone by. I turn my eyes from them. I shall take my leave on a Friday night, at the Bergers' house. Outside the wind may howl and the rain beat down. The house is like a bell. Ezra is seated, wearing his glasses, which make him look old and resigned. Bronka and Noga confabulate in the cooking alcove. There is a warmth between them. Stella Maris. A paraffin heater bunts with a blue flame. On the rug, as always, are two babies. Dan and Inbal. Tomer and Rami discuss the news peacefully, amicably. Herbert Segal, who is visiting, drinks a glass of tea in silence, keeping his thoughts to himself. Einav drops off to sleep with a newspaper over her face. Gai and Oren are here, too, standing at Ezra's desk, heads together, dark hair touching fair hair, their joint stamp collection spread out in front of them.

The armchair in the corner is ringed with light. No one is sitting in it. Do not fill it with men and women who belong elsewhere. You must listen to the rain scratching at the windowpanes. You must look only at the people who are here, inside the warm room. You must see clearly. Remove every impediment. Absorb the different voices of the large family. Summon your strength. Perhaps close your eyes. And try to give this the name of love.

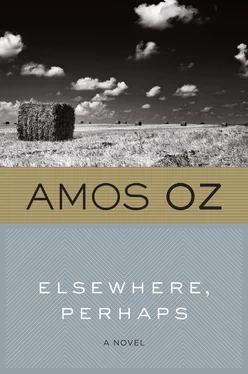

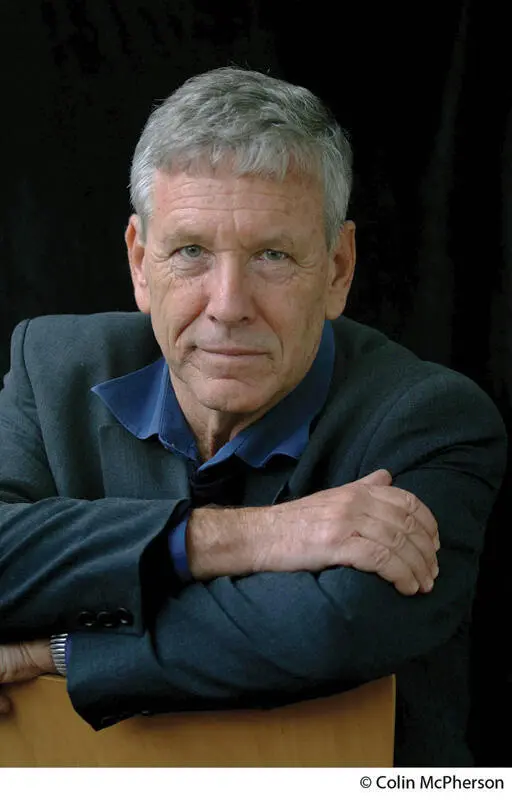

Born in Jerusalem in 1939, AMOS OZ is the author of numerous works of fiction and essays. His international awards include the Prix Femina, the Israel Prize, and the Frankfurt Peace Prize, and his books have been translated into more than thirty languages. He lives in Israel.

* English in original.

[back]

***

* English in original.

Читать дальше