I list my jobs, real and invented. Yes, yes, he cuts me off again, I’ve already read all that, he says and points at some printed sheets. Tell me something new, something I don’t know about you. I stare at him and try to think of an answer that will satisfy him. Something about me? I repeat. The spiky-haired guy screws up his eyes, lustful or conceited, as if I’ve insulted him, he starts fanning himself with a leaflet and says: Something, anything you like doing. I don’t know, I say quite honestly, and suddenly it comes to me: Dancing and running.

Good, good, he says, letting a smile escape, and he doesn’t know where to put his hands. As if they were superfluous. From then on he strikes me as a strange creature, one that inspires sympathy. I can’t look him in the eye any longer. On the desk is a frame with a family photo: him, the wife and three kids forming a human pyramid on the beach. And a magnetised desk-tidy full of paperclips and a little acrobat.

The thing is that there are two vacancies, one in the reptile house, the other in the children’s play area, he reveals quickly, as if trying to wrap things up. Any preference? I shrug. Well, if you haven’t heard within a week that you’ve definitely been picked, I’d advise you to keeping looking elsewhere. He says all this as he stands up, in a tone that makes no effort to disguise the fact that I have very little chance of being hired. He grips the handle and opens the door before I’ve even got to my feet. He doesn’t say goodbye so much as expel me. At the end of the corridor, before stepping outside, I think I hear a Good luck, very quiet, aborted by the sound of my footsteps; I add the final syllable myself.

The light of the sun at its zenith multiplies everything, endlessly. The asphalt steams; you can smell the soft tar. I cross the avenue and slip down a side street sheltered by enormous banana trees that manage to provide proper shade, a heat repellent. Halfway along the block, flanked by a series of narrow buildings, there’s an Adventist church. Three identical arches, a pretentious tower and a hand-painted sign.

ALCOHOLICS ANONYMOUS

TODAY ONLY

I turn my head and look the other way. Next to the kerb there’s a skip full of debris and rubbish. Shoe soles, springs, computer carcasses and books. Volumes of encyclopaedias, historical journals, leather spines and marbled bindings, most of them rotted away by humidity. A waste. I grab one at random: The Decameron . Underneath it, a picture of snakes is revealed. The words reptile house, spoken by the greasy man I’ve just seen, echo in my head. The coincidence prompts a quick, self-conspiratorial smile, as if I were standing with my double. A sign of destiny, an oversight of chance, it could be either.

It’s a heavy book, bound in hessian, difficult to handle. In a corner of the second page there’s an embossed stamp: Eduardo Ladislao Holmberg Library, it says in relief, framed by a plume and a knotted ribbon at the bottom. At the foot of the page, in black ink and italics, it says: NAT 351/II. I flick through the pages: snakes, lizards, tortoises, some rare plants and many other creatures. I think about Simón. I hesitate, I picture myself carrying this monster of a book the eight or nine blocks between here and the Fénix. I take it, in spite of its size, the fungus and fate.

Today I returned to work after four years. A bit more, a bit less, it doesn’t matter, just to make it a round number. All that time I had no serious, formal occupation, or even an informal one, no boss, no rotas, no wage. Without fully realising or feeling guilty about it, allowing the days and the countryside to lead me. There, people work without appearing to, either because they do nothing else or because they do nothing, quite the opposite of the city. I go back to work and in some part of me, through contagion, through defiance, I feel as stupid as I do proud, depending on the moment, generally more the former than the latter.

