Grandpa turns and looks at her, raising his head up from the floor. Turtle comes closer. He jaws, searching for her name, can’t find it, opens and closes his mouth. He says, “Julie— I can’t . . .”

“Goddamn it, Daniel! What is it? What? What?”

Martin grabs Grandpa’s chin, and they look at each other.

“What did you— What were you—?” Martin says.

“Julie—” Grandpa says.

“Kibble, go upstairs,” Martin says.

“I’m sorry,” she says. She’s looking right at Grandpa. “I’m so sorry. I’m sorry.”

Grandpa is looking at her. Whatever he means to say is dark to her. The center is draining out of him, the substance, he is saying the things that it is his habit to say, but he is not saying what he means and he cannot get at what he means.

“Go!” Martin says, and she gets up and runs up the stairs, thinking, this will come to nothing. He will come back from this. She runs into her room, leans against the wall, gasping and listening. From below she hears Martin say, “Tell me what you see, Dad. Tell me what you meant.” She waits in excruciating silence, trying to still her breathing. She is afraid that she will miss what Grandpa says for the sound of her heart, for the sound of her breathing, but she is hungry for air, starved for it. Downstairs, a rasp, the sound of movement, and Turtle stops breathing, listens. “Oh, I see . . . I see . . .” Grandpa says, slurring, and the sound of his feet scraping against the floor, shifting where he lies, and Martin says, “Daniel, look at me— I’m— It’s me, Martin. It’s Martin. Look at me.” And Grandpa says, “Oh, never mind.” Martin, in disbelief, says, “What? What?” There is a long silence, Turtle trying to calm her hitching breath, listening for any sound from downstairs, but there is no sound, and then Martin, his voice a low rasp, hushed with awe or with something else. “You bastard,” he says. “You goddamn bastard.” Then a long interval of silence, Turtle with her back to the door, listening, measuring out her breath to calm it. Then she hears the ambulance, watches it come up the drive. She listens to the strange men downstairs, talking. They are calling out numbers she does not understand, talking to one another, and Turtle walks back and forth in her room, crosses to the window and watches Grandpa carried out on a stretcher and loaded into an ambulance in the muddy yard. Daddy talks to the techs and afterward climbs into his truck and follows the ambulance down the drive. Turtle is left alone, leaning into the window well, roses and poison oak framing her in a tangled border.

Late that night, Martin’s truck comes roaring up the gravel drive and Turtle stirs from her reverie in the window, hands clutched about goose-bumped shoulders. She climbs carefully out of the window well and goes down the stairs and stands out on the porch. Martin walks up to the steps and kicks them hard and then sits down. He takes out a pack of cigarettes, taps one into his hand, lights it. He draws on it. She comes to sit beside him, and he passes her the cigarette and taps a second into his hand. “Dead on arrival,” he says. “DOA.” He clears his throat, and in the doctor’s hushed, affected tone, he says, “‘Daniel has suffered a massive hemorrhagic stroke of the left middle cerebral artery. It started as an ischemic stroke, which means that a blood clot lodged in the artery that profuses the left hemisphere of the brain and the regions responsible for speech and for movement. We do not know where the clot came from. However, the blood vessels in an alcoholic’s brain are very fragile, and he subsequently ruptured and bled out into the brain tissue.’ It was, apparently, painful but fast. Not that he could tell you. The first stroke, the ischemic one, that wasn’t painful. He didn’t know what was happening. But the second stroke, the hemorrhagic one, that was painful, but by then he didn’t have the words to express it. Just locked in his own mind with the mother of all goddamn headaches, however briefly. The doctor said, ‘Like a stroke from god.’” Martin blows smoke out the side of his mouth. “Motherfucker,” he says. They sit side by side. He picks gravel from between the deck boards and flicks it into the driveway overgrown with chicory and goosefoot. She sits in silence and thinks of the ambulance going up the Shoreline Highway, passing bays and headlands in alternation, and her here, waiting. She thinks, I killed him. The thought comes so quickly, so painfully, that it makes her shiver in disgust, grinding her teeth, and she thinks again, I killed him. Her own insignificance is oppressive to her—that she should be the one who finally kills Grandpa, when so much else had failed, and it seems to her that her own relationship to Grandpa is shallow compared to his relationship with Martin, and if Grandpa’s relationship with her had been less troubled, it was only because it had less depth. Grandpa was hard on Martin because Martin engaged his whole character in the way that Turtle engages Daddy’s whole character. And there was something Martin had needed from his own father. Some question left unanswered.

