If Konstantyn had taken Zaya in before, surely he wouldn’t object to her presence now, for another day or two? Another expended bowl of pork stew, lusciously greasy? She could use him like he’d once used her. So long as she considered it a simple transaction, not a favor, she could let herself knock on his door.

—

“Maybe this is the point,” the clients whisper outside Zaya’s window on the second morning. “Maybe we’re supposed to feel abandoned.”

They take the initiative, find their own ordeals.

“That grassy knoll?” says the stocky venture capitalist, pointing. “To the invalids who lived here, it must have seemed a mountain.” He braids wild grass into ropes, with which he ties thick branches to the sides of his legs, rendering his knees unbendable.

“A few of the orphans might have never even seen it.” The socialite rips a strip off the bottom of her frock, blindfolds herself.

The steel magnate plugs his ears with poplar fluff.

Almaza fills her boots with gravel.

—

On the third morning, when setting out the latrine newspaper (one broadsheet per day), Zaya comes upon a second article about Konstantyn and the tomb, published a week ago.

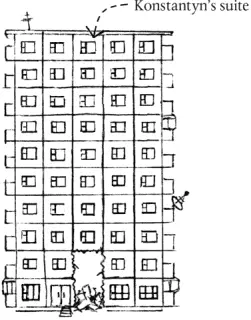

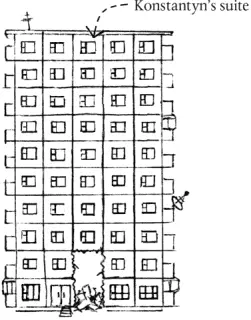

The saint’s tomb had caved in, the article reports. Sheets of vinyl flooring, rugs, furniture, appliances, hot-water radiators, framed photographs, toys, a porcelain dish set, jars of fermented tomatoes—all this piled into the tomb from the apartment above, along with a family of three, shocked but unharmed, their mouths, allegedly, still full of breakfast. Luckily, that morning the tomb was closed, its live-in guard having been fired for undisclosed reasons.

“Must be the shifting earth, the encroaching marshes,” commented Konstantyn Illych Boyko, who had failed to insure his business and, the newspaper noted, had also failed in marriage.

“Must be those inner walls Konstantyn Illych knocked out,” stated the former guard, who had been intercepted at the train station on his way to Kiev, where he would seek employment in customer service. The man, endowed with impeccably white teeth, wished to remain anonymous.

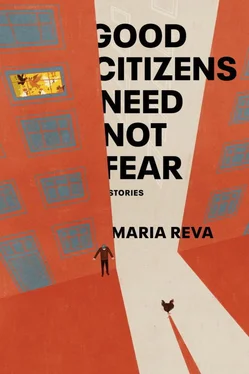

Zaya examines the accompanying photo. She wonders if the apartment block is wide enough for the rest of the structure to remain sound.

“You might want to clear out,” Almaza tells Zaya from the doorway of the latrine. She has tied an off-center knot at the hem of her frock, for a fitted faux-slit look. “I slipped laxatives into the clients’ breakfast. Dysentery day.”

—

On the fourth evening at the internat, visitors start emerging from the forest, crowding the iron gates. Three at first, then five more follow. Most are around Zaya’s age. Among the visitors is a teenage boy, orange-maned, laden with a tattered gym bag. His right eye is pressed deeper into his head than the left. He tells Zaya that he and the others had grown up at the internat, and heard it was reopening. They’d been living on the streets, and now they want back in. When Zaya tries to turn them away, the boy says, “But we walked all the way here.” They’d started at sunrise, and now it was almost sundown. They’d been stalked by a wild boar, dive-bombed by crows. A bunch of them had turned back already. “But we made it,” the boy insists.

Before this job, Zaya herself had been living on the streets, in Moscow’s labyrinthine suburbs, huddling up to the warm aboveground pipes that fed wastewater from power plants to household radiators. “I’m sorry,” Zaya says, but she isn’t. She wants these visitors to go away. It’s as if the internat is rebuilding itself, and soon the real sanitarki will return, a director will materialize.

A round-faced woman among the crowd at the gates smooths her dirty wrinkled blouse over her stomach, as if the blouse is the problem. She points toward Almaza and the clients, who are limping around the courtyard with their legs in splints, pebbles spilling from their shoes. “But you let them in.”

“They paid to be here.”

The group awaits an explanation.

After a pause, Zaya says, “I don’t understand it either.”

“Hey,” says the woman in the wrinkled blouse, “I remember you.”

On second look, Zaya remembers the woman, too, but she feigns ignorance. As a girl, this woman used to follow the sanitarki around, asking for the tips of their braids to make into hair dolls. Now the woman has a pair of thin braids of her own, wispy ends dusting her shoulders. Zaya, on the other hand, has kept her hair buzzed; any time it grows out, the strands feel like fingers on her nape, threatening to stretch around her neck.

“How’d you get to be a sanitarka ?” asks a man with pink heart-shaped glasses too small for his face. Despite the bushy beard, Zaya recognizes him as well.

“I’m not a real one,” Zaya says, more forcefully than she’d intended.

—

The clients are not yet asking for their money back, exactly, but would any of them recommend the place? Of all the other trips the company offers? Sure, the child-size beds are lumpy, the food lousy, the latrines reek, but no one has been properly traumatized. No one is falling apart or pulling themselves back together. And despite efforts to keep busy, the past four days have been downright dull.

It’s also awkward for the clients to be forced to look at all those sad people loitering at the gates. More and more keep showing up. They sleep under sagging tarps. How many now, fifteen? Can’t Zaya get rid of them? It doesn’t help that Almaza barters with them through the gates. She trades slices of the liver paste for their coffee, fresh off their camping stove. She sighs at them in regret. “Honey,” she tells the teenager with the pressed-in eye, “if only we could trade places.”

—

On the fifth day, when Zaya sets out moldy bread and rancid margarine for breakfast, the clients don’t show up. Zaya scopes out the building and the sunny meadow behind it, calling Almaza’s name.

“Over here!” Almaza’s hoarse voice reaches Zaya from the grassy knoll—seemingly, from deep inside it.

Zaya rounds the knoll to discover Almaza and all four clients crouching in a narrow, weed-strewn hole, looking small and scared. The hole is just deep enough to trap them. “What took you so long? We were calling for you all night,” Almaza says, hugging her knees to her chest, her long black ponytail draped around her neck like a scarf. The venture capitalist and steel magnate have their arms wrapped around each other. The lifestyle manager picks at a crown of wilted dandelions atop the socialite’s head.

“Is this one of the graves you told me about?” asks Almaza. “The to-be-filled ones?”

“They were never this deep,” says Zaya.

“This one wasn’t deep, at first, either.” Almaza had stumbled into a shallow pit, everyone else had followed, and the ground beneath them caved in. “There are tunnels down here. We’ve been crawling around, trying to find a way out.” Her face strains; she’s on the verge of tears. “We could’ve been eaten by an animal. Or by a hundred spiders, whose venom would slowly predigest us. Something could’ve happened to you, and we’d be stuck here for days and days until our drivers found our hollowed corpses.” As she lists all the ghastly scenarios, the clients nod along, gasping as one might do when presented with an exotic restaurant menu. Almaza delights in her performance, gesticulates wildly in the cramped space. She takes a dramatic pause. “We’d be like the orphans who died here, buried en masse.”

Читать дальше