Turtle rises, squares her stance, levels the front sight with her right eye. She knows the sight is level when the edge appears as thin as a razor—if the gun tips up, she gets a telltale sheen off the sight’s top surface. She revises that edge into a thin, bare line, thinking, careful, careful, girl. In profile, the card makes a target as thick as a thumbnail. She eases the play out of the 4.4-pound trigger, inhales, exhales to the natural slackening of her breath, and rolls on those 4.4 pounds. She fires. The top half of the card flutters down in a maple-seed spiral. Turtle stands unmoving except for quivers that chase themselves down her arms. He shakes his head, smiling a little and trying to hide it, touching his lips dryly with his thumb. Then he draws another card and holds it up for her.

“Don’t be a little bitch, kibble,” he says, and waits. When she doesn’t move, he says, “Goddamn it, kibble.”

She checks the hammer with her thumb. There is a way it feels to hold the gun right and Turtle dredges through that feeling for any wrongness, the edge of her notch sight covering his face, the sight’s glowing green tritium bead of a size with his eye. For a suspended moment, her aim following her attention, his blue eye crests the thin, flat horizon of the front sight. Her guts lurch and drop like a hooked fish going to weeds and she does not move, all the slack out of the trigger, thinking, shit, shit, thinking, do not look at him, do not look at him . If he sees her across those sights, he makes no expression. Deliberately, she matches the sights to the quaking, unfocused card. She exhales to the natural slackening of her breath and fires. The card doesn’t move. She’s missed. She can see the mark on the target board, a handsbreath from him. She decocks the hammer and lowers the gun. Sweat is lacy and bright in her eyelashes.

“Try aiming,” he says.

She stands perfectly still.

“Are you going to try again or what is this?”

Turtle locks back the hammer and brings the gun from hip to dominant eye, the sights level, coequal slots of light between the front sight and the notch, the tip so steady you could balance a coin upright on the front post. The card in contrast moves ever so slightly up and down. A bare tremor answers to his heartbeat. She thinks, do not look at him, do not look at his face. Look at your front sight, look at the top edge of your front sight. In the silence after the gunshot, Turtle relaxes the trigger until it clicks. Martin turns the unharmed card over in his hand and makes a show of inspecting it. He says, “That’s just exactly what I thought,” and tosses the card to the floorboards, walks back to the table, sits down opposite her, picks up a book he’d set open and facedown on the table, and leans over it. On the boarded-up window behind him, the bullet holes make a cluster you could cover with a quarter.

She stands watching him for three heartbeats. She pops the magazine, ejects the round from the chamber, and catches it in her hand, locks the slide back, and sets the gun, magazine, and shell on the table beside her dirty plate. The shell rolls a broad arc with a marbly sound. He wets a finger and turns the page. She stands waiting for him to look up at her, but he does not look up, and she thinks, is this all? She goes upstairs to her room, dark with unvarnished wood paneling, the creepers of poison oak reaching through the sashes and the frame of the western window.

That night Turtle waits on her plywood platform, under the green military sleeping bag and wool blankets, listening to the rats gnawing on the dirty dishes in the kitchen. Sometimes she can hear the clack clack clack of a rat squatting on a stack of plates and scratching its neck. She can hear Martin pace from room to room. On wall pegs, her Lewis Machine & Tool AR-10, her Noveske AR-15, and her Remington 870 twelve-gauge pump-action shotgun. Each answers a different philosophy of use. Her clothes are folded carefully on her shelves, her socks stowed in a steamer trunk at the foot of the bed. Once, she left a blanket unfolded and he burned it in the yard, saying, “Only animals ruin their homes, kibble, only animals ruin their fucking homes.”

• • •

IN THE MORNING, Martin comes out of his room belting on his Levi’s, and Turtle opens the fridge and takes out a carton of eggs and a beer. She throws him the beer. He seats the cap on the counter’s edge, bangs it off, stands drinking. His flannel hangs open around his chest. His abdominal muscles move with his drinking. Turtle knocks the eggs against the countertop, and holding them aloft in her fist, purses open the crack and drops the contents into her mouth, discarding shells into the five-gallon compost bucket.

“You don’t have to walk me,” she says, cuffing at her mouth.

“I know it,” he says.

“You don’t have to,” she says.

“I know I don’t have to,” he says.

He walks her down to the bus, father and daughter following ruts beside the rattlesnake-grass median. On either side, the thorny, unblooming rosettes of bull thistles. Martin holds the beer to his chest, buttoning his flannel with his other hand. They wait together at the gravel pullout lined with devil’s pokers and the dormant bulbs of naked lady lilies. California poppies nest in the gravel. Turtle can smell the rotting seaweed on the beach below them and the fertile stink of the estuary twenty yards away. In Buckhorn Bay, the water is pale green with white scrims around the sea stacks. The ocean shades to pale blue farther out, and the color matches the sky exactly, no horizon line and no clouds.

“Look at that, kibble,” Martin says.

“You don’t have to wait,” she says.

“Looking at something like that, good for your soul. You look and you think, goddamn. To study it is to approach truth. You’re living at the edge of the world and you think that teaches you something about life, to look out at it. And years go by, with you thinking that. You know what I mean?”

“Yes, Daddy.”

“Years go by, with you thinking that it’s a kind of important existential work you’re doing, to hold back the darkness in the act of beholding. Then one day, you realize that you don’t know what the hell you’re looking at. It’s irreducibly strange and it is unlike anything except itself and all that brooding was nothing but vanity, every thought you ever had missed the inexplicableness of the thing, its vastness and its uncaring. You’ve been looking at the ocean for years and you thought it meant something, but it meant nothing .”

“You don’t have to come down here, Daddy.”

“God, I love that dyke,” Martin says. “She likes me, too. You can see it in her eyes. Watch. Real affection.”

The bus gasps as it rounds the foot of Buckhorn Hill. Martin smiles roguishly and raises his beer in salute to the bus driver, enormous in her Carhartt overalls and logger boots. She stares back at him unamused. Turtle climbs onto the bus and turns down the aisle. The bus driver looks at Martin and he stands beaming in the driveway, a beer held over his heart, shaking his head, and he says, “You’re a hell of a woman, Margery. Hell of a woman.” Margery closes the rubber-skirted doors and the bus lurches to a start. Looking through the window, Turtle can see Martin raise his hand in farewell. She drops into an open seat. Elise turns around and puts her chin on the seat back and says, “Your dad is, like—so cool .” Turtle looks out the window.

In second period, Anna paces back and forth in front of the class with her black hair gathered into a wet ponytail. A wetsuit hangs behind her desk, dripping into a plastic bin. They are correcting spelling tests and Turtle hunches over her paper, clicking her pen open and closed with her index finger, practicing a trigger pull with no rightward or leftward pressure at all. The girls have thin, weak voices, and when she can, Turtle turns around in her chair to lip-read them.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

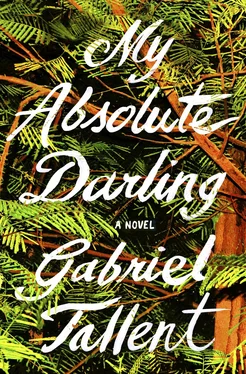

Купить книгу