“And the woman with the shawl—”

“All kinds of possible explanations. Maybe you’ve got some psychic ability yourself.”

“It never showed up before.”

“Well, maybe you’ve got late-blooming ESP. Maybe you sensed Caleb was in danger, and maybe this intuition manifested itself by your waking from a dream and seeing things in the corners of the bedroom. Or, for the sake of argument, maybe there really was a ghost and she shows up three nights before somebody in the house dies. I remember reading a lot of English novels set in lonely houses on the moors where the family dogs all howl when someone in the family’s about to expire. I know it’s a cliché, but it probably got to be one because it occasionally happened.”

“Then you think Caleb died of natural causes.”

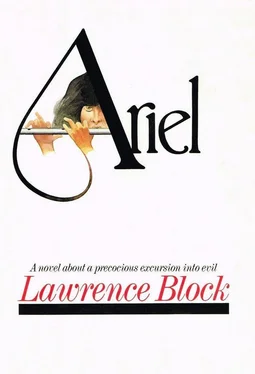

“I think it makes a good working assumption. I think it’s also possible that David killed him, or that Ariel killed him, or that some malignant force in the house itself killed him. I think all sorts of things are theoretically possible. Hell, they’re possible in more than a theoretical way. The point is that it’s impossible to know what’s true and what isn’t, at least for the time being.”

“Where does that leave us?”

“On a county road eight or ten miles west of the Ashley River.”

“You know what I mean.”

“Of course I do. We haven’t cleared up any mysteries, have we? Maybe I just wanted to have this conversation so I’d have a sense of doing something. But there’s not really very much I can do, is there?”

“There’s nothing anybody can do.”

“Not to raise Caleb from the dead, no. You still have your own life to live, Bobbie.”

She nodded. “This is the first day I’ve felt half-alive since he died.”

“It’s the country air.”

“That’s not all it is.”

He had his eyes on the road. The sun was behind them. He was driving east now, and in another ten minutes they’d be crossing the bridge into Charleston. He’d drop her off. She’d be back in her own house, back in her own life.

No, she thought. No, she did not want to let go of him. Not just yet, thanks all the same.

She put her hand on his leg, just above the knee. He turned his eyes from the road, and sexual tension sprang between them like an electrical current jumping a gap.

His response gave her a sense of power, of confidence. She moved her hand deliberately along his thigh, thrilling at his sharp intake of breath. By the time her fingers rested upon his groin, her own heart was pounding and her underarms were damp with perspiration. She rubbed him urgently, rhythmically, and felt a rush of warmth in her own loins.

“Bobbie—”

“Can you find a motel?”

“Do you think it’s a good idea?”

Her fingers worked his zipper. She felt wonderfully in control, and at the same time felt herself surrendering to something more powerful than herself.

“God, Bobbie!”

She lowered her head to his lap, closed her eyes. Her mind was awash with images and fragments of sound, and for an instant all she could think of was Ariel, pale-faced Ariel, playing her magic flute.

They stood at the corner, waiting for the light to change. “It’ll snow pretty soon,” Erskine said. “It’s cold enough already. I bet it snows tonight.”

“I hope so.”

“You do?” He looked at her curiously. “You like snow?”

“It’s pretty.”

“I suppose so. I hate it myself.” The light changed and they crossed the street together. “It’s one block that way,” he said, pointing to the left, “and half a block over.”

She felt uncertain about going over to his house, and had agreed largely because she had run out of excuses. Lately he had met her every day after school and walked her as far as her house, and for the past week he had invited her to visit at his house.

“I have a short-wave radio,” he’d told her. “You can hear lots of things, ham operators and stations from overseas. Most of the time the hams just talk about their rigs, the antennas and transmitters and receivers they’re using and everything. It gets pretty technical. And the regular stations play a lot of music and have newscasts.”

She had said that it didn’t sound terribly interesting. “It isn’t,” he said, “but doing it is interesting.”

It hadn’t sounded all that interesting to her. Finally that afternoon she had invited him into her house.

He had hesitated. “The thing is,” he said, “your mother’s home. There’s her car.”

“So?”

“So I don’t like adults very much. Especially people’s parents. Of course maybe your parents are different.”

“They’re not.”

“Well, at least my mother’s liberated. In other words she works, which means I’m liberated because nobody’s home. There’s stuff to eat and we could listen to the radio until you get bored with it. If you want.”

She hadn’t much wanted to, but at that point there was no decent way out. Now, as they turned the corner into his street, she was glad she had decided to come. She liked his house the minute she saw it, a tall old house like her own but much narrower.

“It’s a nice house,” she said.

“I guess so,” he said carelessly. “We’ve always lived here. It belonged to my mother’s father before I was born, and he went on living with us until he died. I was about four at the time. No, I guess I was five. Not that it matters.”

“Do you remember him?”

“I don’t remember what he looked like, except there are pictures of him, so I know what he looked like. It’s hard to know what you remember. He smelled funny. I don’t remember just what it was about him but he had a funny smell.”

“All old people do. At least my grandmother did.”

“Is she alive?”

“No.”

“We’ll go in the front door. I’m supposed to go in the side door, so I always go in the front. If they don’t like it it’s just T.F.B.”

“T.F.B.?”

“Too fucking bad. Well, you asked, didn’t you?”

“Gross,” Ariel said.

The interior of the house reminded her of her own, but there was a difference and it did not take her long to realize what the difference was. This house had been occupied by the same family for fifty years or more, and it had a settled air about it, the feeling a house develops as a result of continual occupancy by the same people. Her own house had the same sense of age, but the rugs and furniture, the pictures on the walls, all had been placed there too recently to have become part and parcel of the house that contained them.

She liked her house better than Erskine’s. But she preferred the way his house felt.

Of course she didn’t mention any of this. When you said things like that all you got was funny looks.

His room was on the third floor. They went up the stairs to the second floor together, then walked along a hallway to a door that opened onto the attic staircase. Erskine flung open the door and tore up the steep flight of stairs as if something were pursuing him. She stared after him, then followed him at a deliberately leisurely pace. He was still panting furiously by the time she reached the top.

She looked at him, thinking again what a weird kid he was. She was growing to like him more, the more time she spent with him, but he did not seem any more normal than he had at first. If anything she was simply discovering new ways in which he was weird.

The other day, for example, he had dropped the license numbers on her.

“Your mother drove past our house yesterday afternoon,” he said. She had nodded, unimpressed. “I could tell by the license number,” he went on. “664-AQT. The Datsun. Your father has the Ford Torino. LJK-914.”

Читать дальше