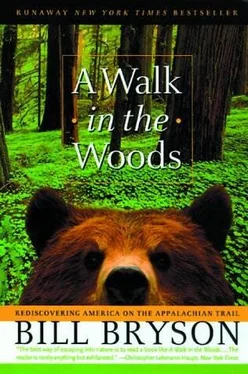

Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Walk In The Woods

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Walk In The Woods: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Walk In The Woods»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Walk In The Woods — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Walk In The Woods», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Appalachian Trail is the hardest thing I have ever done, and the Maine portion was the hardest part of the Appalachian Trail, and by a factor I couldn’t begin to compute. Partly it was the heat. Maine, that most moderate of states, was having a killer heat wave. In the blistering sun, the shadeless granite pavements of Moxie Bald radiated an ovenlike heat, but even in the woods the air was oppressive and close, as if the trees and foliage were breathing on us with a hot, vegetative breath. We sweated helplessly, copiously, and drank unusual quantities of water, but could never stop being thirsty. Water was sometimes plentiful but more often nonexistent for long stretches so that we were never sure how much we could prudently swallow without leaving ourselves short later on. Even fully stocked, we were short now thanks to Katz’s dumping a bottle. Finally, there were the relentless insects, the unsettling sense of isolation, and the ever-taxing terrain.

Katz responded to this in a way that I had never seen from him. He showed a kind of fixated resolve, as if the only way to deal with this problem was to bull through it and get it over with.

The next morning we came very early to the first of several rivers we would have to ford. It was called Bald Mountain Stream, but in fact it was a river-broad, lively, strewn with boulders. It was exceedingly fetching-it glittered with dancing spangles in the early morning sun and was gorgeously clear-but the current seemed strong and there was no telling from the shore how deep it might be in the middle. Several large streams in the area, my Appalachian Trail Guide to Maine noted blithely, “can be difficult or dangerous to cross in high water.” I decided not to share this with Katz.

We took off our shoes and socks, rolled up our pants, and stepped gingerly out into the frigid water. The stones on the bottom were all shapes and sizes-flat, egg-shaped, domed-very hard on the feet, and covered with a filmy green slime that was ludicrously slippery. I hadn’t gone three steps when my feet skated and I fell painfully on my ass. I struggled halfway to my feet but slipped and fell again; struggled up, staggered sideways a yard or two, and pitched helplessly forward, breaking my fall with my hands and ending up in the water doggie style. As I landed, my pack slid forward and my boots, tied to its frame by their laces, were hurled into a kind of contained orbit; they came around the side of the pack in a long, rather pretty trajectory, and came to a halt against my head, then plunked into the water, where they dangled in the current. As I crouched there, breathing evenly and telling myself that one day this would be a memory, two young guys-clones almost of the two we had seen the day before-strode past with confident, splashing steps, packs above their heads.

“Fall down?” said one brightly.

“No, I just wanted a closer look at the water.” You moronic fit twit.

I went back to the riverbank, pulled on my soaked boots, and discovered that it was infinitely easier crossing with them on. I got a tolerable grip and the rocks didn’t hurt as they had on my bare feet. I crossed cautiously, alarmed at the force of the current in the center-each time I lifted a leg the current tried to reposition it downstream, as if it belonged to a gateleg table-but the water was never more than about three feet deep, and I reached the other side without falling.

Katz, meantime, had discovered a way across using boulders as stepping stones but ended up stranded on the edge of a noisy torrent of what looked like deep water. He stood there covered with frowns. I couldn’t for the life of me figure out how he had gotten up there-his boulder seemed isolated in an expanse of dangerously streaming water from all sides, and clearly he didn’t Know what to do now. He tried to ease himself into the silvery current and wade the last ten yards to shore but was instantly whisked away like a feather. For the second time in two days I sincerely thought he was drowning-he was certainly helpless-but the current carried him to a shallow bar of gleaming pebble twenty feet farther on, where he came up sputtering on his hands and knees, struggled up on to the bank, and continued on into the woods without a backward glance, as if this were the most normal thing in the world.

And so we pressed on to Monson, over hard trail and more rivers, collecting bruises and scratches and insect bites that turned our backs into relief maps. On the third day, forest-dazed and grubby, we stepped on to a sunny road, the first since Caratunk, and followed it on a hot ambulation into the forgotten hamlet of Monson. Near the center of town was an old clapboard house with a painted wooden cutout of a bearded hiker standing on the lawn bearing the message “Welcome at Shaw’s.”

Shaw’s is the most famous guesthouse on the AT, partly because it’s the last comfort stop for anyone going into the Hundred Mile Wilderness and the first for anyone coming out, but also because it’s very friendly and a good deal. For $28 each we got a room, dinner and breakfast, and free use of the shower, laundry, and guest lounge. The place was run by Keith and Pat Shaw, who started the business more or less by accident twenty years ago when Keith brought home a hungry hiker off the trail and the hiker passed on the word of how well he had been treated. Just a few weeks earlier, Keith told me proudly as we signed in, they had registered their 20,000th hiker.

We had an hour till dinner. Katz borrowed $5-for pop, I presumed-and vanished to his room. I had a shower, put a load or wash in the machine, and wandered out to the front lawn, where there were a couple of Adirondack chairs on which I intended to park my weary butt, smoke my pipe and savor the blissful ease or late afternoon and the pleasant anticipation of a dinner earned. From a screened window nearby came the sounds of sizzling food and the clatter of pans. It smelled good, whatever it was.

After a minute, Keith came out and sat with me. He was an old guy, comfortably into his sixties, with almost no teeth and a body that looked as if it had put up with all kinds of tough stuff in its day. He was real friendly.

“You didn’t try to pet the dog, did ya?” he said.

“No.” I had seen it out the window: an ugly, vicious mongrel that was tied up out back and got stupidly and disproportionately worked up by any noise or movement within a hundred yards.

“You don’t wanna try to pet the dog. Take it from me: you do not wanna pet that dog. Some hiker petted him last week when I told him not to and it bit him in the balls.”

“Really?”

He nodded. “Wouldn’t let go neither. You shoulda heard that feller wail.”

“Really?”

“Had to hit the damn dog with a rake to get him to let go. Meanest damn dog I ever seen in my life. You don’t wanna get near him, believe me.”

“How was the hiker?”

“Well, it didn’t exactly make his day, I tell you that.” He scratched his neck contemplatively, as if he were thinking of having a shave one of these days. “Thru-hiker, he was. Come all the way from Georgia. Long way to come to get your balls nipped.” Then he went off to check on dinner.

Dinner was at a big dining room table that was generously covered in platters of meat, bowls of mashed potatoes and corn on the cob, a teetering plate of bread, and a tub of butter. Katz arrived a few moments after me, looking freshly showered and very happy. He seemed unusually, almost exaggeratedly, energized, and gave me an impetuous tickle from behind as he passed, which was out of character.

“You all right?” I said.

“Never been better, my old mountain companion, never been better.”

We were joined by two others, a sweetly hesitant and wholesome-looking young couple, both tanned and fit and also very clean. Katz and I welcomed them with smiles and started to pitch in, then paused and put back the bowls when we realized the couple were mumbling grace. This seemed to go on forever. The we pitched in again.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Walk In The Woods» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.