‘Good morning, Mr Adams,’ said Pat.

‘When I looked at the list of defendants this morning, Pat, and saw your name,’ said Mr Adams, I assumed it must be that time of the year when you make your annual appearance. Follow me, Pat, and let’s get this over with as quickly as possible.’

Pat accompanied Mr Adams through the back door of the courthouse and on down the long corridor to a holding cell.

Thank you, Mr Adams,’ said Pat as he took a seat on a thin wooden bench that was cemented to a wall along one side of the large oblong room. If you’d be kind enough to just leave me for a few moments,’ Pat added, ‘so that I can compose myself before the curtain goes up.’

Mr Adams smiled, and turned to leave.

‘By the way,’ said Pat, as Mr Adams touched the handle of the door, ‘did I tell you about the time I tried to get a labouring job on a building site in Liverpool, but the foreman, a bloody Englishman, had the nerve to ask me—’

‘Sorry, Pat, some of us have got a job to do, and in any case, you told me that story last October.’ He paused. ‘And, come to think of it, the October before.’

Pat sat silently on the bench and, as he had nothing else to read, considered the graffiti on the wall. Perkins is a prat. He felt able to agree with that sentiment. Man U are the champions. Someone had crossed out Man U and replaced it with Chelsea. Pat wondered if he should cross out Chelsea, and write in Cork, whom neither team had ever defeated. As there was no clock on the wall, Pat couldn’t be sure how much time had passed before Mr Adams finally returned to escort him up to the courtroom. Adams was now dressed in a long black gown, looking like Pat’s old headmaster.

‘Follow me,’ Mr Adams intoned solemnly.

Pat remained unusually silent as they proceeded down the yellow brick road, as the old lags call the last few yards before you climb the steps and enter the back door of the court. Pat ended up standing in the dock, with a bailiff by his side.

Pat stared up at the bench and looked at the three magistrates who made up this morning’s panel. Something was wrong. He had been expecting to see Mr Perkins, who had been bald this time last year, almost Pickwickian. Now, suddenly, he seemed to have sprouted a head of fair hair. On his right was Councillor Steadman, a liberal, who was much too lenient for Pat’s liking. On the chairman’s left sat a middle-aged lady whom Pat had never seen before; her thin lips and piggy eyes gave Pat a little confidence that the liberal could be outvoted two to one, especially if he played his cards right. Miss Piggy looked as if she would have happily supported capital punishment for shoplifters.

Sergeant Webster stepped into the witness box and took the oath.

‘What can you tell us about this case, Sergeant?’ Mr Perkins asked, once the oath had been administered.

‘May I refer to my notes, your honour?’ asked Sergeant Webster, turning to face the chairman of the panel. Mr Perkins nodded, and the sergeant turned over the cover of his notepad.

‘I apprehended the defendant at two o’clock this morning, after he had thrown a brick at the window of H. Samuel, the jeweller’s, on Mason Street.’

‘Did you see him throw the brick, Sergeant?’

‘No, I did not,’ admitted Webster, ‘but he was standing on the pavement with the brick in his hand when I apprehended him.’

‘And had he managed to gain entry?’ asked Perkins.

‘No, sir,’ said the sergeant, ‘but he was about to throw the brick again when I arrested him.’

‘The same brick?’

‘I think so.’

‘And had he done any damage?’

‘He had shattered the glass, but a security grille prevented him from removing anything.’

‘How valuable were the goods in the window?’ asked Mr Perkins.

‘There were no goods in the window,’ replied the sergeant, ‘because the manager always locks them up in the safe, before going home at night.’

Mr Perkins looked puzzled and, glancing down at the charge sheet, said, ‘I see you have charged O’Flynn with attempting to break and enter.’

‘That is correct, sir,’ said Sergeant Webster, returning his notebook to a back pocket of his trousers.

Mr Perkins turned his attention to Pat. ‘I note that you have entered a plea of guilty on the charge sheet, O’Flynn.’

‘Yes, m’lord.’

‘Then I’ll have to sentence you to three months, unless you can offer some explanation.’ He paused and looked down at Pat over the top of his half-moon spectacles. ‘Do you wish to make a statement?’ he asked.

‘Three months is not enough, m’lord.’

‘I am not a lord,’ said Mr Perkins firmly.

‘Oh, aren’t you?’ said Pat. ‘It’s just that I thought as you were wearing a wig, which you didn’t have this time last year, you must be a lord.’

‘Watch your tongue,’ said Mr Perkins, ‘or I may have to consider putting your sentence up to six months.’

‘That’s more like it, m’lord,’ said Pat.

‘If that’s more like it,’ said Mr Perkins, barely able to control his temper, ‘then I sentence you to six months. Take the prisoner down.’

‘Thank you, m’lord,’ said Pat, and added under his breath, ‘see you this time next year.’

The bailiff hustled Pat out of the dock and quickly down the stairs to the basement.

‘Nice one, Pat,’ he said before locking him back up in a holding cell.

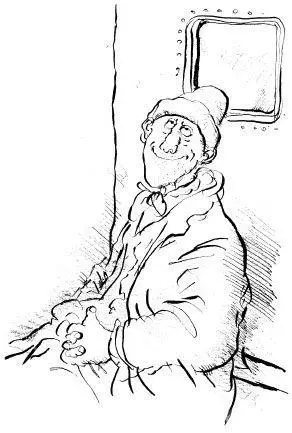

Pat remained in the holding cell while he waited for all the necessary forms to be filled in. Several hours passed before the cell door was finally opened and he was escorted out of the courthouse to his waiting transport; not on this occasion a panda car driven by Sergeant Webster, but a long blue-and-white van with a dozen tiny cubicles inside, known as the sweat box.

‘Where are they taking me this time?’ Pat asked a not very communicative officer whom he’d never seen before.

‘You’ll find out when you get there, Paddy,’ was all he got in reply.

‘Have I ever told you about the time I tried to get a job on a building site in Liverpool?’

‘No,’ replied the officer, ‘and I don’t want to ’ear—’

‘—and the foreman, a bloody Englishman, had the nerve to ask me if I knew the difference between a—’ Pat was shoved up the steps of the van and pushed into a little cubicle that resembled a lavatory on a plane. He fell onto the plastic seat as the door was slammed behind him.

Pat stared out of the tiny square window, and when the vehicle turned south onto Baker Street, realized it had to be Belmarsh. Pat sighed. At least they’ve got a half-decent library, he thought, and I may even be able to get back my old job in the kitchen.

When the Black Maria pulled up outside the prison gates, his guess was confirmed. A large green board attached to the prison gate announced BELMARSH, and some wag had replaced BEL with HELL. The van proceeded through one set of double-barred gates, and then another, before finally coming to a halt in a barren yard.

Twelve prisoners were herded out of the van and marched up the steps to an induction area, where they waited in line. Pat smiled when he reached the front of the queue and saw who was behind the desk, checking them all in.

‘And how are we this fine pleasant evening, Mr Jenkins?’ Pat asked.

The Senior Officer looked up from behind his desk and said, ‘It can’t be October already.’

Читать дальше