And then I tried to think about what I had to do, but I couldn’t think because there were too many other things in my head, so I did a maths problem to make my head clearer.

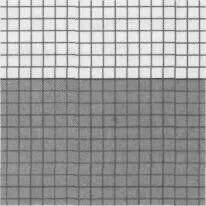

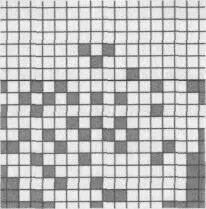

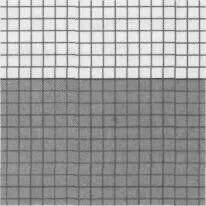

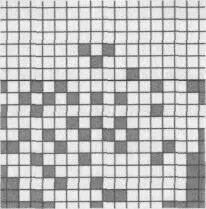

And the maths problem that I did was called Conway’s Soldiers.And in Conway’s Soldiersyou have a chessboard that continues infinitely in all directions and every square below a horizontal line has a colored tile on it like this:

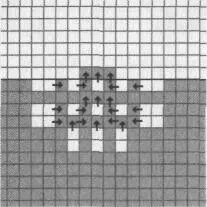

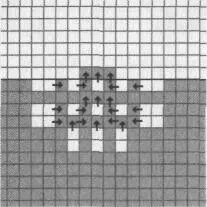

And you can move a colored tile only if it can jump over a colored tile horizontally or vertically (but not diagonally) into an empty square 2 squares away. And when you move a colored tile in this way you have to remove the colored tile that it jumped over, like this:

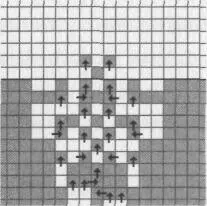

And you have to see how far you get the colored tiles above the starting horizontal line, and you start by doing something like this:

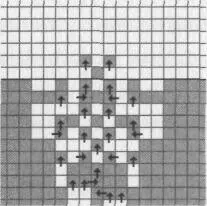

And then you do something like this:

And I know what the answer is because however you move the colored tiles you will never get a colored tile more than 4 squares above the starting horizontal line, but it is a good maths problem to do in your head when you don’t want to think about something else because you can make it as complicated as you need to fill your brain by making the board as big as you want and the moves as complicated as you want. And I had got to

and then I looked up and saw that there was a policeman standing in front of me and he was saying, “Anyone at home?” but I didn’t know what that meant.

And then he said, “Are you all right, young man?”

I looked at him and I thought for a bit so that I would answer the question correctly and I said, “No.”

And he said, “You’re looking a bit worse for wear.”

He had a gold ring on one of his fingers and it had curly letters on it but I couldn’t see what the letters were.

Then he said, “The lady at the cafe says you’ve been here for 2? hours, and when she tried talking to you, you were in a complete trance.”

Then he said, “What’s your name?”

And I said, “Christopher Boone.”

And he said, “Where do you live?”

And I said, “36 Randolph Street,” and I started feeling better because I like policemen and it was an easy question, and I wondered whether I should tell him that Father killed Wellington and whether he would arrest Father.

And he said, “What are you doing here?”

And I said, “I needed to sit down and be quiet and think.”

And he said, “OK, let’s keep it simple. What are you doing at the railway station?”

And I said, “I’m going to see Mother.”

And he said, “Mother?”

And I said, “Yes, Mother.”

And he said, “When’s your train?”

And I said, “I don’t know. She lives in London. I don’t know when there’s a train to London.”

And he said, “So, you don’t live with your mother?”

And I said, “No. But I’m going to.”

And then he sat down next to me and said, “So, where does your mother live?”

And I said, “In London.”

And he said, “Yes, but where in London?”

And I said, “451c Chapter Road, London NW2 5NG.”

And he said, “Jesus. What is that?”

And I looked down and I said, “That’s my pet rat, Toby,” because he was looking out of my pocket at the policeman.

And the policeman said, “A pet rat?”

And I said, “Yes, a pet rat. He’s very clean and he hasn’t got bubonic plague.”

And the policeman said, “Well that’s reassuring.”

And I said, “Yes.”

And he said, “Have you got a ticket?”

And I said, “No.”

And he said, “Have you got any money to get a ticket?”

And I said, “No.”

And he said, “So, how precisely were you going to get to London, then?”

And then I didn’t know what to say because I had Father’s cashpoint card in my pocket and it was illegal to steal things, but he was a policeman so I had to tell the truth, so I said, “I have a cashpoint card,” and I took it out of my pocket and I showed it to him. And this was a white lie.

But the policeman said, “Is this your card?”

And then I thought he might arrest me, and I said, “No, it’s Father’s.”

And he said, “Father’s?”

And I said, “Yes, Father’s.”

And he said, “OK,” but he said it really slowly and he squeezed his nose between his thumb and his forefinger.

And I said, “He told me the number,” which was another white lie.

And he said, “Why don’t you and I take a stroll to the cashpoint machine, eh?”

And I said, “You mustn’t touch me.”

And he said, “Why would I want to touch you?”

And I said, “I don’t know.”

And he said, “Well neither do I.”

And I said, “Because I got a caution for hitting a policeman, but I didn’t mean to hurt him and if I do it again I’ll get into even bigger trouble.”

Then he looked at me and he said, “You’re serious, aren’t you?”

And I said, “Yes.”

And he said, “You lead the way.”

And I said, “Where?”

And he said, “Back by the ticket office,”and he pointed with his thumb.

And then we walked back through the tunnel, but it wasn’t so frightening this time because there was a policeman with me.

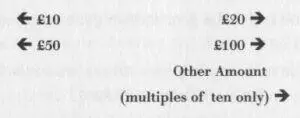

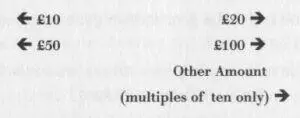

And I put the cashpoint card into the machine like Father had let me do sometimes when we were shopping together and it said ENTER YOUR PERSONAL NUMBERand I typed in 3558and pressed the ENTERbutton and the machine said PLEASE ENTER AMOUNTand there was a choice:

And I asked the policeman, “How much does it cost to get a ticket for a train to London?”

And he said, “About 30 quid.”

And I said, “Is that pounds?”

And he said, “Christ alive,” and he laughed. But I didn’t laugh because I don’t like people laughing at me, even if they are policemen. And he stopped laughing, and he said, “Yep. It’s 30 pounds.”

So I pressed ?50and five ?10 notes came out of the machine, and a receipt, and I put the notes and the receipt and the card into my pocket.

And the policeman said, “Well, I guess I shouldn’t keep you chatting any longer.”

And I said, “Where do I get a ticket for the train from?” because if you are lost and you need directions you can ask a policeman.

And he said, “You are a prize specimen, aren’t you?”

And I said, “Where do I get a ticket for the train from?” because he hadn’t answered my question.

And he said, “In there,” and he pointed and there was a big room with a glass window on the other side of the train station door, and then he said, “Now, are you sure you know what you’re doing?”

Читать дальше