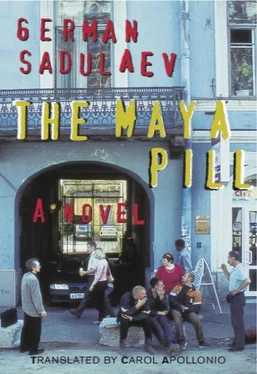

The Maya Pill took its translator on an exciting ride from Russia’s present-day urban reality to its hazy mythical roots and back again. Fresh words abound. Sadulaev’s language presents unique challenges that begin with the novel’s very title, Tabletka . By choosing this title—the word means “pill”—the author foregrounds the little pink hallucinogenic pills of his central plot, which were by some oversight included in a shipment from Holland to the Russian frozen food company’s warehouse. A literal translation (“The Pill”) would send the English-language reader down a garden path of irrelevancies; in spite of the novel’s abundance of themes, birth control is not one of them. “The Tablet,” too, would suggest wildly unrelated matters, from trivial items like notepads and computers to such profundities as Moses’s Ten Commandments. The Dutch pills lead Maximus to confront the nature of reality and perception—the classic Russian theme of beauty, which may or may not save the world—in the form of the Goddess of Sex, Spring, and Fertility who appears to him in the office elevator. She is the Hindu goddess of illusion, that force that veils true reality, and her name is Maya. Hence the English title. The titles of the novel’s four parts are also worthy of note: Itil, Samandar, and Serkel are names of lost cities of Khazaria, and Part IV, “Mack” ( mak ), is both the Russian word for poppy and the protagonist’s tabooed nickname.

Sadulaev’s rich and varied language reflects the novel’s themes. When referring to pop culture, the Internet, the streets and eateries of St. Petersburg, and the modern workplace, the style is jazzy, modern, and witty. A completely different diction takes the reader into Saat’s life in ancient Khazaria. Saat is illiterate, his perceptions visceral, his moral compass true. He is the classic wise fool who serves and suffers in an unjust economy and an unjust war. Saat bears witness to “misfortune, woe,” in short sentences that are the more powerful for their clumsiness. Saat’s naïve and awestruck perception of life in the Khazar capital bears the novel’s political allegory. Blue flashing lights attached at their horses’ tails clear the roadways for the oppressors as they sweep through town, just like the lights on Kremlin officials’ vehicles speeding through Moscow. The military requisitions officer confiscates Saat’s horses, including a tender foal that is of no use for the war effort, but will make a perfect pet for his children. Through it all, Saat observes and tries to understand. Sadulaev’s satire is light and humorous, but carries a bite. As always, wordplay and humor present a challenge to the translator. The best example is the description of the elections in ancient Khazaria, to which the voters proceed in a zombielike state, with their brains divided into segments supporting different political parties. Sadulaev found these “party-portions” out in a field somewhere, in a dialect word for manmade beehive boxes— bortii —which, yes, do sound sort of like “parties”— partii in Russian, a word as alien to Saat as bortii is to the compilers of the Oxford Russian-English dictionary, not to mention to a host of otherwise convenient Internet tools. The solution to this problem comes from author himself, who dubs them, in English, “peehives.” Various words conveying emptiness— pustota , pustosh , pustynia —which serve the novel’s theme of perception and reality, present another challenge. What seems to a Russia in economic thrall to nimbler neighbors west and east to be an empty, barren landscape— pustosh —fills, in dreams, with economic, cultural, and philosophical potential.

Even when English is a good servant to Sadulaev’s Russian, some elements transit over uneasily. Not everyone, notably the female half of our readership, will savor the sex scenes with equal relish. All three male protagonists illustrate distinctive cultural attitudes toward sex, and in all cases, the reality of the experience is mediated through a particular form of storytelling: literary, oral, and virtual. Readers of all tastes are urged, however, to appreciate the easternmost lovers’ use of (genuine) ancient Chinese poetry as foreplay. Sadulaev situates his China scenes within the perspective of the country’s millennia-long history, which colors his characters’ attitudes toward business as well as to sex and family life. The big picture above all; and above all, patience. It may also help to keep in mind that Maximus’s lover Maya functions more as muse than mistress, and the Dostoyevskian story she tells of sordid child abuse is not meant to be taken literally. Maximus, after all, is a writer, and the book in your hands is a story about its own creation—and the devil’s role in that creative process. More treacherous still for contemporary Western readers is the Dutch partner’s foray into the Internet sex chat room staffed by a Russian girl, with all its attendant nuances. More often than not, the sex scenes are better interpreted as reflecting cultural differences and attitudes toward illusion and reality than as serving some prurient purpose or social message. As for Sadulaev’s political themes, they participate in a gritty Russian literary tradition that wallows in the mud as it strives to solve the great problems of ontology, and for all that, exerts an unmistakable fascination upon its often bewildered readers—as it always has.

As they conduct their international business transactions, Sadulaev’s characters resort to the universal language of trade—English. Maximus’s dreams occasionally leave traces of the ancient Khazar language in his consciousness as well; the reader—like the translator—is unlikely to be able to decipher them, though readers proficient in Arabic may fare better. Russian novels have always been hospitable to heterogeneous intrusions, and The Maya Pill is no exception. Here can be found various interpolated histories: of the post-Soviet economy, of Khazaria, of the mythical origins of Rus. A dip into the chaos of the Internet yields a series of posts by a barely literate blogger that, for all their misspellings and crude vocabulary, do manage to lead Maximus to the secret of the fish paste, and from there, to the true nature of the pink pills.

The Maya Pill , like its hallowed literary predecessors, offers a panoramic picture of the contemporary social and economic world even as it probes deep into our assumptions about the nature of reality. True to the novel’s ambitions, the eternal “accursed” questions of Russian literature lurk quietly on every page. Here, though, they come with an understated irony that should endear itself to a modern readership that has heard and read it all before, or thinks it has.

Carol Apollonio Durham, NC, 2013

GERMAN SADULAEV was born in 1973, in the town of Shali, in the Chechen-Ingush ASSR, to a Chechen father and Terek Cossack mother. In 1989, aged sixteen, he left Chechnya to study law at Leningrad State University. Today he lives and works as a lawyer in St. Petersburg.

CAROL APOLLONIO is Professor of the Practice of Russian at Duke University. She is the author of Dostoevsky’s Secrets: Reading Against the Grain , and is a translator of Russian and Japanese literature.

SELECTED DALKEY ARCHIVE TITLES

MICHAL AJVAZ, The Golden Age .

The Other City .

PIERRE ALBERT-BIROT, Grabinoulor .

YUZ ALESHKOVSKY, Kangaroo .

FELIPE ALFAU, Chromos .

Locos .

IVAN ÂNGELO, The Celebration .

The Tower of Glass .

ANTÓNIO LOBO ANTUNES , Knowledge of Hell .

Читать дальше