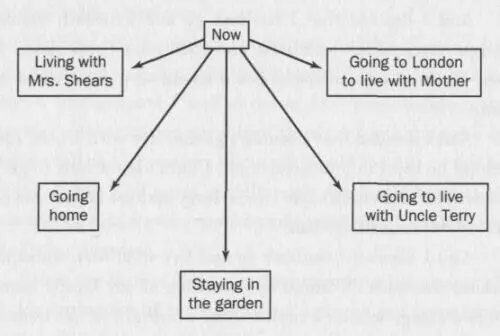

But then I thought about going home again, or staying where I was, or hiding in the garden every night and Father finding me, and that made me feel even more frightened. And when I thought about that I felt like I was going to be sick again like I did the night before.

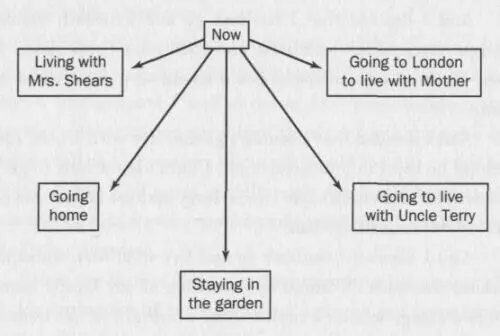

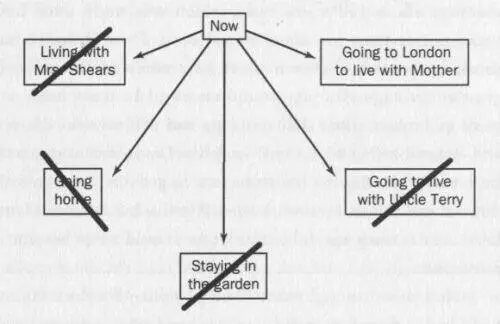

And then I realized that there was nothing I could do which felt safe. And I made a picture of it in my head like this:

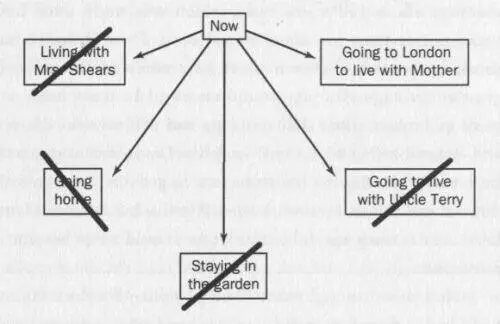

And then I imagined crossing out all the possibilities which were impossible, which is like in a maths exam when you look at all the questions and you decide which ones you are going to do and which ones you are not going to do and you cross out all the ones which you are not going to do because then your decision is final and you can’t change your mind. And it was like this:

Which meant that I had to go to London to live with Mother. And I could do it by going on a train because I knew all about trains from the train set, how you looked at the timetable and went to the station and bought a ticket and looked at the departure board to see if your train was on time and then you went to the right platform and got on board. And I would go from Swindon station, where Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson stop for lunch when they are on their way to Ross from Paddington in The Boscombe Valley Mystery.

And then I looked at the wall on the opposite side of the little passage down the side of Mrs. Shears’s house where I was sitting and there was the circular lid of a very old metal pan leaning against the wall. And it was covered in rust. And it looked like the surface of a planet because the rust was shaped like countries and continents and islands.

And then I thought how I could never be an astronaut because being an astronaut meant being hundreds of thousands of miles away from home, and my home was in London now and that was about 100 miles away, which was more than 1,000 times nearer than my home would be if I was in space, and thinking about this made me hurt. Like when I fell over in the grass at the edge of a playground once and I cut my knee on a piece of broken bottle that someone had thrown over the wall and I sliced a flap of skin off and Mr. Davis had to clean the flesh under the flap with disinfectant to get the germs and the dirt out and it hurt so much I cried. But this hurt was inside my head. And it made me sad to think that I could never become an astronaut.

And then I thought that I had to be like Sherlock Holmes and I had to detach my mind at will to a remarkable degree so that I did not notice how much it was hurting inside my head.

And then I thought I would need money if I was going to go to London. And I would need food to eat because it was a long journey and I wouldn’t know where to get food from. And then I thought I would need someone to look after Toby when I went to London because I couldn’t take him with me.

And then I Formulated a Plan. And that made me feel better because there was something in my head that had an order and a pattern and I just had to follow the instructions one after the other.

