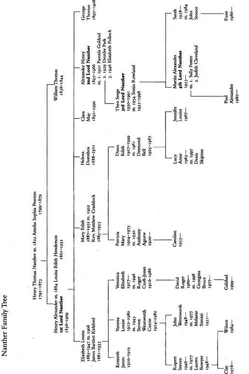

Henry Thomas Nanther was the owner of a woollen mill and most of the able-bodied population of Godby worked in it. Rows of back-to-back cottages had been built climbing the hillsides to accommodate the families who had moved there for the sake of certain employment. The Nanthers lived in a big house, built in the Georgian style, a little outside the village; a white stucco building, not particularly suitable for the Yorkshire climate, to the front of which Henry Thomas had added a monstrous portico with a domed roof, supported by eight disproportionately fat columns with Corinthian capitals. It’s still there, or the exterior is, and the interior hasn’t been much altered.

To their credit, Henry Thomas and Amelia kept Billy at home rather than committing him to some kind of institution. No doubt they were aware of just how dreadful such a place would have been, comparable, I imagine, in awfulness to the children’s homes and homes for the mentally ill which still exist in Eastern Europe. Or worse. Henry Thomas was wealthy and, if he and his wife were never quite accepted by the local gentry, they were respected. He was a deeply religious man, assiduous in carrying out his duties as a Methodist lay preacher, and determined to practise what he preached. Perhaps he genuinely believed it would have been wrong to lay the burden of his second son on other shoulders. Of course there was a children’s nurse at Godby Hall and a nursery maid as well as the usual staff of servants. Billy, according to his mother, was good, sweet and affectionate. Down’s children often are. If it was Down’s. It’s equally possible his incapacity was due to a difficult birth during which his brain was damaged by being temporarily deprived of oxygen. We don’t know and now never shall.

In his elder brother’s second year at the day school he attended at Longfield, three miles away, Billy fell ill. As we know from the fate of several of the Bronte sisters whose home, in Haworth, wasn’t far away, tuberculosis was rife in the hills and valleys of Yorkshire in the 1830s and 40s. That it was contagious was not known at the time or, rather, it was assumed that infections came from ‘miasma’, a kind of noxious vapour that rose from standing water and sewage. Why Billy caught tuberculosis and not his brother or his parents is a mystery. Why, after all, did Emily, Anne and Maria succumb to it while Charlotte and their father remained free of infection?

By this time – Billy was five – his mother had become more attached to him than to his elder brother. And this in spite of what she had earlier written to her sister about his strangeness and retardation. His illness drove her to the edge of insanity. The letters she wrote to Mary are rambling or wild and full of threats to end her own life, ‘if the Lord takes my Billy’. Her husband, perhaps because of his business and commitments at the mill, seems to have been less involved. What was Henry’s attitude? We don’t know. He was at school in a village to which he was taken by pony and trap each morning and fetched home each afternoon. Amelia writes that she had been in the habit of driving him herself, at least for the morning trip, but that this ceased with Billy’s illness. Did Henry mind? He must have done. Those drives constituted perhaps the only times he was alone with his mother. Now he had been deprived of this pleasure by the illness of a brother he had always, according to a worried letter from Amelia to Mary, treated with some amount of contempt.

A progressive doctor who attended Billy told his parents that a dry climate at a high altitude would improve his health and recommended Switzerland or the Bavarian Alps. In 1843, in Yorkshire, that was like telling parents today that they ought to take their sick child to the Antarctic or the top of the Himalayas. But no, even that’s not a parallel. Today’s parents wouldn’t find going to Nepal or the far south nearly as preposterous as Henry Thomas and Amelia found the idea of the Continent. Neither had ever been out of England and neither had any intention of going. Instead, Amelia took Billy to the Lake District. If anything, he grew worse and they returned within a fortnight for Amelia to write to Mary that he had spat blood on three mornings in succession.

Appallingly risky as it seems to us today, the two little boys shared a bedroom. It was called the night nursery and Amelia often mentions it in her letters.

I went into the night nursery at first light this morning [she writes], and found both boys asleep, but for the third time this week there was blood on Billy’s pillow, quite an excessive amount. I felt so sick at the sight after I had hoped and prayed there would be none this time, that I thought I should faint. If only Billy would call me or nurse when he coughs and the dreadful blood comes! But he is so good and – oh, imagine it! – would not want to trouble us.

How much of this coughing did Henry hear and how much blood-spitting did he see? Most of it, surely. Remember that he disliked and despised his brother and felt it was he who occupied the prime place in their mother’s affections. Did he know what coughing up blood meant? Probably. There’s no reason to suppose Amelia was discreet about demonstrations of grief. No doubt Henry witnessed this nausea and these near-faintings. He was seven, the age of reason. His brother coughed up blood and his mother reacted as if the world was coming to an end; therefore the blood indicated Billy was very seriously ill and might die. Isn’t it likely that he too looked for blood on his brother’s pillow and when he saw it rejoiced in what it meant?

I’m wondering – and perhaps I shall always just wonder – if this equating of the evidence on Billy’s pillow with the removal of a rival and with a happier future was the beginning of Henry’s passion for blood.

Jude and I went home after dinner. The House sat till ten past three this morning, finally adjourning after Lord Vivian had given statistics about the number of peers who attend the House daily, and Lord Falconer had asserted that changes under the Act would make the place more independent. They’re going on with the debate today. Easter is coming, the House will rise tomorrow until 12 April, and soon after we shall be at committee stage. Jude has taken two days off and we are going up to Yorkshire to take a look at Henry’s birthplace by invitation of the owner.

Jude is nearly eight years younger than I am, which puts her still very much on the right side of forty. Those few years are precious to her because they mean she still has a chance of a baby. Unlike Amelia Nanther, Jude has no trouble conceiving. It’s carrying a child beyond two or three months that seems impossible for her. I’ve a son from my first marriage, Paul my heir, who in his turn has sat on the steps of the throne. If a child comes I’ll be happy for Jude’s sake. I’d like to see her joy and I do sometimes imagine the things she’d say and the plans she’d make and her face lit up with happiness. But I don’t long for a child in the way she does, and in my heart I don’t believe there’ll ever be one. Jude conceived three years ago but miscarried at eight weeks, conceived again and lost the baby at three months. She’s recently been trying a new treatment but it isn’t working or hasn’t worked yet, I can tell by her face. She’s sitting opposite me in the train, on the side where they have single seats with a table in between, and although she appears perfectly healthy and not pale or unwell, she has that set look about the mouth and misery in her eyes that indicate her period has come.

There’s a kind of parallel there with the way women behaved in the 1840s, menstruation being the forbidden subject. Presumably, Amelia had some form of words in which to tell Henry Thomas she’d be ‘unwell’ for the coming five or six days, but her diffidence came from prudishness and female delicacy. Jude doesn’t tell me because she can’t bear to mention it, she can’t use the word, any of those words that mean another month’s gone by and by the time one more has passed she’ll be thirty-seven. I think she believes I secretly mind but hide my disappointment for her sake. No amount of assuring her of my indifference helps. When we were first together and then when we were first married I’d see the box of Tampax lying about in the bathroom or the cardboard tube floating in the lavatory pan, but now she hides the evidence as if she really is living in some past time. The only sign of her period is in her unhappy eyes.

Читать дальше