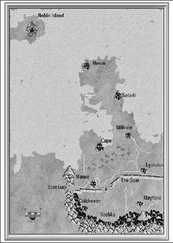

One after the other, the pair of them, Reuven from his window and Siegfried from his vantage point, saw two balls of fire blazing in the Camel's Field. One landed under the nose of the indifferent monster. The other whizzed past and shattered far away, at the edge of our vineyard. At once there was an answering whoosh. White lights flickered on the mountainside opposite. Now we unleashed our pent-up fury. A thick, dark column of smoke rose among the trenches and slanted northeastward, betraying the direction of the wind.

The tractor absent-mindedly, as though absorbed in philosophical speculation, continued on its course. Its pace neither increased nor slackened. It remained, as before, solemn and steady.

The firing grew faster and heavier. All around the armor-plated reptile bubbles of dazzling light burst, raising clouds of earth, smoke, and stones. Was the haughty machine protected by an invisible magic cordon?

Now that things were coming to a head, Reuven experienced a powerful surge of excitement. He felt a physical disturbance at the sight of the enemy shells falling wide of their target. The haughty indifference filled him with optimistic foreboding.

The world shattered into one great scream. A shell plunged into one of the fish ponds and raised a plume of muddy water. Another shell singled out the pine wood, smashed through the trees and blazed red black yellow orange. A third shell, quiveringly close, sliced off the roof of the tractor shed. A foul scorching smell assaulted Reuven Harish's nostrils. He leaned out of his window, held his head and vomited into the myrtles. He was still feeling happy. That powerful feverish flush that grips weak men when they suddenly have a ringside view of violent fighting. Let the struggle wage on to the utter end of its final destiny.

Reuven stood at his window, his mouth open wide to scream or to sing. But his innards rebeled and he vomited again and again. Herr Berger heard his retching. He came and stood on the other side of the myrtles. Calmly, politely, he asked whether he could be of assistance. A gun silenced the howling of the wind. Shells screamed here and in the enemy camp. The pine wood blazed with fire, and fire had taken the enemy's strongholds. Another fire raged in the tractor shed. A stench of burning rubber. The bloodcurdling bellow of a wounded cow.

Reuven Harish:

"Come in, my dear sir I have been waiting for you to come."

Siegfried, still calmly polite.

"I'm coming, I'm on my way, I'll be with you directly."

Columns of dust rose from tne slopes of the mountain. Dark men shot out of a dugout, running here and there with arms raised, like puppets whose strings have snapped.

A sound like a cord snapping close to the eardrum, followed by a menacing howl. The shell crashed into the wall of Fruma's house, the house that had been Fruma's in days gone by. The roof tilted, faltered, clung to the rafters with its fingernails, and finally gave in and collapsed with a hollow groan, raising a mushroom of dust.

Now from another point of view: the fire smoke howling sound and fury are mere illusion. Deception of unreliable senses. What is all the running of the tiny bouncing figures? What is their dark fear? The mountains stand as always.

At last an armor-piercing bullet penetrated the tractor's defenses and shattered its haughty pride. A blurred manikin shot out and zigzagged blindly across the field, falling and getting up, clasping his stomach, beating his chest with his fist as though swearing a powerful oath, leaping and flailing the air, as if the force of gravity had been momentarily weakened, caught his foot in a hole and collapsed on the ground, still kicking his legs in the air as though the whole universe had risen against him. Then, realizing the futility of kicking against empty space, he stretched his legs out, rested, made peace, lay still.

Reuven sits facing his visitor. A bowl of rosy-cheeked apples separates them. Slight disorder reigns in the room. The proper place for books is not on the floor. The packet of pills should have been put away in a drawer The sour smell of vomit is not pleasant to breathe.

Siegfried:

"I have come."

Reuven:

"So I see."

Siegfried:

"You're not well."

Reuven (why?):

"Thank you."

Siegfried:

"You're not cheerful."

Reuven:

"I'm ready."

Siegfried:

"Yes, you're ready. With your pure soul and your innocent mind you're ready for a Syrian shell to turn you into yet another Ramigolski, another plaster saint."

"My dear sir, try to tell me something new. Your cleverness has a rotten smell. You're playing the part of a grand-opera executioner. You're a dead man. I'm not afraid of you. So, you're laughing, Mr. Berger. But you're laughing at the wrong place. You're confused. That's not where you're supposed to laugh. Why did you laugh? Go and learn your part. You laughed in the wrong place."

"That's enough, Harismann. You have no strength left. You're tired out. Look at yourself. You're flushed. You're pale. No, don't look out of the window. You haven't got an alibi. You did flush. You did go pale. Your hand is shaking. You're all hunched up in your chair. You've lost her. You're ashamed to cry. You're holding back the tears. You're biting your lip. Don't deny it. You're gritting your teeth. Don't be ashamed. Cry. Let the tears flow. She's mine. You're mine. You're taking over the bank, but you've lost everything. That's not right, my dear pioneer, that's not the way for an honest man to behave. You want me to disappear. To be a bad dream. A nightmare. Feel me. Touch me. I'm not a ghost. I'm here, with you. In you. I'm real. I'm your humble servant. Your daughter's suitor. Your brother. Your best friend. Kiss my hand, Harismann. Beg for mercy. You're mine."

"Go away, sir, go away. Don't stay here."

"I'll take good care of her. I'll be gentle. I'll love her for you, too."

"Tell me, sir: she's beautiful, isn't she? Beautiful, quiet, dreamy — isn't she? She's… she's a miracle, sir. Isn't she?"

"Oh, how we love her, Harismann, you and I. In her we are one flesh. Why are you getting up? Sit down. Or rather lie down. Don't move. Movement now can be fatal. Lie still on the floor. Don't try to get up. It's dangerous. Lie still. Relax. Perfectly still. I'll fetch you some water. Here are your pills. No, you mustn't struggle. Relax, I said. Don't make any effort. Rest. It'll pass. The doctor's busy now with the wounded, but when it's all over he'll see you, too. I'm here by your side. You're not forsaken. You're in reliable hands. No, don't pull a face. Close your eyes. You're a good-looking man. High, clear brow. Don't be afraid. There's a friend at hand. Can you still hear me? A bosom friend. Don't move. Unclench your fist. Don't chew your lip, obstinate man. Take care. Be sensible. Don't put a strain on your heart. Stop gurgling like that. Here, I'll sit next to you. On the floor. Give me your hand. Pulse too fast. Perhaps I'll stroke your hair. I'll sing you a German song if you like. A lovely, sad children's song. I'll tell you an old story, too. Perhaps you'll go to sleep. Think of water. A little spring on the rocky mountainside. A stream trickling through the forest. An innocent little girl meets a wolf. Now a wide dark river. The water is cold, unchanging, gliding into the arms of the sea. Sea. Little waves. A dark jetty. White foam. A man and his daughter sailing together to the end of the sea. Go, pure man, go quietly, go in peace. Don't think about operatic executioners. Don't think darkness. Darkness is a tunnel from light to light. The transition is not difficult. Go to another place. Go across valleys and over mountains. See the roads that are forbidden to me. Who are you now, pure man. You're me when I was alive. I love you. I love you in your daughter. We were brothers. I loved you very much."

Читать дальше