Miklós Vámos

The Book of Fathers

Translation copyright © 2006 Peter Sherwood

Originally published in Hungarian as Apák könyve

THE WORLD COMES TO LIFE. WISPS OF GREEN STEAL ACROSS the fields, rich with the promise of spring. Tiny shoots push through the soil. Virgin buds uncoil at the tips of branches. Soft, fresh grass sweeps and swells across the meadows. Thornbushes blossom on the hillsides. The walnut trees have survived the winter, though their antlered crowns still stand bare. Fresh leaves reach longingly for rain from the sky.

The Lord be praised, we reached the village of Kos in the month of April in His Year of 1705. Five times in that year and in the year thereafter was the village laid waste, thrice by the Kurucz bands of the insurrectio Rákócziensis, twice by the Labancz troops of the Emperor. A third portion of the four-and-seventy houses burned or fell to the ground, and another third were deserted by their tenants, who departed for more peaceful climes. Thus was the joyful tenor of life much diminished in this place; the lands lay fallow, the number of livestock about the houses did likewise decline. As we prepared for our first night there, my grandson Kornél asked, in German: Would it not be better at home? These were words we would oft repeat thereafter.

Thus began Grandpa Czuczor’s story in the canvas-bound folio he was given by his daughter Zsuzsánna. Excellent though his spoken knowledge was of German, Slovak, and Hungarian, he had so far written only in German. Having returned to the lands of the Magyar, he wanted to keep the story of their days in his mother tongue, perhaps because he wanted his grandson Kornél to read it when he grew up. The three of them had arrived by cart from Bavaria, whither Grandpa Czuczor and his brother had fled when the dust had settled over what was called, after its chief instigator, the Wesselényi conspiracy. Though the Czuczor brothers were strenuous in their denial of any involvement with the conspirators, some forgeries came to light, which sealed their fate: their assets were confiscated and even worse might have followed had they not hastily fled. Over the border they soon acquired skills as typographers and compositors, and established a printing press, later making their mark as bookbinders as well. In the guildhall of Thüningen their names were posted as the Gebrüder Czuczur.

Grandpa Czuczor never felt entirely at home in the windswept and rain-sodden lands of the beer-swilling Bavarians, whom in some obscure way he held responsible for the series of deaths that befell his family. Little wonder, then, that when he got wind of the Prince Primus’s patent, he went running to the printing press, where his brother was working on the leads. “We can pack our bags!” he yelled from the steps of the workshop. He pointed excitedly to his crumpled copy of the Mercurius Hungaricus, where a Latin text announced that a return to the de-populated villages of Hungary was now permitted without penalty.

No words of mine could win over my brother to the idea of going home with us. He preferred the comforts of Thüningen, newly acquired but at no small cost, where he wanted to pursue the crafts of printing and binding books. No news of him since that time. Zsuzsánna is troubled by the condition of little Kornél, her son, only in his fourth year of life, who in these straitened times suffers greatly from hunger, in want of meat and even eggs.

Returning by a circuitous route, they set up home in a house with a courtyard, put at their disposal at the edge of the village of Kos. Grandpa Czuczor immediately dug a hole at the bottom of the garden, by the rose bushes, and buried his money there, taking particular care not to inform either his grandson or his daughter of its whereabouts. Only Wilhelm, the servant they brought with them from Thüningen, knew of it, as he had helped with the digging.

“Wilhelm, du mußt das nie erzählen, verstehst du mich?” he warned Wilhelm, with an unambiguous gesture: drawing the edge of his palm across the front of his neck.

“ Jawohl! ” yelped the startled lad, as he did at every request or order. All he could manage in Hungarian was a fractured Janapat, “Good day!”

Kornél endured much taunting by the other boys for his thin, straw-colored hair, his oversized, floppy ears, and for the odd German word he would suddenly come out with. He picked up Hungarian quickly, even though these were not peaceful times conducive to study. Indeed, there was ominous news from every quarter.

