No one is looking at us and I don’t much care if they are, so I take her hand and lift it to my lips and kiss it. Jude has beautiful hands, long and slim, the joints not at all obvious, the nails almond-shaped and always unpainted. Kissing hands is an erotic thing for us – she kisses mine too – and sometimes it’s just a loving thing with a meaning of I’m here and all will be well. But will it? If all being well means a baby, I think it’s more likely to be all being ill.

We take a taxi at Huddersfield station, a rather magnificent Victorian building, and it gets us to Godby in twenty minutes. Rather to my relief – though from the messages and fervent apologies he left behind him not to his – the owner of Godby Hall, a computer tycoon named Brett, has been called away to Bradford for an urgent meeting. His wife, as the au pair who comes to the door tells us, is visiting her sick mother in Scarborough and has taken the baby with her. That, at any rate, pleases me. One of my missions in life is to hide babies from Jude, though I don’t really know whether the sight of one upsets her or if it’s just that I think it must.

Godby Hall is in serious need of painting outside, its white walls and columns streaked with blackish greenish trails where water has spilt down it from the gutters. In Henry Thomas’s day, I suppose it was blackened with soot from factory chimneys. Indoors it’s anaemic-looking, everything painted white, pale rugs lying about on pale woodblock floors, and it looks cold, though it doesn’t feel it with the central heating going full blast. The au pair, who’s German and speaks perfect but heavily accented English, takes us up to the second floor where the day and night nurseries were. I marvel, not for the first time, at the way the Victorians and pre-Victorians placed their children as far away from their own quarters as possible.

I start wishing Jude hadn’t come, it was she who insisted on coming, though there’s nothing in this room to show it was once a night nursery. It’s the au pair’s own room now, one end lopped off to make an en-suite bathroom, but, apart from being rather untidy, it’s as bleak as the rest of the house. The unmade bed has a pink and white duvet bunched up and flung across one end of it. There’s a built-in clothes cupboard and a built-in dressing table the au pair calls a vanitory, its top laden with cosmetics of all kinds, jars and bottles and tubes. I try to imagine where the two beds were and what else might have been in this room. Toys? Books? The equivalent of the ‘vanitory’, a washstand perhaps, would have held a great many medicaments for poor Billy. Were candles in use upstairs at Godby Hall or did they use colza lamps in which coleseed oil was burned? Downstairs, probably, but up here it would have been candles. And now I remember that Amelia refers in one of her letters to lighting the candle when she goes to attend to Billy in the night.

Jude is looking out of one of the sash windows and I join her. We admire the view of green hills and dark woodland and in the foreground the village of Godby, cleaned of smoke deposits and spotless in the icy March sunshine. The wind is so strong that even from this distance we can see the weathervane on the church tower furiously spinning round. The houses that were built for the mill workers look from here as if each one of them has been radically converted into a dwelling for the young upwardly mobile, smartened with Sandtex and brightly re-roofed, a green strip of lawn with shrubs running between their backs. I imagine Henry kneeling up here on a window seat or ottoman, looking at the familiar view and then, perhaps, creeping back to relish the sight of blood splashes on his brother’s pillow.

‘The younger one, Billy, he died, didn’t he?’ It’s Jude asking and she looks sadly at the corner where I’ve suggested his bed might have been. ‘How old was he when he died?’

‘He was six.’

The au pair looks suitably aghast and asks why he wasn’t given antibiotics. To do her justice, she probably knows nothing of any of this and supposes Billy died twenty or thirty years ago.

‘This was a hundred and fifty years ago, more than a hundred and fifty,’ I tell her. ‘There wasn’t a cure for tuberculosis. He coughed and his lungs bled, he got thinner and weaker and in the winter of eighteen forty-four he died.’

‘There were two boys, I think?’ The au pair has picked up a bottle of something off the ‘vanitory’ and is spraying the inside of her wrist with whatever is inside it. ‘What happened to the other one?’

