‘The time at which the House adjourns tonight and tomorrow night,’ he says, ‘is entirely in your Lordships’ hands.’

Earl Ferrers, who looks everyone’s idea of a general commanding an army, gets up and asks why the chief whip is always asking for restraint. Some noble lords are going to be restrained for the rest of their lives so why should they be restrained on the Bill that is perforce to restrain them?

And so it has begun. Lady Jay, the Lord Privy Seal, opens it with the words, ‘My Lords, I beg to move that this Bill be now read a second time,’ and one after another, from all benches, they put their cases. Peers come and go, leaving quickly and entering slowly, always pausing to give a court bow to the Cloth of Estate. I go out for tea when the debate adjourns, and when I come back again it is a quarter past five and Baroness Young is saying from the Conservative benches that this is one of the saddest days of her political life. The Bill, she says, means the end of the House of Lords and the end of hundreds of years of history. It won’t lead to a chamber with democratic legitimacy, for life peers are just as undemocratic as hereditary peers.

She goes on for a long time in this gloomy way and when she’s finished I’d like to get up and say that if there’s no democracy in this House, and there can’t be in her view since it’s composed exclusively of lifers and hereditaries, the best solution would be to abolish it altogether and we’ll all go home. But I can’t speak since I haven’t put my name down on the list. When I look round again I see that Jude has come into the Chamber and taken her place below the bar. She’s had her hair done and is wearing a very elegant black trouser suit. It’s only a couple of years since women started wearing trousers in here and an even shorter time since the wives of peers did. Trousers are not a good idea on overweight women but, come to that, they’re not a good idea on overweight men, only they don’t have a choice about it. I smile at Jude and she raises her eyebrows and smiles at me and I mouth, ‘Dinner?’ and she mouths, ‘Yes.’

Lord Trefgarne is speaking now, pointing out, very much to the dismay of those who haven’t counted, that nearly two hundred lords have their names down to speak in the two days’ debate. He says that he has no intention of confining his speech to seven minutes and goes on to ask if the Government realize what a tough battle they have to face. It is six o’clock. I get up and leave, pausing to let Jude precede me out of the Chamber and into the Peers’ Lobby. We head for the Peers’ Guest Room and a drink.

‘It’s not as if you won’t all keep your titles,’ says Jude, over her large glass of Chardonnay. ‘You’ll still be called “my Lord” or “your Grace” or whatever and your heirs will still inherit.’ I’m touched by Jude’s attempt to reassure, especially as this comes from the woman who is known as Lady Nanther and ‘my Lady’ only in here, and otherwise spurns her title and insists on being known as Judith Cleveland. ‘I can’t see what all the fuss is about. Half of them never come in here.’

I ask her what she thinks Henry would have said about it. She takes a keen interest in Henry and likes discussing him, even though Paxton Osborne, where she’s a senior editor, won’t be publishing the Life .

‘They’ve tried to reform the House of Lords before, haven’t they?’ she asks. ‘I mean, in the nineteenth century and again in 1911? He wouldn’t have been surprised at the idea.’

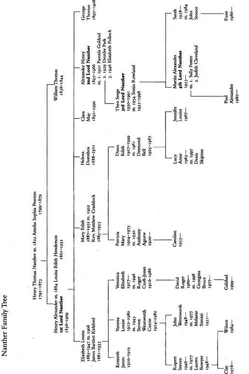

‘He died in nineteen-oh-nine,’ I say. ‘He came in here very little but he valued the peerage. Isn’t that why he was so desperate for an heir? All those girls born, one after another, four of them before the son finally came.’

The shadow I’ve sworn I’ll never provoke again passes across her face and I want to bite my tongue or cover up my mouth. But I’ve done it again and now it’s too late. She doesn’t say anything about it, she seldom does these days, she doesn’t need to because the pain is there in the tiny wince and the attempt at a smile. It’s only about five seconds before she’s talking again, telling me of a letter about Henry she’s come across in the biography of a musician they’ve just had come in. She’s even brought me a photocopy of it and as I take it from her I feel a thrill of excitement go through me. It’s just possible I’m going to begin discovering some of the thoughts that went through Henry’s head.

2

The letter from the musician’s mother has joined the others in Correspondence One on the table. ‘One’ because it was written when Henry was still fairly young and practising at St Bartholomew’s Hospital. The mother had taken her son, who was to grow up a world-renowned violinist, to Henry expecting a diagnosis of haemophilia on the grounds of his frequent nosebleeds. Here she is writing jubilantly to her cousin of the result of the consultation:

Dr Nanther is a most charming, courteous and very handsome man. He had little to say to Caleb, no doubt understanding that a child of seven, however talented, is without judgement or self-knowledge, but was very gracious to me. In the course of our conversation I told him, as I was bound to do, though with great fear in my heart, of my husband’s uncle who had the Bluterkrankheit or what we would call Haemophilia and died from a haemorrhage at the age of fifteen. Imagine my joy, dearest Christina, when Dr Nanther, explaining with great patience, told me that a boy could inherit that disease only through his mother, never through his father, that, in his judgement, what Caleb suffered was a mere Epistaxis or a chronic bent towards nosebleeds and that he would grow out of it…

Grow out of it, we know from this biography, he did and lived to be nearly eighty. More emerges from this letter about Henry than about the child. He apparently had a highly developed bedside manner. His photographs had already told me he was good looking but not, of course, that he was courteous and gracious. To the mother, very likely a young and pretty woman, he behaved charmingly, while he took no notice of the child.

Henry Nanther was born at Godby near Huddersfield on 19 February 1836, elder son of Henry Thomas Nanther, a woollen manufacturer and active Wesleyan. His mother was Amelia Sophia, daughter of William Pearson.

That is Dictionary of National Biography stuff. Plain unadorned facts. Though his entry states that Henry was the eldest son it naturally makes no comment on the fact that his parents had been married for fourteen years before he was born. These days you come across plenty of couples married for many years before having children but that is the result of careful planning, the woman wishing to succeed in her career, the establishment of a suitable home for a family, and so on. No family planning existed in Henry Thomas and Amelia Sophia’s day. So what happened? Did she have miscarriages – and this is something I know plenty about – or give birth to stillborn babies? Did conception for some reason never happen? Women who worry about their failure to conceive are less likely to conceive than those who are carefree. So Jude was told by her doctor, as if it was conception she had trouble with. It seems unlikely that Amelia didn’t worry, given the times she lived in and the fact that the woman was inevitably blamed in cases of failure to produce children.

At last a child came along. By that time Amelia would have been over her anxiety, for she was past her mid thirties and may have given up the idea of becoming a mother. The baby, to be baptized Henry Alexander, was born at the family home, Godby Hall, a handsome healthy child. Within two years of his birth another son came along, but this one was different. With very little evidence to go on, it’s hard to know precisely what was wrong with William Thomas Nanther, but, given that his mother was in her late thirties at the time of his birth, it sounds as if he was a Down’s Syndrome child. This would be a likely explanation for his being described in Amelia’s letters to her sister Mary as ‘strange’, ‘backward’ and ‘different-looking’. In one letter she writes, ‘Billy looks not at all like either Mr Nanther or me. The village people call him a changeling, which hurts my feelings when I hear it, though I try not to attend to the opinions of ignorant folk.’

Читать дальше