If all the skies were parchment,

and all the seas were ink,

and all the feathers of all the birds were pens,

and all the men and all the women were scribes — even then

it would be impossible

to describe this marvel.

GAMALIEL

It was in La Verdad that I came across the book.

I’d flown down there from Canada for a mining conference and had just attended a meeting that finished around midday. My walk back to the hotel, along the Avenida del Sol, wasn’t too pleasant. July’s a steamy time of the year, especially in an inland city like La Verdad, built where there used to be nothing but jungle. The sidewalks were almost empty, for by this time of day even natives of the city look for shade. My northern body was unused to the sticky heat, making it all the worse.

The sky turned suddenly black and a drenching tropical downpour began. I ducked under the awning of a used bookstore I’d noticed on my way to the meeting. According to its stencilled, fly-by-night sign, it was called the Bookstore de Mexico. From the hybrid name, I thought it might have some books in English, though in the window I saw only worn-looking paperbacks with Spanish titles.

Since I couldn’t really go anywhere else till the lashing rain let up, I went through the open door for a look around.

No one else was in there except for an old Mayan woman in her traditional dress with its geometric patterns. She was sitting near the front at a table with a blue metal cash box on it. The store behind her was narrow, not much wider than a corridor, with warped, pressed-board bookcases along the walls and filling the space between. The only lighting came from some dangling electric bulbs without shades. A number of small lizards, as still as gargoyles, were clinging to the ceiling. In spite of everything, the smell of old books made the atmosphere not unpleasant.

As I strolled through, I could see that the books were indeed nearly all paperbacks. I glanced through the pages of a few of them, trying to figure out, from my smattering of Spanish, what they might be about. Some of the books were in poor condition and contained nests of silverfish. Others looked as though they’d been nibbled by rodents of one kind or another.

From experience, I handled them all gingerly. Years before, browsing through an old book in a store in northern Australia, I felt something soft moving under my fingers. I dropped the book and from it a scorpion the size of my hand scuttled away into the shadows.

I’D BEEN IN THE Bookstore de Mexico for maybe five minutes when I noticed the sky outside was lightening and the rain was letting up — it was now barely pattering down on the awning. I started to move towards the front door.

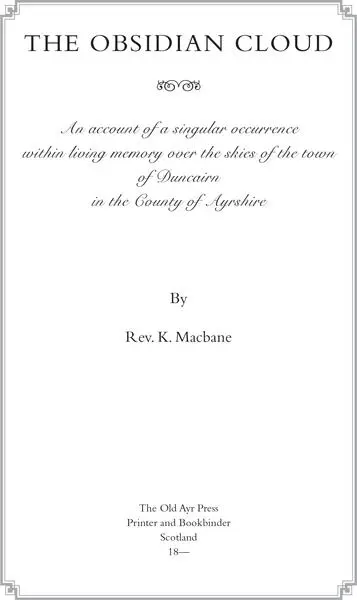

That was when I saw some hardcover books low on a shelf. One of them in particular caught my eye. It was a thin, oversized volume that didn’t fit properly amongst the other books, and it was lying flat on top of them. I leaned over for a closer look. It seemed to have an English title, so I lifted it out for a quick inspection.

The book gave off a musty smell. The print on the spine was of faded gold, so even close up all I could read was part of the title: The — dian Cloud . The cover was made of brown leather and the pages were so big and thick it was hard to separate them. There weren’t many of them — maybe a hundred, blotched with mildew and dampness. But I did manage to pry them apart at the title page:

Duncairn!

Seeing that name again so unexpectedly here, in another hemisphere, took my breath away. Duncairn was a little town in the Uplands of Scotland where I’d stayed for a brief time when I was a young man. Something had happened to me there that changed the whole trajectory of my life. It was a thing I’d never been able to forget. Or understand.

WITHOUT TRYING TO pry open any more of the pages of the old book, I took it over to the Mayan woman at her table. I wasn’t all that interested in what this “singular occurrence” might be that had taken place in Duncairn. But that familiar name made me want to have the book. I asked the woman for a price.

Her long hair, streaked with grey, was tied back. Her eyes were brown and unreadable.

“Dos mil pesos,” she said without blinking.

The price was ridiculous and probably meant for haggling over. But I paid her what she asked and she put the money in her metal box. She slid the book into a plastic bag and handed it to me in silence.

I thanked her for the shelter.

She nodded slightly, though I’m not sure she’d any idea what I’d said.

I LEFT THE Bookstore de Mexico and picked my way amongst the steaming puddles along the Avenida Del Sol. When I eventually got back to my hotel room, I settled down on the vinyl armchair with the book. Even the air conditioning couldn’t quite conquer the stink of mildew that arose from it. I lingered again over the title page, marvelling at the coincidence of seeing that name, Duncairn, and thinking back with a mixture of sadness and bitterness to my time there.

Then, carefully separating the thick, oversized pages, I began reading.

THE OBSIDIAN CLOUD seemed to be a factual account of what we’d nowadays call a “weather event.”

It began on a windy July morning. Just after ten o’clock, the wind shunted a wedge of low, dark clouds from over the North Sea onto the Scottish mainland. By the time the clouds reached the hills of the Southern Uplands, it was early afternoon and a particular grouping of them had melded together so smoothly that it had become just one very big cloud with a black underbelly.

At two o’clock, the wind died completely and the black cloud stalled directly over the high valley where the little town of Duncairn sits. The sky above the town, from hilltop to hilltop, north, south, east, and west, was so black and so smooth it resembled a mirror of polished obsidian, reflecting all the countryside beneath. Astonishingly, Duncairn itself was visible up there, with everything inverted: its streets and square, church and spire, surrounding fields and cottages, even the streams that would become the River Ayr worming their way down the hillsides and valleys.

Numerous reliable eyewitness accounts of the occurrence were given by those who lived in and around Duncairn, amongst them a greengrocer, the town clerk, a kiln operator, a tailor, a brewer, an apothecary’s assistant, the town constable, the lawyer, and even an itinerant dentist who was in the town on his quarterly visit. They all signed their names on affidavits.

The black cloud was so low-lying that some of those with acute eyesight swore they could make out their own tiny reflections up there, looking back down at them. “I could see my goodman rounding up the sheep in the east pasture,” the wife of a local farmer reported. “I could even see myself at the door of the cottage, and my cat Puddock sitting on my shoulder.”

Two lovers lying in a bracken-filled cranny high amongst the hills got quite a shock at seeing their activities reflected in the sky above them. They were willing to state what they’d seen but, understandably, since they were each married to someone else, asked not to be named.

One of the eyewitnesses, Dr. Thracy de Ware, a well-known naturalist and astronomer, added scientific weight to the testimony. He happened to be travelling in the Uplands that day, engaged in research. When the black mass approached overhead, he saw squadrons of panic-stricken birds darting for cover in the hedgerows and woodlots: they perched in the thousands in the boughs, motionless and silent. The mirroring effect of the cloud itself inspired de Ware to a rather poetic-sounding comment: “Through that vision I comprehended that our tiny, rotund earth, the merest particle in the great silent reel of the firmament, is also a garden of the most profound beauty.”

Читать дальше