The scrawny little boy was always hungry, yet never joined the noisy band of village youngsters who, despite a strict parental curfew, spent their days crisscrossing the fields and the forests, stripping them of anything remotely edible. Kornél preferred the company of his grandfather and would sit for hours in the yard where Grandpa Czuczor kept the printing paraphernalia he had brought back home. Kornél would try to make himself useful, but this generally turned out badly, as neither as a child nor later in life was he particularly good with his hands. The blind leading the lame, thought Grandpa Czuczor, as his own ten little servants became ever more spindly and twisted, and acquired an ever more troubling tremor. He had let one of his thumbnails grow into a long, sharp implement that he used for prising type out of its storage boxes; nowadays, try as he might to take care, this nail would split lengthwise and would serve only to scratch his head.

“Off you go, play with your little friends!”

The boy did not move. “I’d rather you told me a story!”

Grandpa Czuczor gave a sigh but was not unhappy to launch into one of his tales. “Do you know how my dear late father, Szaniszló Czuczor of Felsöfenyves, was granted his patent of nobility by György Rákóczi I, for outstanding bravery in the Vienna campaign?”

“I do! Tell me about Mother, when Mother was small! And about Mother’s mother!”

Grandpa Czuczor shook his head. It still ached often. In Thüningen he had married a smart and houseproud German woman. Hard-working but undemonstrative, Gisella had borne him six children, of whom all but the last, Zsuzsánna, the Lord had been pleased to take back unto Himself soon after their birth. The births had taken their toll on Gisella and it was not long before she, too, succumbed and joined her five little ones by the side of the Lord. Grandpa Czuczor’s hair turned white when she died, and every morning he would clutch the bony little body of the three-year-old Zsuzsánna desperately to his bosom: “May it please the Lord to let me keep you, my one and only!”

The girl would blink in surprise: “Was ist das, Vati?” She did not yet know Hungarian.

“Ach, du mußt mir bleiben, Liebchen!” he replied.

*

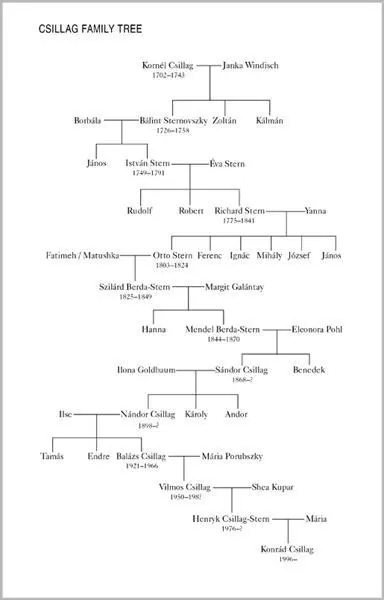

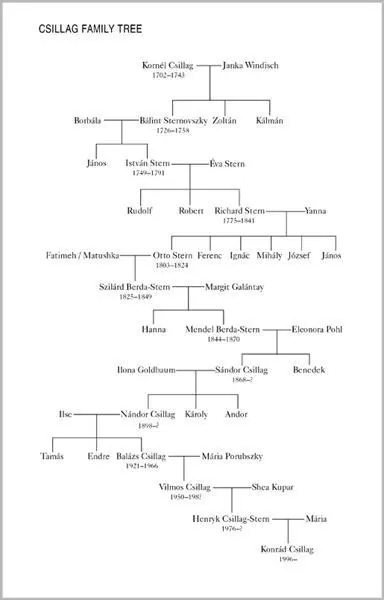

Zsuzsánna grew into a tall and slim young woman, and in due course married Péter Csillag, the son of another family that had chosen to return. Péter Csillag was granted the joys of married life for less than six months: he was out hunting when he was thrown by his horse and fell so awkwardly that he hit his head on a tree-stump and never recovered consciousness. After two weeks hovering between life and death, he expired.

“Grandpa! Why won’t you tell me a story?”

So he began to tell a very old story, which he had himself heard in his childhood. Kornél’s great-great-grandfather, Boldizsár Czuczor, was a skillful painter, a portraitist without compare in his time.

Читать дальше