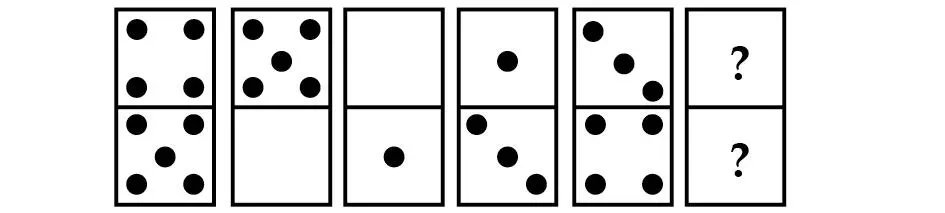

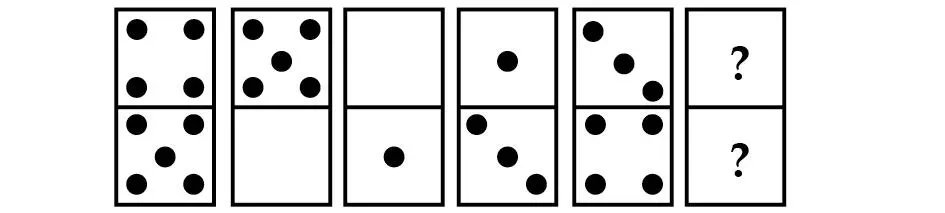

Despite the interview with the human resources man, I received another call from the zoo. This time it was to take psycho-physical tests. First they sent me to a clinic where they measured and weighed me, took a blood sample and an electrocardiogram. A few days later they summoned me to some offices in the centre of town. There, I was met by a girl quite a bit younger than me, probably a psychology student, who interviewed me for twenty minutes, subjecting me to questionnaires, illustrations and logic puzzles. She handed me a test with a hundred questions, beginning with: Do you feel that there aren’t enough hours in the day for all the things you need to do? I answer no to all of them and suspect that something must be wrong. There has to be a trick question somewhere. The girl flicks through it, nods in silence, exposing her lower lip, and says something she immediately regrets: Perfect score. She’s blabbed, rookie mistake. Instructions then follow to draw a house, a tree, a woman and a man, separately, on four blank sheets, and all together on a piece of blue card. Finally, a set of exercises with numbers and geometric shapes that make my eyes ache.

Now that I’m walking along beside the zoo railings, more than once I almost turn back, convinced this isn’t for me, things will sort themselves out, someone will provide for us. But I carry on, to everyone else’s rhythm; this is seemingly what I have to do. I try to picture what it will be like, the greetings, the introductions, the assignment of tasks. I’m out of the habit of dealing with other people, I imagine myself to be awkward, shy. A bit primitive.

I meet Iris at the main door first, for a relay operation. I go in, she comes out, Simón changes hands. The deal is that she’s going to take care of him while I’m working and in return I’ll cook for her at night. She doesn’t want anything else, don’t even mention money. I think about giving her some pointers but as soon as I open my mouth Iris frowns, annoyed in advance; she doesn’t like being told what to do. Simón eases the situation, I move away a few steps and he offers her his hand in a gesture of trust. Sometimes I feel I underestimate him, it must be because of his size, his laconic manner, everything that makes me believe he thinks less than he does. I’m mistaken. After saying goodbye, I spy on them over my shoulder. From a distance, despite the fact that they’re nothing like each other, not in their features or their gestures, even less in the colour of their hair, it would be perfectly natural to think they were mother and son. Iris’s ill-humoured face, her congenital bitterness, the kind that’s not so much an expression of something as a birthmark, anyone would associate with the tedium that some mothers feel no compulsion to conceal when taking their kids for a walk.

I present myself at the booth on República de la India ten minutes before the recommended time, as was suggested to me the last time I spoke to them. Staff entrance. I’m new, I’m starting today, I say. The security man shows his head at the window and for a moment I only have eyes for the fat, soft wart that lengthens his lip like a sleepy, sprawling beetle. The man comes out of his booth to better inspect me, a bloated guy, face like a boxer, with his golden canvas insignias on his shoulders and a badge that says Fortalezza , like that, with a double ‘z’ level with his right nipple. He communicates through his walkie-talkie with someone who speaks back in a broken, short-circuited robot voice. I can’t explain how, but the man understands everything that’s said and conveys the instructions to me. You have to pop into the human resources office to sign the contract, you know how to get there? I nod and give a quick Thanks. I’m welcomed by three camels living amid ruins. On the way to the administration building, I get a bit lost, twice I come out behind the toucan cage until finally I recognise a bower, the bridge and the lake.

Читать дальше