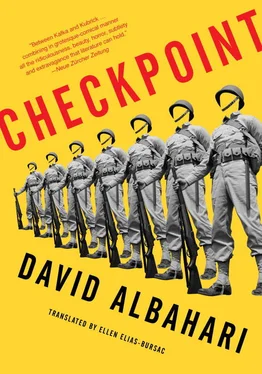

David Albahari

CHECKPOINT

FROM WHERE WE STOOD, the logic of setting up a checkpoint on this particular spot was clear—this was the highest point on a road that rose and fell just as steeply up to and away from the barrier and sentry box. Though we never actually measured it, the stretch of road leading uphill was the same in length as the stretch running down. If somebody were to walk from one side, from below, from exactly where the slope began, while somebody else was walking up from the other side at the same time—assuming, of course, that all the elements of their stride were equal and they were moving at the same pace—the two would reach the barrier at the exact same moment. In fact, each would arrive simultaneously at their side of the barrier, and from there they’d stare beyond the barrier at the other. On their way back, assuming the same conditions, of course, the same would occur. In other words, both would reach the level part of the road that extended in front of them and disappeared off into the forest. We never spent time in the forest, not because we’d been told not to but because we were all from the city so the forest meant nothing to us. Had one of us gone into the forest, he probably never would have reappeared, the only exception being Mladen, who’d lived on a mountainside. The forest for him was home sweet home, and it may be that our whole platoon was assigned the task of guarding the barrier and checkpoint because of Mladen’s knowledge of forest flora. Apparently, he’d given the right answer to the question about what soldiers should eat if they’re forced to hunker down in the wild. So that’s how we ended up here, at least for now, and after the first week it’s looking as if we won’t be reassigned any time soon. This was a conclusion we came to on our own because during that first week no one showed up at either side of the barrier, and the radio that was supposed to connect us to the command center fell silent the second day after we arrived and would later kick in now and then only at the odd moment. The soldiers didn’t dare carry cell phones because of their interference with the military network, and none of the three phones the unit had were working as there was no electric power available for recharging. So, having no contact with headquarters or the world, we could be said to be as lost as castaways surrounded by a boundless expanse of ocean. Worst of all, we had no way of knowing which route we’d taken to get there. The trucks that brought us drove through the night and unloaded us before dawn on the broad path leading through the forest all the way to the checkpoint, and then immediately, while everything around us was still dark, they turned around and back they went. When dawn finally broke, no one was sure which road the trucks had used. All around us were tire tracks, of course, but they crisscrossed and overlapped every which way so we couldn’t identify the road leading back to home base. But we only began to wonder about this a few days later once the unusual quiet of the place had begun to stir our qualms, by which time the tire tracks were barely visible, especially on the grass that had straightened since then. We had no choice but to continue doing what we’d come there to do: guard and watch over the passing of people and goods through the checkpoint. To be honest, we hadn’t even been told whether the checkpoint was on a border lying between two countries or along a line dividing two villages. Perhaps it didn’t matter. A soldier’s duty, after all, is not to reason why, his is but to obey and only then ask questions—meaning, if we’d been told to guard the checkpoint, that’s what we’d do, and we wouldn’t distract ourselves with idle guesswork. So our commander promptly drew up a roster of sentries, cutting back on the number of daytime sentries so the soldiers would be more rested at night, when, for security reasons, there were four on duty. Nothing moved around us by day or night—all the sentries concurred, but our commander, an old-school soldier, had no intention of relenting or reducing the number of sentries on night duty. “Where nothing squeaks,” our commander said, “that’s where the trouble is brewing.” So we guarded a checkpoint where nobody was checked and peered through our binoculars at landscapes through which no one passed. If there was a war still on somewhere, we knew nothing about it. No shots were fired, there was no zinging of bullets, no bomb blasts, no helicopter clatter, nothing. “What if the war’s already over,” we asked our commander one morning, “shouldn’t we be going home?” He was implacable. “We’ll go home when they send us home. Until then, here we stay.” The soldiers protested, stood there, cried, “Release us, send us home!” The commander did what he could to quiet them but without success. A fractious mob is a fractious mob, whether they’re soldiers or civilians. No one listened to the commander, so, in the end, he had to resort to an unappealing but tried-and-true remedy: the pistol. Raising it high above his head, he barked that he’d start shooting if they didn’t all shut up and return to their posts. A shot was heard. The commander stared, aghast, at his pistol; but the shot hadn’t come from him. It had come from the gun of one of the sentries who, after we’d assembled by the checkpoint, reported to the commander in a quavering voice that he’d shot when he thought a man in green fatigues had shot at him first. “This is not a thinking matter,” barked the commander. “Did he or did he not shoot at you?” “He took aim,” said the guard, “but I was faster.” The commander sent a group of soldiers to examine the place where the person in the green fatigues had supposedly stood, and they ran off across the meadow. Someone said maybe a bear had devoured a woodsman earlier, and everyone burst out laughing. A little later the group of scouts waded back through the brambles. They were holding something green, which turned out to be a tatter of ragged fatigues. Nowhere, however, said the scouts, did they find anything to suggest that this filthy, rumpled tatter was what the sentry had seen. Nowhere, they insisted, was there any trace of humans, nothing but paw prints and bird tracks. Did this mean the sentry hadn’t seen anything? The commander said nothing. Then he announced the alarm was over and called an assembly. We lined up and, while the sun warmed our heads from behind, we listened to the commander’s warning to remain calm if we wished to grapple with the enemy. True, we knew nothing of who the enemy might be, but once a war is on one speedily acquires both friends and foes. Back we went to our duties—at least those of us who had duties—and our leisure activities, and soon the strains of an accordion could be heard. The cook’s helpers brought news of the goulash we’d be served for dinner and there were rumors that there might be cake, which sparked elation among the soldiers and helped them forget how horrific our situation was. But then the horror showed its ugly face with the commander’s order that over the next few days, or rather, nights, we were to use lights only in cases of the most dire need, and all evening activities such as polishing boots, cleaning weapons, and longer stays outdoors would be reduced to a minimum or switched to daytime. Then smoking came up, which had not been permitted in enclosed areas but only at a distance of ten feet from the building where the men were billeted. We should explain that the checkpoint was not new, nor were the barracks where we were housed, with sleeping quarters, a lecture hall, a bathroom, a mess hall, and a small room for the commander.

Читать дальше