Anyway, listening to myself talking on tape was weird in the same way that listening to myself play the flute on tape was. That’s nothing like I always thought I sounded. Erskine says everybody’s voice sounds weird to them because you normally hear yourself differently from the way other people hear you, because of some of the sound being carried to your ears through the bones in your skull. Sounds travel differently through solid objects, he said, which I told him would apply more to his head than to mine.

He said he always figured mine was hollow.

What he should do is get contact lenses when he’s older. His eyes are very attractive.

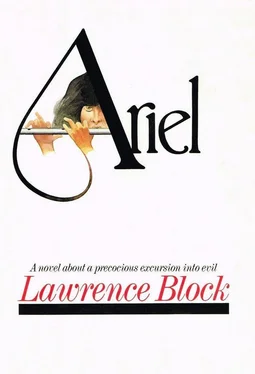

Anyway, tomorrow he can listen to Ariel Plays the Flute. He says once that’s over and done with I’ll be able to play in front of him with no hassle, but I don’t know about that.

What’s funny is I can play with Roberta in the house and it never bothers me. Of course I don’t actually play in front of her. And the fact that I know she’s not listening probably makes it easier.

The following afternoon the two of them walked home from school together. Ariel had not brought the recorder to school so they walked to her house to pick it up. The maroon Buick didn’t show up. She thought she’d seen the car twice since the time she and Channing had taken a long look at each other, but there had been no confrontation since then.

Roberta’s car was gone when they reached the house. “Come on in,” Ariel suggested.

“It’s okay. I’ll wait out here.”

“Nobody’s home. Roberta’s out somewhere. You’ve never seen my house.”

“I can see it fine from here. Just get the recorder and we’ll go to my place.”

“We always go to your place.”

“I’m a creature of habit.”

She started for the door. Then she changed her mind and turned around. “The thing is,” she said, “I really want you to come in.”

“Fuck it,” he said. “I don’t mind.”

“The reason I like you is you’re charming.”

“I was wondering what it was.”

She led him into the house and up the stairs to the second floor. The tape recorder was all packed up in its canvas carrying case. He asked her if she wouldn’t like to play it then and there but she shook her head. “Listen to it by yourself,” she said.

“You’d be embarrassed?”

“I guess so.”

“Did you play it back or anything? Or haven’t you listened to it either?”

“I listened to it twice. Two and a half times, actually, and then Roberta came up and said maybe it was a little late for music. Meaning it was driving her crazy. Two and a half times that I listened to it plus the time I played to record it. She didn’t even know it was a tape and she said I’d be tired today from playing so long. Oh, and look at this. She gave me this the day before yesterday. Teach Yourself to Play the Flute. ”

“Is it any good?”

“How would you like it if your mother gave you a book that would tell you how to turn the car radio on and off?”

“Oh.”

“It’s the worst. If you go all the way through the book you wind up learning how to play Go Tell Aunt Rhody and Be Kind to Your Web-Footed Friends. Just what I want to sit around and do. The thing is she thinks she’s being nice to me. I’m tons more advanced than the book but she doesn’t have any idea.”

“What song did you say? Not Web-Footed Friends but the other one.”

“Go Tell Aunt Rhody.”

“I never heard of it,” he said. “What are you supposed to tell old Aunt Rhody?”

“That her bird died,” Ariel said. She sang:

Go tell Aunt Rhody

Go tell Aunt Rhody

Go tell Aunt Rho-o-o-ody

The old gray goose is dead.

He looked at her. “That’s it?”

“There’s other verses telling what he died of and how broken-up Aunt Rhody is, but that’s it. That’s all the notes there are to play in it.”

“It’s got a nice beat to it,” he said solemnly, “and the words tell a story, and you could dance to it. I’d give it about a seventy-five.”

They went downstairs and she showed him through the first floor. In the kitchen she poured two glasses of milk and found a package of chocolate-covered graham crackers.

“It’s a neat house,” he said.

“I hope we don’t move.”

“Why would you move?”

“Crazy Roberta. She wants to sell the house and move.”

“Where to?”

“I don’t know.”

“Like out of the neighborhood or what?”

“I don’t know. She’s crazy, that’s all. The house spooks her or something. I heard her talking to David and she was saying the same thing on the phone the other day.”

“Do you think you would really move?”

“Who knows?” She rinsed out her glass in the sink, turned to him. “Aren’t you going to finish your milk?”

“I’ve had enough.”

“Then give me your glass. Roberta’s been acting really weird lately.”

“How?”

“Oh, giving me strange looks when she doesn’t think I’m paying any attention. I’ll get a glimpse of her out of the corner of my eye and there’s old Roberta studying me like a rare species of insect.”

“Ugh.”

“Sorry,” she said. Erskine had a thing about bugs, and it even bothered him to hear about them. “I’m glad I was adopted. Otherwise I’d worry about going crazy like Roberta. I wish I didn’t have to wait until I was eighteen.”

“I suppose you could try lying about your age.”

“Funny.”

“You were going to work on David, weren’t you? To find out if he knows anything?”

“I haven’t gotten around to it yet.”

“Well, don’t expect too much, anyway. Even if you find out who your mother is, she’ll probably turn out to be just as bad as Roberta. You met my mother, don’t forget.”

Ariel had met Mrs. Wold several days earlier when the woman was returning home from work just as Ariel was getting ready to leave. Mrs. Wold was a tall overbearing woman, her slate gray hair pulled severely back from a bulbous forehead, and she had spoken with the overprecise enunciation of a kindergarten teacher. “I am so happy to meet you, Ariel. I want to tell you how much Mr. Wold and I appreciate your spending time with Erskine. We are both just so pleased that he finally has a friend. You know, Erskine is a very special child. His health is extremely delicate and that has affected his development in many ways. Believe me, Ariel, my husband and I are both very grateful to you.”

Erskine had been in the room throughout this little speech. Afterward he and Ariel could hardly look at each other.

“Parents are horrible,” he said now. “Real or adopted, it doesn’t make any difference. Parents suck.”

“And what happens when you’re a parent?”

He shook his head. “That’ll never happen.”

“Why? If kids are better than parents, wouldn’t you want to have some around?”

“Are you kidding? Actually bring something into your house that’s going to know what a total shit you are? That would be really stupid, Jardell.”

She stared at him. “Erskine Weird,” she said.

“Very funny.”

“Come on,” she said. “I’ll show you the upstairs.”

“We were already there.”

“Have to get the tape recorder anyway. And all you saw was my room. Come on.”

“What are you doing?”

“Blowing out the pilot light.”

“Why?”

“No particular reason. Come on. ”

She showed him the master bedroom and he was not surprised by the twin beds. “They had a double bed at the other house,” she told him. “But they got rid of it when we moved.”

Читать дальше