‘So he got away with it,’ I repeated.

‘Depends on how you describe got away with it,’ said Mick, ‘because although the police never charged Pete, the copper in charge of the case later made a statement saying that they’d closed their inquiries, as there was no one else they wanted to interview — hint, hint. That wasn’t what you call a good career move for Chambers and Davis, so they set about stitching Pete up.’

‘But Pete only had six weeks to serve before he was due to be released,’ I reminded Mick, ‘and he was always as good as gold.’

‘True, but another screw, a mate of Davis’s, reported Pete for stealing a pair of jeans from the stores just a few days before he was due for release. Pete was carted off to segregation and the governor had him transported back to Lincoln nick even before they’d served up tea that night, with another three months added to his sentence.’

‘So he ended up having to serve another three months?’

‘That was six years ago,’ said Mick. ‘And Pete’s still banged up in Lincoln.’

‘So how do they manage that?’

‘The screws just come up with a new charge every few weeks, so that whenever Pete comes up on report the governor adds another three months to his sentence. My bet is Pete’s stuck in Lincoln for the rest of his life. What a liberty.’

‘But how do they get away with it?’ I asked.

‘Haven’t you been listening to anything I’ve been saying, Jeff? If two screws say that’s what happened, then that’s what happened,’ repeated Mick, ‘and no con will be able to tell you any different. Understood?’

‘Understood,’ I replied.

On 12 September 2002 Prison Service Instruction No. 47/2002 stated that the judgement of the European Court of Human Rights in the case of Ezeh & Connors ruled that, where an offence was so extreme as to result in a punishment of additional days, the protections inherent in Article 6 of the European Convention of Human Rights applied. A hearing must be conducted by an independent and impartial tribunal, and prisoners are entitled to legal assistance at such hearings.

Pete Bailey was released from Lincoln prison on 19 October 2002.

George Tsakiris is not one of those Greeks you need to beware of when he is bearing gifts.

George is fortunate enough to spend half his life in London and the other half in his native Athens. He and his two younger brothers, Nicholas and Andrew, run between them a highly successful salvage company, which they inherited from their father.

George and I first met many years ago during a charity function in aid of the Red Cross. His wife Christina was a member of the organizing committee, and she had invited me to be the auctioneer.

At almost every charity auction I have conducted over the years, there has been one item for which you just can’t find a buyer, and that night was no exception. On this occasion, another member of the committee had donated a landscape painting that had been daubed by their daughter and would have been orphaned at a village fete. I felt, long before I climbed up onto the rostrum and searched around the room for an opening bid, that I was going to be left stranded once again.

However, I had not taken George’s generosity into consideration.

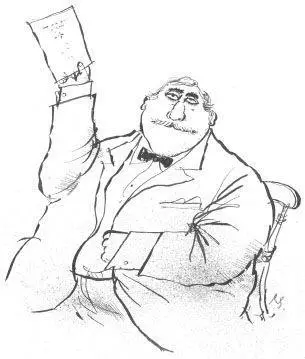

‘Do I have an opening bid of one thousand pounds?’ I enquired hopefully, but no one came to my rescue. ‘One thousand?’ I repeated, trying not to sound desperate, and just as I was about to give up, out of a sea of black dinner jackets a hand was raised. It was George’s.

‘Two thousand,’ I suggested, but no one was interested in my suggestion. ‘Three thousand,’ I said looking directly at George. Once again his hand shot up. ‘Four thousand,’ I declared confidently, but my confidence was short-lived, so I returned my attention to George. ‘Five thousand,’ I demanded, and once again he obliged. Despite his wife being on the committee, I felt enough was enough. ‘Sold for five thousand pounds, to Mr George Tsakiris,’ I announced to loud applause, and a look of relief on Christina’s face.

Since then poor George, or to be more accurate rich George, has regularly come to my rescue at such functions, often purchasing ridiculous items, for which I had no hope of arousing even an opening bid. Heaven knows how much I’ve prised out of the man over the years, all in the name of charity.

Last year, after I’d sold him a trip to Uzbekistan, plus two economy tickets courtesy of Aeroflot, I made my way across to his table to thank him for his generosity.

‘No need to thank me,’ George said as I sat down beside him. ‘Not a day goes by without me realizing how fortunate I’ve been, even how lucky I am to be alive.’

‘Lucky to be alive?’ I said, smelling a story.

Let me say at this point that the tired old cliché, that there’s a book in every one of us, is a fallacy. However, I have come to accept over the years that most people have experienced a single incident in their life that is unique to them, and well worthy of a short story. George was no exception.

‘Lucky to be alive,’ I repeated.

George and his two brothers divide their business responsibilities equally: George runs the London office, while Nicholas remains in Athens, which allows Andrew to roam around the globe whenever one of their sinking clients needs to be kept afloat.

Although George maintains establishments in London, New York and Saint-Paul-de-Vence, he still regularly returns to the home of the gods, so that he can keep in touch with his large family. Have you noticed how wealthy people always seem to have large families?

At a recent Red Cross Ball, held at the Dorchester, no one came to my rescue when I offered a British Lions’ rugby shirt — following their tour of New Zealand — that had been signed by the entire losing team. George was nowhere to be seen, as he’d returned to his native land to attend the wedding of a favourite niece. If it hadn’t been for an incident that took place at that wedding, I would never have seen George again. Incidentally, I failed to get even an opening bid for the British Lions’ shirt.

George’s niece, Isabella, was a native of Cephalonia, one of the most beautiful of the Greek islands, set like a magnificent jewel in the Ionian Sea. Isabella had fallen in love with the son of a local wine grower, and as her father was no longer alive, George had offered to host the wedding reception, which was to be held at the bridegroom’s home.

In England it is the custom to invite family and friends to attend the wedding service, followed by a reception, which is often held in a marquee on the lawn of the home of the daughter’s parents. When the lawn is not large enough, the festivities are moved to the village hall. After the formal speeches have been delivered, and a reasonable period of time has elapsed, the bride and groom depart for their honeymoon, and fairly soon afterwards the guests make their way home.

Leaving a party before midnight is not a tradition the Greeks have come to terms with. They assume that any festivities after a wedding will continue long into the early hours of the following morning, especially when the bridegroom owns a vineyard. Whenever two natives are married on a Greek island, an invitation is automatically extended to the locals so that they can share in a glass of wine and toast the bride’s health. Wedding crasher is not an expression that the Greeks are familiar with. The bride’s mother doesn’t bother sending out gold-embossed cards with RSVP in the lower left-hand corner for one simple reason: no one would bother to reply, but everyone would still turn up.

Читать дальше