Daddy rises and turns and kicks the porch step riser again. “Fuck!” he yells. He turns and looks down the hillside and yells, “Fuck!” Then he walks heavily back inside and Turtle sits alone on the dark porch until he returns with a five-gallon can of gasoline. He stands for a moment and then he begins to walk past her along the path through the orchard to Grandpa’s trailer in the raspberry field.

“Wait,” she says.

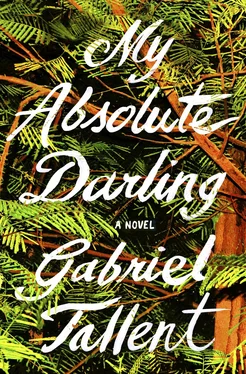

He turns and looks back, and his face softens, his brow furrowing with pain, standing there with the gas can in one hand, his shoulders slumping, his left eye squinting more than the right, and he says, very softly, with tremendous emphasis, “Oh, kibble. Oh, my absolute darling.” He sets the gas can down and he walks toward her. She stands on the porch, utterly bereft. He takes her in his arms.

She says, “I want to die.”

“Oh, kibble,” he says.

She says, “I hate myself. I hate myself.”

“Oh no,” he says, clenching her in his arms. He runs his fingertips between her ribs, following the grooves. They flex and give within his grasp. She feels herself small in his arms. Her face, she feels, fixes itself in some expression of pain and loss, and she says again, “I want to die.”

“Oh, kibble,” he says into her neck. He sucks air through his teeth, a painful sound, expressive of his regret. “He killed himself. I hope you see that. He killed himself and there was nothing either you or I could do. Fuck, I hate him for that.”

“Don’t,” she says softly, her own voice surprising her with the strain.

He shudders, holding her. She is pressing her face into his shoulder, and he holds her this way, cupping his hand around the back of her head.

“I wish to hell it had been different,” he says. “I wish you had had the grandpa you deserved and not the one you had. But it’s just you and me now, kid. Come on.”

He releases her, and takes her hand, and leads her through the orchard to the trailer, and when they get there, Rosy appears in the window, yapping and agitated. Martin opens the door and comes in and Rosy goes galumphing around the linoleum floor. Turtle climbs up the stairs after him and stands in the doorway. Looking around the trailer now, at Grandpa’s things, they all have significance and meaning to her—they seem filled with his presence, and at the same time, they have shrunk, they are awful and painful in their shabbiness. She looks at the dinky foldout table with its cheap cribbage board, the plastic pegs still there from their last game, the deck of cards on the table, and she looks to the paper bag Grandpa used for his recycling, with bundles of frozen-pizza boxes folded there. There is the tiny oven, an ugly mustard color. She looks down the hallway to the bedroom, the mildewed rayon sheets, black mold on the corroding aluminum windowsill with its pebbled plastic window. Christ, she thinks, has it always been this awful? She walks to the cabinets and opens one, and there is a bottle of Jack Daniel’s and two rocks glasses and a plastic water cup and nothing else, the cabinet lining peeling up in places to show the cheap fiberboard beneath. Christ, she thinks. She opens the fridge, and there is a carton of half-and-half and some AA batteries. Christ, she thinks again with gathering painfulness. She leans against the counter. The pain comes on in dull waves, followed by the realization that he is dead, a realization that seems to have layers and depth, a realization she could go down and down into, as if into deeper and deeper water, mounting pressure. The pain is in her stomach and in her lungs, and it fills her with self-disgust and self-hate. Standing in the dingy trailer, she thinks, I want to die. I truly want to die. It is only my cowardice that keeps me from doing it.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу