Mr Cartwright estimated that nearly three hundred and fifty customers passed through the restaurant during the evening, and if you added that to the lunchtime clientele, the total came to just over five hundred a day. He also calculated that around half of them were paying cash, but he still had no way of proving it.

Dennis’s dinner bill came to £75 (it’s fascinating how restaurants appear to charge more in the evening than they do for lunch, even when they serve exactly the same food). Mr Cartwright estimated that each customer was being charged between £25 and £40, and that was probably on the conservative side. So in any given week, Mario had to be serving at least three thousand customers, returning him an income of around £90,000 a week, which was in excess of four million pounds a year, even if you discounted the month of August.

When Mr Cartwright returned to his office the following morning, he once again went over the restaurant’s books. Mr Gambotti was declaring a turnover of £2,120,000, and showing, after outgoings, a profit of £172,000. So what was happening to the other two million?

Mr Cartwright remained baffled. He took the ledgers home in the evening, and continued to study the figures long into the night.

‘Eureka,’ he declared just before putting on his pyjamas. One of the outgoings didn’t add up. The following morning he made an appointment to see his supervisor. ‘I’ll need to get my hands on the details of these particular weekly numbers,’ Dennis told Mr Buchanan, as he placed a forefinger on one of the items listed under outgoings, ‘and more important,’ he added, ‘without Mr Gambotti realizing what I’m up to.’ Mr Buchanan sanctioned a request for him to be out of the office, as long as it didn’t require any further visits to Mario’s.

Mr Cartwright spent most of the weekend refining his plan, aware that just the slightest hint of what he was up to would allow Mr Gambotti enough time to cover his tracks.

On Monday Mr Cartwright rose early and drove to Fulham, not bothering to check in at the office. He parked his Skoda down a side street that allowed him a clear view of the entrance to Mario’s restaurant. He removed a notebook from an inside pocket and began to write down the names of every tradesman who visited the premises that morning.

The first van to arrive and park on the double yellow line outside the restaurant’s front door was a well-known purveyor of vegetables, followed a few minutes later by a master butcher. Next to unload her wares was a fashionable florist, followed by a wine merchant, a fishmonger and finally the one vehicle Mr Cartwright had been waiting for — a laundry van. Once the driver had unloaded three large crates, dumped them inside the restaurant and come back out, lugging three more crates, he drove away. Mr Cartwright didn’t need to follow the van as the company’s name, address and telephone number were emblazoned across both sides of the vehicle.

Mr Cartwright returned to the office, and was seated behind his desk just before midday. He reported immediately to his supervisor, and sought his authority to make a spot-check on the company concerned. Mr Buchanan again sanctioned his request, but on this occasion recommended caution. He advised Cartwright to carry out a routine enquiry, so that the company concerned would not work out what he was really looking for. ‘It may take a little longer,’ Buchanan added, ‘but it will give us a far better chance of success in the long run. I’ll drop them a line today, and then you can fix up a meeting, at their convenience.’

Dennis went along with his supervisor’s suggestion, which meant that he didn’t turn up at the offices of the Marco Polo laundry company for another three weeks. On arrival at the laundry, by appointment, he made it clear to the manager that his visit was nothing more than a routine check, and he wasn’t expecting to find any irregularities.

Dennis spent the rest of the day checking through every one of their customers’ accounts, only stopping to make detailed notes whenever he came across an entry for Mario’s restaurant. By midday he had gathered all the evidence he needed, but he didn’t leave Marco Polo’s offices until five, so that no one would become suspicious. When Dennis departed for the day, he assured the manager that he was well satisfied with their bookkeeping, and there would be no follow-up. What he didn’t tell him was that one of their most important customers would be followed up.

Mr Cartwright was seated at his desk by eight o’clock the following morning, making sure his report was completed before his boss appeared.

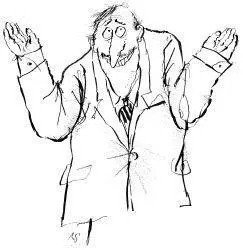

When Mr Buchanan walked in at five to nine, Dennis leapt up from behind his desk, a look of triumph on his face. He was just about to pass on his news, when the supervisor placed a finger to his lips and indicated that he should follow him through to his office. Once the door was closed, Dennis placed the report on the table and took his boss through the details of his enquiries. He waited patiently while Mr Buchanan studied the documents and considered their implications. He finally looked up, to indicate that Dennis could now speak.

‘This shows,’ Dennis began, ‘that every day for the past twelve months Mr Gambotti has sent out two hundred tablecloths and over five hundred napkins to the Marco Polo laundry. If you then look at this particular entry,’ he added, pointing to an open ledger on the other side of the desk, ‘you will observe that Gambotti is only declaring a hundred and twenty bookings a day, for around three hundred customers.’ Dennis paused before delivering his accountant’s coup de grâce. ‘Why would you need a further three thousand tablecloths and forty-five thousand napkins to be laundered every year, unless you had another forty-five thousand customers?’ he asked. He paused once again. ‘Because he’s laundering money,’ said Dennis, clearly pleased with his little pun.

‘Well done, Dennis,’ said the head of department. ‘Prepare a full report and I’ll see that it ends up on the desk of our fraud department.’

Try as he might, Mario could not explain away 3,000 tablecloths and 45,000 napkins to Mr Gerald Henderson, his cynical solicitor. The lawyer only had one piece of advice for his client, ‘Plead guilty, and I’ll see if I can make a deal.’

The Inland Revenue successfully claimed back two million pounds in taxes from Mario’s restaurant, and the judge sent Mario Gambotti to prison for six months. He ended up only having to serve a four-week sentence — three months off for good behaviour and, as it was his first offence, he was put on a tag for two months.

Mr Henderson, an astute lawyer, even managed to get the trial set in the court calendar for the last week in July. He explained to the presiding judge that it was the only time Mr Gambotti’s eminent QC would be available to appear before his lordship. The date of 30 July was agreed by all parties.

After a week spent in Belmarsh high-security prison in south London, Mario was transferred to North Sea Camp open prison in Lincolnshire, where he completed his sentence. Mario’s lawyer had selected the prison on the grounds that he was unlikely to meet up with many of his old customers deep in the fens of Lincolnshire.

Meanwhile, the rest of the Gambotti family flew off to Florence for the month of August, not able fully to explain to the grandmothers why Mario couldn’t be with them on this occasion.

Читать дальше