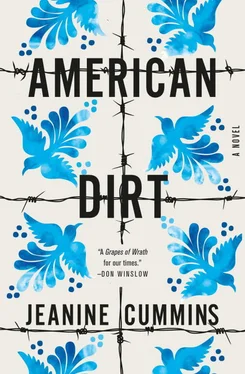

Жанин Камминс - American Dirt

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Жанин Камминс - American Dirt» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2020, ISBN: 2020, Издательство: Tinder Press, Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:American Dirt

- Автор:

- Издательство:Tinder Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2020

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-4722-6138-0

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

American Dirt: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «American Dirt»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

FEAR KEEPS THEM RUNNING.

HOPE KEEPS THEM ALIVE.

Vivid, visceral, utterly compelling, AMERICAN DIRT is the first novel to explore the experience of attempting to illegally cross the US-Mexico border. cite empty-line

9

empty-line

11 empty-line

14

American Dirt — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «American Dirt», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Which brings me to the final, most significant factor that influenced my decision to tackle this subject. It took me four years to research and write this novel, so I began long before talk about migrant caravans and building a wall entered the national zeitgeist. But even then I was frustrated by the tenor of the public discourse surrounding immigration in this country. The conversation always seemed to turn around policy issues, to the absolute exclusion of moral or humanitarian concerns. I was appalled at the way Latino migrants, even five years ago – and it has gotten exponentially worse since then – were characterized within that public discourse. At worst, we perceive them as an invading mob of resource-draining criminals, and, at best, a sort of helpless, impoverished, faceless brown mass, clamoring for help at our doorstep. We seldom think of them as our fellow human beings. People with the agency to make their own decisions, people who can contribute to their own bright futures, and to ours, as so many generations of oft-reviled immigrants have done before them.

When my grandmother came to the States from Puerto Rico in the 1940s, she was a beautiful, glamorous woman from a wealthy family in the capital city, and the young bride of a dashing naval officer. She expected to be received as such. Instead, she found that people here had a very reductionist view of what it meant to be Puerto Rican, of what it meant to be Latinx. Everything about her confused her new neighbors: her skin tone, her hair, her accent, her notions. She wasn’t what they expected a boricua to be.

My grandmother spent much of her adult life in the States but didn’t always feel welcome here. She resented the perpetual gringo misconceptions about her. She never got past that resentment, and the echoes of her indignation still have some peculiar manifestations in my family today. One of the symptoms is me. Always raging against a perceived slight, always fighting against ignorance in mainstream ideas about ethnicity and culture. I’m acutely aware that the people coming to our southern border are not one faceless brown mass but singular individuals, with stories and backgrounds and reasons for coming that are unique. I feel this awareness in my spine, in my DNA.

So I hoped to present one of those unique personal stories – a work of fiction – as a way to honor the hundreds of thousands of stories we may never get to hear. And in so doing, I hope to create a pause where the reader may begin to individuate. When we see migrants on the news, we may remember: these people are people.

So those were my reasons. And yet, when I decided to write this book, I worried that my privilege would make me blind to certain truths, that I’d get things wrong, as I may well have. I worried that, as a nonmigrant and non-Mexican, I had no business writing a book set almost entirely in Mexico, set entirely among migrants. I wished someone slightly browner than me would write it. But then, I thought, If you’re a person who has the capacity to be a bridge, why not be a bridge? So I began.

In the early days of my research, before I’d fully convinced myself that I should undertake the telling of this story, I was interviewing a very generous scholar, a remarkable woman who was chair of the Chicana and Chicano Studies Department at San Diego State University. Her name is Norma Iglesias Prieto, and I mentioned my doubts to her. I told her I felt compelled, but unqualified, to write this book. She said, ‘Jeanine. We need as many voices as we can get, telling this story.’ Her encouragement sustained me for the next four years.

I was careful and deliberate in my research. I traveled extensively on both sides of the border and learned as much as I could about Mexico and migrants, about people living throughout the borderlands. The statistics in this book are all true, and though I changed some names, most of the places are real, too. But the characters, while representative of the folks I met during my travels, are fictional. There is no cartel called Los Jardineros, nor is that fictional organization based on a specific cartel, though it does reflect the general nature and composition of the cartels I encountered in my research. La Lechuza is not a real person.

