Kurt Vonnegut - Mother Night

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Kurt Vonnegut - Mother Night» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Mother Night

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Mother Night: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Mother Night»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Mother Night — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Mother Night», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

40: Freedom Again ...

I was arrested along with everyone else in the house. I was released within an hour, thanks, I suppose, to the intercession of my Blue Fairy Godmother. The place where I was held so briefly was an unmarked office in the Empire State Building.

An agent took me down on an elevator and out onto the sidewalk, restoring me to the mainstream of life. I took perhaps Shy steps down the sidewalk, and then I stopped.

I froze.

It was not guilt that froze me. I had taught myself never to feel guilt

It was not a ghastly sense of loss that froze me. I had taught myself to covet nothing.

It was not a loathing of death that froze me. I had taught myself to think of death as a friend.

It was not heartbroken rage against injustice that froze me. I had taught myself that a human being might as well took for diamond tiaras in the gutter as for rewards and punishments that were fair.

It was not the thought that I was so unloved that froze me. I had taught myself to do without love.

It was not the thought that God was cruel that froze me. I had taught myself never to expect anything from Him.

What froze me was the fact that I had absolutely no reason to move in any direction. What had made me move through so many dead and pointless years was curiosity.

Now even that had flickered out. How long I stood frozen there, I cannot say. If I was ever going to move again, someone else was going to have to furnish the reason for moving.

Somebody did.

A policeman watched me for a while, and then he came over to me, and he said, 'You all right?'

'Yes,' I said.

'You've been standing here a long time,' he said.

'I know,' I said.

'You waiting for somebody?' he said.

'No,' I said.

'Better move on, don't you think?' he said.

'Yes, sir,' I said.

And I moved on.

41: Chemicals ...

From the Empire State Building I walked downtown. I walked all the way to my old home in Greenwich Village, to Resi's and my and Kraft's old home.

I smoked cigarettes all the way, began to think of myself as a lightning bug.

I encountered many fellow lightning bugs. Sometimes I gave the cheery red signal first, sometimes they. And I left the seashell roar and the aurora borealis of the city's heart farther and farther behind me.

The hour was late, I began to catch signals of fellow lightning bugs trapped in upper stories.

Somewhere a siren, a tax-supported mourner, wailed.

When I got at last to my building, my home, all windows were dark save one on the second floor, one window in the apartment of young Dr. Abraham Epstein.

He, too, was a lightning bug.

He glowed; I glowed back.

Somewhere a motorcycle started up, sounded like a string of firecrackers.

A black cat crossed between me and the door of the building. 'Ralph?' it said.

The entrance hall of the building was dark, too. The ceiling light did not respond to the switch. I struck a match, saw that the mailboxes had all been broken into.

In the wavering light of the match and the formless surroundings, the bent and gaping doors of the mailboxes might have been the doors of cells in a jail in a burning city somewhere.

My match attracted a patrolman. He was young and lonesome.

'What are you doing here?' he said.

'I live here,' I said. 'This is my home.'

'Any identification?' he said.

So I gave him some identification, told him the attic was mine.

'You're the reason for all this trouble,' he said. He wasn't scolding me. He was simply interested.

'If you say so,' I said.

'I'm surprised you came back,' he said.

'I'll go away again,' I said.

'I can't order you to go away,' he said. 'I'm just surprised you came back.'

'It's all right for me to go upstairs?' I said.

'It's your home,' he said. 'Nobody can keep you out of it'

'Thank you,' I said.

'Don't thank me,' he said. 'It's a free country, and everybody gets protected exactly alike.' He said this pleasantly. He was giving me a lesson in civics.

'That's certainly the way to run a country,' I said.

'I don't know if you're kidding me or not,' he said, 'but that's right'

'I'm not kidding you,' I said. 'I swear I'm not' This simple oath of allegiance satisfied him.

'My father was killed on Tuesday,' he said.

'I'm sorry,' I said.

'I guess there were good people killed on both sides,' he said.

'I think that's true,' I said.

'You think there'll be another one?' he said.

'Another what?' I said.

'Another war,' he said.

'Yes,' I said.

'Me too,' he said. 'Isn't that hell?'

'You chose the right word,' I said.

'What can any one person do?' he said.

'Each person does a little something,' I said, 'and there you are.'

He sighed heavily. 'It all adds up,' he said. 'People don't realize.' He shook his head. 'What should people do?'

'Obey the laws,' I said.

'They don't even want to do that, half of them,' he said. 'The things I see — the things people say to me. Sometimes I get very discouraged.'

'Everybody does that from time to time,' I said.

'I guess it's partly chemistry,' he said.

'What is?' I said.

'Getting down in the dumps,' he said. 'Isn't that what they're finding out, that a lot of that's chemicals?'

'I don't know,' I said.

'That's what I read,' he said. 'That's one of the things they're finding out'

'Very interesting,' I said.

'They can give a man certain chemicals, and he goes crazy,' he said. 'That's one of the things they're working with. Maybe it's all chemicals.'

'Very possible,' I said.

'Maybe it's different chemicals that different countries eat that makes people act in different ways at different times,' he said.

'I'd never thought of that before,' I said.

'Why else would people change so much?' he said. 'My brother was over in Japan, and he said the Japanese were the nicest people he ever met, and it was the Japanese who'd killed our father! Think about that for a minute.'

'All right,' I said.

'It has to be chemicals, doesn't it?' he said.

'I see what you mean,' I said.

'Sure,' he said. 'You think about it some more.'

'All right,' I said.

'I think about chemicals all the time,' he said. 'Sometimes I think I should go back to school and find out all the things they've found out so far about chemicals.'

'I think you should,' I said.

'Maybe, when they find out more about chemicals,' he said, 'there won't have to be policemen or wars or crazy houses or divorces or drunks or juvenile delinquents or women gone bad or anything any more.'

'That would sure be nice,' I said.

'It's possible,' he said.

'I believe you,' I said.

'The way they're going, everything's possible now, if they just work at it — get the money and get the smartest people and get to work. Have a crash program,' he said.

'I'm for it,' I said.

'Look how some women go half off their nut once a month,' he said. 'Certain chemicals get loose, and the women can't help but act that way. Sometimes a certain chemical will get loose after a woman's had a baby, and she'll kill the baby. That happened four doors down from here just last week.'

'How awful,' I said. 'I hadn't heard — '

'Most unnatural thing a woman can do is kill her own baby, but she did it,' he said. 'Certain chemicals in the blood made her do it, even though she knew better, didn't want to do it at all.'

'Um,' I said.

'You wonder what's wrong with the world — ' he said, 'well, there's an important clue right there.'

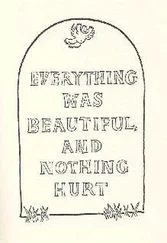

42: No Dove, No Covenant ...

I went upstairs to my ratty attic, went up the oak and plaster snail of the stairwell.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Mother Night»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Mother Night» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Mother Night» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.