All the apartment buildings along the street had their windows open to welcome the sunlight and fresh air.

The sun was warm in May, and the leaves on the trees gave off the fresh fragrance of spring. The trees along the street waved their branches in the light breeze and provided shade on the path. Another small path led to a park surrounded by tall pine trees and flowers that blossomed late into the spring season.

They stopped at a newly painted blue bench.

“Do you want to rest a bit?” asked Jeong Jin Wu.

“Uh huh.”

Jeong Jin Wu helped Ho Nam up onto the bench. They both took a deep breath of the sweet scent of flowers, grass, and pine.

Between some trees and a grassy path, a newlywed couple was walking with an entourage escorting them. They took a picture amid the beautiful scenery with the apartment buildings in the background.

The newlyweds walked toward Jeong Jin Wu and Ho Nam. The groom’s face was as bright as the flower on his lapel. The bride had a corsage pinned to her dress and a crown made of roses. She lifted her long dress so that she wouldn’t trip over it as she walked. Each time she took a step, the tips of her shoes poked out. The bride and groom stood affectionately next to each other. The bride then rested her head on the groom’s shoulder.

The photographer knelt and focused his lens.

Ho Nam seemed entertained by the sight. He stood up from the bench and said, “Isn’t that nice?”

“Uh huh.”

Jeong Jin Wu was immersed in such deep thoughts that he answered without knowing what had been asked.

The photograph of the young couple captured life’s most beautiful artwork, the union and excitement of a new family on this joyous day. For older couples who had endured marriage through the seasons, the wedding ceremony was a fond memory, but for young couples, it was their reality. For the next generation, it would become tradition, society’s gift. The course of human history may seem uneventful, but the joy of one’s wedding day never grows old. This was the everlasting tradition of humanity that no one or nothing could destroy.

“Hey, mister.”

Ho Nam looked serious and continued, “It would be nice for mom and dad to have a wedding.”

Jeong Jin Wu thought Ho Nam would be disappointed if he told the child that his parents had already had their wedding ceremony, like this young couple, long before he had been born. He tried to change the subject.

“Would you like to have some crackers and delicious food?”

“No.”

“Then, what?”

“If there is a wedding, then mom and dad will be better.”

Jeong Jin Wu’s eyes began to sting with tears.

You’re right, child. If your parents had another wedding, then they would be more affectionate with each other, and you would be able to rest secure in their love and be the happy child that you deserve to be. However, what can I say? The wedding that you’re looking at with envious eyes happens only once. One day you will understand the meaning of marriage.

Jeong Jin Wu looked at Ho Nam and tried to temper the child’s hopes. Don’t worry, child. Your parents will remarry. They may not have a wedding ceremony again, but they will renew their wedding vows. It will be a spiritual wedding.

People began to fill the park to enjoy the mild Sunday afternoon.

There are people who dream of building a family, and there are people who already live in one. There is no one without a family. A family is where the love of humanity dwells, and it is a beautiful world where hope flourishes.

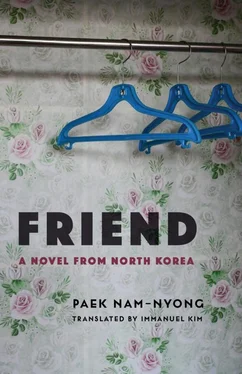

by Immanuel Kim

Paek Nam-nyong’s Friend is one of the few North Korean novels that has reached an international audience. First published in Pyongyang in 1988, the novel was picked up by the South Korean press Sallimteo in 1992, and the French publisher Actes Sud produced a translation by Patrick Maurus in 2011. One reason for this interest is surely the subject matter. In a review in Le Monde , Philippe Pons writes, “[ Friend ] is revealing of a literary approach that began in the 1980s, aimed at getting rid of ‘socialist realism’ and ‘revolutionary romanticism’—idealizing the heroic struggle and sacrifice—to deal with the lives of ordinary people.” Almost all the North Korean writing we have access to in English translation is by dissidents or defectors. Friend is unique in the Anglophone publishing landscape in that it is a state-sanctioned novel, written in Korea for North Koreans, by an author in good standing with the regime.

But Friend is not only of interest for what it can tell an Anglophone reader about North Korea. It is a novel constructed on powerful dialogues, internal monologues, and strong personalities. Paek’s Judge Jeong Jin Wu is concerned with the strength of the North Korean state, but he is equally concerned with universally thorny questions, such as how to balance work and family life and how to allow adults, especially women, the self-determination offered by divorce without causing the affected children undue suffering. Household chores and the social expectation that women will shoulder them even as they pursue careers outside the home are a recurring theme. And as the work’s title hints, Friend also explores the possibilities and limits of a helping hand, whether in the form of official government intervention or social or familial well-wishers, when an individual is struggling or a marriage is on the rocks. That Paek’s vivid psychological portraits also give readers a glance into a famously closed society is an unintended bonus.

History and Style of North Korean Fiction

Friend , of course, did not appear in a vacuum. As a rule, literary works in North Korea show the process of individuals acquiring “correct” political consciousness. Literature translates Party directives into entertaining narratives and models how one should adapt to new sociopolitical situations. The Party, Writers’ Union, and literary critics prescribe guidelines and ensure that artists adhere to them in both the form and the content of their work. Writers like Paek are able to operate within this framework of prescriptions and produce literature that fulfills the Party’s directives while challenging the reader.

Historically, the Party has seen literature as a significant part of national campaigns to materialize Party directives. The Cheollima campaign, for example, in the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s focused on the collective effort of the people to reconstruct the country in the aftermath of the Korean War. A typical book from this period has an optimistic plotline, as the utopian socialist state was projected to be within reach. No problem was too big and no task was too tiresome for the gung-ho heroes and heroines whose nearly supernatural power and devotion to the nation were intended to increase morale among readers. This is the type of literature, with its glorification of work and workers, that will come to mind for many readers when they think of Socialist Realist or even Communist literature more broadly.

Narratives that praise Kim Il Sung became standard in North Korean literature only after the Fifteenth Plenary Meeting of the Fourth Central Party Committee in 1967. Until then, most works of fiction did not depict Kim Il Sung or even mention him. By this point, Kim Il Sung’s supporters had decisively suppressed all other factions within the Party. The 1967 meeting codified the cult of personality that had grown up around Kim as well as officially adopted Kim’s Juche, or Self-Reliance, ideology. Kim’s words and image became commonplace in art and indeed in all public discourse, and writing the phrase “According to the Great Leader Kim Il Sung,” thanking Kim Il Sung, expressing a desire to please him, or using numerous fawning monikers to describe his being became the normative writing practice in North Korea after 1967.

Читать дальше