‘He grew up and became the Queen’s doctor – not this queen, her great-great-grandmother – and had six children and was made a lord.’

‘Why didn’t he et tuberculosis?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘If everyone in the nineteenth century who was exposed to it caught it,’ says Jude, ‘there wouldn’t have been any people left in England.’

This is an exaggeration but I know what she means. The au pair asks if any of Henry’s children died.

‘One of them did. His second son.’ I’m nervous of talking about all these children in front of Jude, those that lived and those that died young, but she seems quite tranquil and the sadness has gone out of her eyes. ‘His name was George and he died in nineteen hundred and eight, just a year before his father. But his father was seventy-two and he was eleven.’

The au pair is persistent. ‘Was that tuberculosis too?’

‘Perhaps, but I don’t think so,’ I say. ‘It sounds more likely to have been leukaemia, but it’s only guesswork on my part.’ I suddenly feel nauseated by it all, the room and the knowledge that the boys slept here, and Billy suffered here and died here, and I suggest we go outside and have a look round the garden.

It’s too cold to stay outdoors for long. Besides, everything has changed utterly in a century and a half, which is only what I’d expect. There’s a big oak that was probably a young tree when Henry was small, he may even have climbed it, but otherwise all the trees and shrubs are replacements, and second and third replacements, for the ones that were there in his day. We come indoors again and into Amelia’s drawing room, which she must have crowded with knickknacks and antimacassars and wax fruit under glass domes and gros point cushions, but has recently been furnished by someone who prefers the stark look. The au pair says Mrs Brett has told her to give us a drink and offer us lunch but we’re both so eager to turn this down that we come out with a, ‘Oh, no, thank you very much,’ in unison and call for a taxi on Jude’s mobile.

We get lunch in Huddersfield very late, at nearly half-past two, and decide not to do as we’d planned and stay the night at a hotel in York but to go home on the next available train. We’re going to France for Easter so it’ll be nice to have a few days at home first. Jude takes my hand and says she supposes I’ve noticed she’s got her period. Like her, I count the days and become, for her sake, only for her sake, more and more strung up and alternately hopeful and despairing as the crucial day approaches. Maybe it’s fortunate for both of us that she’s absolutely regular, almost to the hour. Yet even if it hadn’t come, how many weeks this time would she have carried a child?

‘You thought it upset me,’ she says, ‘all that talk about the children and children dying, but it didn’t, not really. It was all so long ago.’

‘A lost world where they order things differently?’

‘Something like that,’ she says as we get into the train.

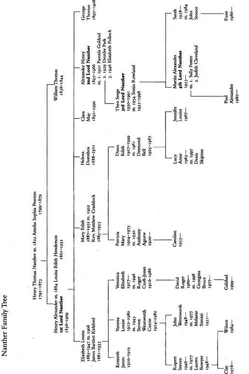

Henry’s elder son Alexander, the one who didn’t die, was my grandfather. I remember him well and visiting him in Venice. And now, back in my study at the scarred dining table, I think about the two dead boys: Billy, who succumbed to tuberculosis in 1844, and George, who died of some incurable illness in 1908. How did Henry feel when his younger son died? He was an old man, the boy more like a grandson surely than a son. Clara implies that George was fond of his father, at any rate that he didn’t dislike him as the rest of them did, but this may only be a case of the Youngest Child Syndrome, according to which even unaffectionate parents lavish love on the last to come into the family. Henry wrote many learned works on diseases and deficiencies of the blood but, perhaps naturally, never refers among the cases he mentions to his son’s condition. He kept a diary of a sort, that is he kept a bald record of what he had done, read, written and where he had been each day, but there is very little in the entries about his feelings, nothing at all in the later ones. His peculiar writings on blood, the notebook essays, are an almost metaphysical jotting down of his innermost responses to aspects of blood and disease and pain. They remind me in a way of Sir Thomas Browne and Religio Medici.

Читать дальше