One thing I had to learn while doing research for this book was to strangle the word American out of my own vocabulary. Elsewhere in the Western Hemisphere there’s some exasperation that the United States has co-opted that word, when in fact the American continents contain multitudes of cultures and peoples who consider themselves American, without the hijacked cultural connotations. In my conversations with Mexican people, I seldom heard the word American used to describe a citizen of this country – instead they use a word we don’t even have in English: estadounidense, United States–ian. As I traveled and researched, even the notion of the American dream began to feel proprietary. There’s a wonderful piece of graffiti on the border wall in Tijuana that became, for me, the engine of this whole endeavor. I photographed it and made it my computer wallpaper. Anytime I faltered or felt discouraged, I clicked back to my desktop and looked at it: También de este lado hay sueños.

On this side, too, there are dreams.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I’m grateful to so many people for helping this story become a book.

For reading early drafts of this novel and being honest about how bad it was: Carolyn Turgeon, Mary Beth Keane, Mary McMyne. For reading later drafts of this novel and encouraging me in the right directions: Pedro Ríos, Bryant Tenorio, Reynaldo Frías, Alma Ruiz. For reading almost-finished drafts of this novel and sharing invaluable expertise: Bob Belmont, Jenifer A. Santiago, Alejandro Duarte.

For allowing me to observe their important work, and patiently teaching me things about Mexico and immigration I never would’ve understood without their insight: Pedro Ríos (again, a thousand times) from American Friends Service Committee, Laura Hunter from Water Stations, Elizabeth Camarena from Casa Cornelia, Robert Vivar from Unified US Deported Veterans, Norma Iglesias Prieto from San Diego State University and the Colegio de la Frontera Norte, Sister Adelia Contini from Instituto Madre Asunta Esmeralda Siu Márquez from Coalición Pro Defensa del Migrante, Joanne Macri from the NYS Office of Indigent Legal Services, Enrique Morones from Border Angels, Cesar Uribe from Rancho el Milagro, Padre Óscar Torres from the Desayunador Salesiano Padre Chava, Misael Moreles Quezada from Rancho San Juan Bosco, Father Pat Murphy, Andrew Blakely, Kate Kissling Blakely, and all the staff at the Casa del Migrante in Tijuana, Padre Dermot Rodgers and friends, from Saint Peter of Rome Roman Catholic Mission. Thank you to Gilberto Martínez for showing me around Tijuana and sharing cultural insight with me. Thank you to Alex Renteria from the US Border Patrol for answering my questions. Thank you to all the brave men and women I met in different stages of their journeys who talked to me about their experiences.

I’m grateful to the following writers, whose work you should read if you want to learn more about Mexico and the realities of compulsory migration: Luis Alberto Urrea, Óscar Martínez, Sonia Nazario, Jennifer Clement, Aída Silva Hernández, Rafael Alarcón, Valeria Luiselli, and Reyna Grande.

I’m super grateful to my agent, Doug Stewart, for his friendship, enthusiasm, and perfect pitch. I’m indebted to Amy Einhorn for loving this novel, and for not settling when it was good enough. Thank you to Mary-Anne Harrington for being absolutely devoted to this book. Thanks to my foreign rights team, Szilvia Molnar and Danielle Bukowski. Thank you to Caspian Dennis at Abner Stein. Thank you to everyone at Flatiron for their passion and brilliance, especially Nancy Trypuc, Marlena Bittner, Conor Mintzer, Bob Miller, Cristina Gilbert, Katherine Turro, Keith Hayes, Emily Walters, Vincent Stanley, and Don Weisberg. Thank you to Cecilia Molinari for elevating this book with a precise, sensitive, and perfectly bilingual copyedit. Thank you for all the global support from the team at Tinder Press and Hachette Australia. Also, to all the publishing people who aren’t working on this book, but believed in it, and support it even though it’s not their job: Megan Lynch, Sonya Cheuse, Libby Burton, Carole Baron, Emily Griffin, Asya Muchnick. To Rich Green at The Gotham Group, and to Bradley Thomas at Imperative Entertainment, thank you.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «American Dirt»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «American Dirt» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «American Dirt» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.