There’s a telephone on the wall near the counter in the café for customers to use. You can call anywhere in the city for free and talk as long as you want, so long as there isn’t some antsy girl waiting in line behind you looking at her watch. And so long as it’s a direct number. This number was the most direct imaginable. All seven numbers were the same. I procrastinated a moment wondering if there were even any numbers in our area code with that prefix. But it could have been a new system with its own fiber-optic cables, or something, operating independently from the regional phone system.

I dialed the number. A girl’s voice answered. I gave my name, and she said simply: “I’ll connect you.”

Then a man’s voice came on the line. I gave my name again. He said:

“Delighted. Come right over to the office, and we’ll go through the contract.”

Which caught me off guard.

“But I haven’t told you what I want yet…”

His answer didn’t quite match: “We knew you would call.”

He transferred me back to the girl, who told me how to get to the office. It wasn’t that far from Nevsky Prospect; in fact, it was quite close to the café where I was making the call. Soon I was at the address, standing by the door. There wasn’t anything special about it, no gothic monograms or anything like that. Just a doorbell. I pushed it.

I heard footsteps on the other side, and a girl opened the door and invited me inside.

“Come with me. I’ll take you…”

Judging from the sound of her voice, it was the same girl who’d answered the phone.

We passed through a large foyer and went down a long corridor to a spacious office, where a man was sitting behind a massive desk. Apparently the girl and this man, her boss, were the only people working here. Such extravagance, thought I, and right in the center of the city, with its insanely high rents for commercial space! They must own the building.

The man stood up when I entered the room.

He didn’t look at all like Al Pacino. Young, blond, with soft features. There was absolutely nothing infernal about his appearance. He shook my hand; his grip wasn’t too firm, wasn’t too limp: just right. He didn’t hold my hand for too long, didn’t pull back his hand too early, and his palm was dry and warm. Everything was ideal—creepily so.

“Hello! Glad to see you! Have a seat.”

He indicated a comfortable chair in front of a small coffee table at the wall, and instead of going back to his desk, he took a seat in a chair on the other side of the table, just like mine, exactly the same height. Perfect manners.

“To tell you the truth, we’re a little pressed for time. I have to close the deal today and submit a report.”

“I’m ready. I’ve just been a little busy, finishing up my book.”

“Good for you! Was it difficult?”

There was nothing forced or artificial about his tone. Just sincere interest and concern. The question could just as well have been about my decision or my literary labors… I preferred to believe the latter.

“How to begin… actually, this is harder. When you finish a book, you think that you’ve already said and done everything you could, and you don’t know why you should bother to go on living… Time to die, pal, you tell yourself. But the days go by, weeks, months, and you accumulate new experiences, new ideas come to you. Or maybe they’re just new words and images for the same old thoughts. And the conclusion you reach is always the same, essentially: Just keep on doing what you’re doing. Keep on pushing that boulder up the hill, dance while the music is playing, fight on without worrying about victory or defeat. Everyone finds his own image, the only possible thought for him or her, and tries to communicate it to the world. We have no choice! But a feeling of emptiness at a certain stage is unavoidable.”

“I understand. I hope that the fruit of your labor was worth all the effort.”

“Sometimes it seems to me that any normal person who’d read my book would have only two questions: First, what was the author smoking? And second: Is there any more?”

He laughed the beautiful laugh of a healthy, genial, self-assured man.

“Well, that’s hardly the worst reaction! Your literary experiments are undoubtedly extremely interesting. But let’s get down to business. Please take a look at the terms of the contract.”

There was a stack of papers lying on the table. He slid it over to my side.

I skimmed the dozen or so pages, which were covered with fine print, and said, “All right. I agree.”

“Then let’s sign.”

I have to admit that I was still a little nervous. I’d made a point of bringing a pen from home. I got it out and pricked my finger with the sharp end.

A single drop of scarlet blood spilled onto the white page next to my signature.

He gave a satisfied smile and, gathering up the signed contract, noted: “That was not at all necessary.”

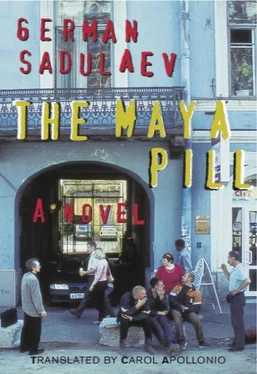

The feisty concoction you’ve just (perhaps) finished reading is the product of the restless, fertile mind of Russian-Chechen author German Sadulaev. Sadulaev has proven to be one of the most original and prolific writers of the post-Soviet generation; his works have drawn a broad readership and critical acclaim. The Maya Pill , his first novel (and second book) to appear in English, was short-listed for both the Russian Booker and National Bestseller prizes, and his subsequent Chechnya-themed novel The Raid at Shali was also short-listed for the Russian Booker. I am a Chechen , a genre-bending collection of legends, stories, and reminiscences situated amid the wars in Chechnya, appeared in English in 2010, and has been translated into several other languages as well.

The “loose, baggy monsters” of the classic Russian literary tradition offered a broad, realistic picture of the social, cultural, and political life of their times even as they probed inward into the human psyche and outward into the universe. True to those roots, Sadulaev’s novel abounds in themes both trivial and profound. His protagonist commutes to work, swipes in with his smart card, scrolls lazily through his inbox, and performs his duties as a cog in the wheel of the new Russian capitalism. On this level, The Maya Pill offers as complete a picture of twenty-first century Russian office culture as can be found in modern fiction. But that is just the surface—and Russian thinkers have always mistrusted appearances. Maximus, it turns out, is a dreamer, a writer, an armchair philosopher. In his dreams he is Saat, humble Khazar horse-herder and future great Khagan, spokesman for the common people, ruler of the boundless steppe. Saat’s Khazaria, with its wars of aggression, its political intrigues, its neglect of the earth and its injustices to the little man, is Post-Soviet Russia, thinly veiled. Saat is also the child Maximus, who on his trips home to his grandmother, gathers armloads of poppies. And the frozen French fries that his company sells—do they even exist? Or are they, like the material world itself, a product of the imagination, of Maya—pure, distilled illusion? Or perhaps the culprits are Dutch hallucinogenic pills—derived from those very poppies, mixed into a heady fish paste and introduced into Western Europe long ago by itinerant Khazar merchants? Behind it all, the devil is at work, offering fame and fortune in exchange for human souls. Maximus treads a complex path indeed. His duties as a mid-level import-export manager lead him into contact with business partners in Holland and in China. Their paths, it turns out, run parallel to his. All three of them face the challenge of finding love in an alienating, virtual world. Are the women they meet just Maya, illusion, like the imaginary French fries that the Dutch are selling to the Russians? Sadulaev is nothing if not ambitious, and the attentive reader will reap rich rewards as all these plotlines come together at the end, when the devil comes in to close the deal, and when you learn that the novel you have just read has told the story of its own creation.

Читать дальше