I stood up and I made sure there was no one in the street. Then I went to Mrs. Alexander’s house, which is next door to Mrs. Shears’s house, and I knocked on the door.

Then Mrs. Alexander opened the door, and she said, “Christopher, what on earth has happened to you?”

And I said, “Can you look after Toby for me?”

And she said, “Who’s Toby?”

And I said, “Toby’s my pet rat.”

Then Mrs. Alexander said, “Oh… Oh yes I remember now. You told me.”

Then I held Toby’s cage up and said, “This is him.” Mrs. Alexander took a step backward into her hallway. And I said, “He eats special pellets and you can buy them from a pet shop. But he can also eat biscuits and carrots and bread and chicken bones. But you mustn’t give him chocolate because it’s got caffeine and theobromine in it, which are methylxanthines, and it’s poisonous for rats in large quantities. And he needs new water in his bottle every day, too. And he won’t mind being in someone else’s house because he’s an animal. And he likes to come out of his cage, but it doesn’t matter if you don’t take him out.”

Then Mrs. Alexander said, “Why do you need someone to look after Toby, Christopher?”

And I said, “I’m going to London.”

And she said, “How long are you going for?”

And I said, “Until I go to university.”

And she said, “Can’t you take Toby with you?”

And I said, “London’s a long way away and I don’t want to take him on the train because I might lose him.”

And Mrs. Alexander said, “Right.” And then she said, “Are you and your father moving house?”

And I said, “No.”

And she said, “So, why are you going to London?”

And I said, “I’m going to live with Mother.”

And she said, “I thought you told me your mother was dead.”

And I said, “I thought she was dead, but she was still alive. And Father lied to me. And also he said he killed Wellington.”

And Mrs. Alexander said, “Oh, my goodness.”

And I said, “I’m going to live with my mother because Father killed Wellington and he lied and I’m frightened of being in the house with him.”

And Mrs. Alexander said, “Is your mother here?”

And I said, “No. Mother is in London.”

And she said, “So you’re going to London on your own?”

And I said, “Yes.”

And she said, “Look, Christopher, why don’t you come inside and sit down and we can talk about this and work out what is the best thing to do.”

And I said, “No. I can’t come inside. Will you look after Toby for me?”

And she said, “I really don’t think that would be a good idea, Christopher.”

And I didn’t say anything.

And she said, “Where’s your father at the moment, Christopher?”

And I said, “I don’t know.”

And she said, “Well, perhaps we should try and give him a ring and see if we can get in touch with him. I’m sure he’s worried about you. And I’m sure that there’s been some dreadful misunderstanding.”

So I turned round and I ran across the road back to our house. And I didn’t look before I crossed the road and a yellow Mini had to stop and the tires squealed on the road. And I ran down the side of the house and back through the garden gate and I bolted it behind me.

I tried to open the kitchen door but it was locked. So I picked up a brick that was lying on the ground and I smashed it through the window and the glass shattered everywhere. Then I put my arm through the broken glass and I opened the door from the inside.

I went into the house and I put Toby down on the kitchen table. Then I ran upstairs and I grabbed my schoolbag and I put some food for Toby in it and some of my maths books and some clean pants and a vest and a clean shirt. Then I came downstairs and I opened the fridge and I put a carton of orange juice into my bag, and a bottle of milk that hadn’t been opened. And I took two more Clementines and two tins of baked beans and a packet of custard creams from the cupboard and I put them in my bag as well, because I could open them with the can opener or my Swiss Army knife.

Then I looked on the surface next to the sink and I saw Father’s mobile phone and his wallet and his address book and I felt my skin… cold under my clothes like Doctor Watson in The Sign of Four when he sees the tiny footsteps of Tonga, the Andaman Islander, on the roof of Bartholomew Sholto’s house in Norwood, because I thought Father had come back and he was in the house, and the pain in my head got much worse. But then I rewound the pictures in my memory and I saw that his van wasn’t parked outside the house, so he must have left his mobile phone and his wallet and his address book when he left the house. And I picked up his wallet and I took his bank card out because that was how I could get money because the card has a PIN which is the secret code which you put into the machine at the bank to get money out and Father hadn’t written it down in a safe place, which is what you’re meant to do, but he had told me because he said I’d never forget it. And it was 3558. And I put the card into my pocket.

Читать дальше