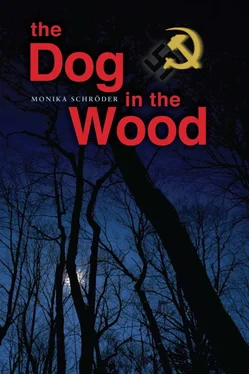

Monika Schröder

THE DOG IN THE WOOD

In the distance Fritz heard again the droning of engines. The front was coming closer, and the east wind blew the noise of cannons, tanks, and gunfire toward their farm. The Russians would be there soon. Fritz set down the tray with the tomato seedlings on the corner post of the garden fence and looked up into the cloudless sky. No sign of the Luftwaffe. The Russians should have come during the winter when the weather was gloomy and everyone had to stay inside. Now, in late April, Fritz enjoyed being outside and the best time for gardening had begun. The garden was at the south end of the farm, behind the barn, overlooking the pond and the family’s forest in the distance. Fritz imagined the Russians coming through the forest. Would they arrive in tanks? Would there be air raids? He had seen a picture of a Russian soldier in a leaflet about Bolshevism on Grandpa’s desk. A man with a shorn head and mean eyes, holding a knife between his teeth, was running after a blond child. Fritz squatted down and began his work. Better not to think about what would happen when the Russians arrived. He loosened the fragile tomato seedlings from their pots and set them one by one into the row of small hollows he had prepared in the soil. By the time the tomatoes were ripe the war would be long over.

Grandpa still believed in the German victory. But fewer and fewer people seemed to share his conviction. In recent weeks, most villagers had gone back to saying simply “Good Day” when they met Grandfather on the street instead of returning his “Heil Hitler” greeting. Grandpa owned the largest farm in the village. At the main entrance a sign in bold letters under a swastika announced him as the head of the local Nazi Party Farmers’ Association.

Last weekend, as Fritz had helped Oma Lou pluck feathers off a chicken, Grandpa had come home from a meeting in his uniform and thrown his hat on the coat rack, entering the kitchen with his big ears flaming red.

“What’s the matter, Karl?” Oma Lou had asked, looking up. “Why are you upset?”

“People are showing their real colors. The end is near,” Grandfather had answered. “They are beginning to hang their coats in the new wind.”

Fritz had imagined all the neighbors in colorful new coats, taking them off and letting them blow in the wind. But the worried expression on Oma Lou’s face had told him he had misunderstood his grandfather’s comment, and he had been left wondering what it meant.

Grandpa thought that gardening was women’s work, but Fritz loved to care for Oma Lou’s large garden. He had germinated these tomatoes and put them into small earthen pots on the windowsill in the hallway. Now that the small plants had each grown at least five leaves, they were ready to be planted in the garden. Tomatoes need sunshine, and here, along the fence at the south end of the garden, they would be fully exposed to the afternoon light.

“Don’t waste your time with tomatoes, boy!” Grandpa’s voice suddenly boomed from the other side of the fence. “Come with me!”

Fritz still needed to water the plants, but Grandpa was already striding back to the house. Fritz hurried to follow Grandpa’s orders. He shook the dirt off his pants and left the garden tools at the side of the fence, wondering which chore Grandpa would assign him now. When he entered the yard, Grandpa had taken his seat on the horse cart and was motioning Fritz to climb up next to him.

“Where are we going?” Fritz asked as Grandpa stirred the horses toward the forest.

“I want to show you something,” Grandpa replied. The edge of the woods grew closer, and when they reached the low fir trees marking the entrance to the family’s forest, Grandpa stopped the horses and stepped down from the seat of the cart. “We’ll leave the horses here and walk the last part.”

Fritz jumped off and followed Grandpa into the woods.

“Come on, boy!” Grandpa called now, and hurried briskly through the underbrush. Fritz had to rush to follow Grandpa’s long stride. Grandpa’s presence seemed to leave less space in his chest to breathe. He was panting when Grandpa finally stopped in front of a large pine tree. Several cut branches were spread out flat under the tree. Grandpa bent down to move one of the branches aside. A large rectangular hole, about five feet deep, came into view. Fresh soil was piled up behind the tree trunk. “Did you dig this hole?” Fritz looked into the dugout. The old man nodded. “What is it for?” A large vein was throbbing on Grandpa’s neck. Fritz had seen the throbbing vein before. It seemed to bulge before Grandpa broke out into a fit of rage. A quick surge of guilt shot through Fritz, but he didn’t have enough time to search his mind for what he might be guilty of.

“This will be the hideout for your mother, your grandmother, and your sister when the Russians reach our village.” Fritz imagined Mama; his sister, Irmi; and Oma Lou huddled inside the hole while Russian soldiers searched the forest.

“Now see if there is enough space for three people.” Grandpa took the rope he had brought, tied one end around the tree beside the hole, and passed Fritz the other end. Fritz, still taken by the image of the women hidden in the hole while Russians were shooting from behind trees, just stared. He wanted to ask why space for just three people was all that was needed, but his throat was too tight to speak. Grandpa nudged him to climb down into the hole. Reluctantly, he lowered himself along the rope into the opening.

“You and I will defend our land against the Bolshevik enemy,” Grandpa declared as if he had read Fritz’s mind. Fritz shuddered in the cool dampness that surrounded him. How could the two of them defend their farm against the approaching Russian army? Fritz had turned ten only last month. He pictured himself with a large rifle standing beside Grandpa, firing against the approaching enemy soldiers. The Russians were supposed to be fierce and cruel fighters. Fritz took hold of the rope, looking up to see if he had permission to climb back up again.

“I want you to know where to find the women in case something happens to me,” Grandpa called down. “This pine tree will be your landmark. It’s easy to recognize. It’s taller than the others, and its trunk splits into two arms. You see?” Grandpa pointed toward the treetop. “It looks like a fork.” Fritz followed Grandpa’s arm, still trying to make sense of what he had just heard. Down in the hole Fritz felt even smaller and weaker than when he stood beside Grandpa. What did Grandpa mean when he said “if something happens to me…”? Was Grandpa expecting to die in the fight for the village?

“What about Lech?” Fritz dared to ask, but his voice came out like a croak. If they had to fight, Fritz wanted to be close to Lech.

“That Polack will probably run away soon. The two French laborers at the Bartels’ farm ran away last week, taking a horse with them. You don’t need to worry about the Pole once the Russians come.” Grandpa dismissed Fritz’s worry with a quick movement of his hand, throwing a birdlike shadow over the hole.

“But he has worked for us for a long time. Couldn’t he help us?” The words came out more softly than Fritz had wanted.

“These forced laborers didn’t come here because they wanted to work for us. We made them come here.” Grandpa stepped close to the hole. The tip of his left boot loomed over the rim.

“Stomp down the soil for a floor,” Grandpa ordered before Fritz could ask how he was so sure that Lech wanted to run away. Lech was tall and strong, and he could be helpful defending the farm. Small rivulets of sandy soil slid down the sides while Fritz tamped the ground with his shoes. “Tomorrow we’ll bring some boards to hold up the sides and to protect the hole from rain.”

Читать дальше