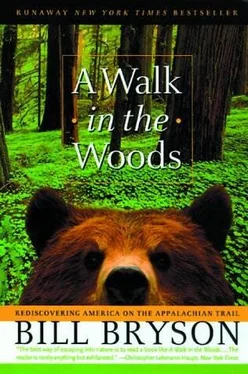

Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Bill Bryson - A Walk In The Woods» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Walk In The Woods

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Walk In The Woods: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Walk In The Woods»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Walk In The Woods — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Walk In The Woods», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Everyone has a supremely low moment somewhere along the AT, usually when the urge to quit the trail becomes almost overpowering. The irony of my moment was that I wanted to get back on the trail and didn’t know how. I hadn’t lost just Katz, my boon companion, but my whole sense of connectedness to the trail. I had lost my momentum, my feeling of purpose. In the most literal way I needed to find my feet again. And now on top of everything else I was quaking as if I had never been out in the woods before. All the experience I had piled up in the earlier weeks seemed to make it harder rather than easier to be out on the trail on my own. I hadn’t expected this. It didn’t seem fair. It certainly wasn’t right. In a glum frame of mind, I returned to the car.

I spent the night near Harrisburg and in the morning drove north and east across the state on back highways, trying to follow the trail as closely as I could by road, stopping from time to time where possible to sample the trail but without finding anything remotely rewarding, so mostly I drove.

Little by little the town names along the way began to take on a frank industrial tone-Port Carbon, Minersville, Slatedale-and I realized I was entering the strange, half-forgotten world of Pennsylvania ’s anthracite region. At Minersville, I turned onto a back highway and headed through a landscape of overgrown mine tailings and rusting machinery towards Centralia, the strangest, saddest town I believe I have ever seen.

Eastern Pennsylvania sits on one of the richest coal beds on earth. Almost from the moment Europeans arrived, they realized there was coal out there in quantities almost beyond conception. The trouble was, it was virtually all anthracite, a coal so immensely hard (it is 95 percent carbon) that for a very long time no one could figure out how to get it to light. It wasn’t until 1828 that an enterprising Scot named James Neilson had the simple but effective idea of injecting heated air rather than cold air into an iron furnace by means of a bellows. The process became known as a hot blast, and it transformed the coal industry all over the world (Wales, too, had a lot of anthracite) but especially in the United States. By the end of the century America was producing 300 million tons of coal a year, about as much as the rest of the world put together, and the great bulk of it came from Pennsylvania ’s anthracite belt.

Meanwhile, to its intense gratification, Pennsylvania had also discovered oil-not only discovered it but devised ways to make it industrially useful. Petroleum (or rock oil) had been a curiosity of western Pennsylvania for years. It emerged in seeps along riverbanks, where it was blotted up with blankets to be made into patent medicines esteemed for their value to cure everything from scrofula to diarrhea. In 1859, a mysterious figure named Col. Edwin Drake (who wasn’t a colonel at all but a retired railway conductor, with no understanding of geology) developed, from goodness knows where, the belief that oil could be extracted from the ground via wells. At Titusville, he bored a hole to a depth of sixty-nine feet and got the world’s first gusher. Quickly it was realized that petroleum in volume not only could be used to bind bowels and banish scabby growths but could be refined into lucrative products like paraffin and kerosene. Western Pennsylvania boomed inordinately. In three months, as John McPhee notes in In Suspect Terrain, the endearingly named Pithole City went from a population of zero to 15,000, and other towns throughout the region sprang up- Oil City, Petroleum Center, Red Hot. John Wilkes Booth came and lost his savings, then went off to kill a president, but others stayed and made a fortune.

For one lively half century Pennsylvania had a virtual monopoly on one of the most valuable products in the world, oil, and an overwhelmingly dominant role in the production of a second, coal. Because of the proximity of rich supplies of fuel, the state became e center of big, fuel-intensive industries like steelmaking and chemicals. Lots of people became colossally rich.

But not the mineworkers. Mining has of course always been a wretched line of work everywhere, but nowhere more so than in the United States in the second half of the nineteenth century. Thanks to immigration, miners were infinitely expendable. When the Welsh got belligerent, you brought in Irish. When they failed to satisfy, you brought in Italians or Poles or Hungarians. Workers were paid by the ton, which both enouraged them to hack out coal with reckless haste and meant that any labor they expended making their environment safer or more comfortable went uncompensated. Mine shafts were bored through the earth like holes through Swiss cheese, often destabilizing whole valleys. In 1846 at Carbondale almost fifty acres of mine shafts collapsed simultaneously without warning, claiming hundreds of lives. Explosions and flash fires were common. Between 1870 and the outbreak of the First World War, 50,000 people died in American mines.

The great irony of anthracite is that, tough as it is to light, once you get it lit it’s nearly impossible to put out. Stories of uncontrolled mine fires are legion in eastern Pennsylvania. One fire at Lehigh started in 1850 and didn’t burn itself out until the Great Depression-eighty years after it started.

And thus we come to Centralia. For a century, Centralia was a sturdy little pit community. However difficult life may have been for the early miners, by the second half of the twentieth century Centralia was a reasonably prosperous, snug, hardworking town with a population approaching 2,000. It had a thriving business district, with banks and a post office and the normal range of shops and small department stores, a high school, four churches, an Odd Fellows Club, a town hall-in short, a typical, pleasant, contentedly anonymous small American town.

Unfortunately, it also sat on twenty-four million tons of anthracite. In 1962, a fire in a dump on the edge of town ignited a coal seam. The fire department poured thousands of gallons of water on the fire, but each time they seemed to have it extinguished it came back, like those trick birthday candles that go out for a moment and then spontaneously reignite. And then, very slowly, the fire began to eat its way along the subterranean seams. Smoke began to rise eerily from the ground over a wide area, like steam off a lake at dawn. On Highway 61, the pavement grew warm to the touch, then began to crack and settle, rendering the road unusable. The smoking zone passed under the highway and fanned out through a neighboring woodland and up towards St. Ignatius Catholic church on a knoll above the town.

The U.S. Bureau of Mines brought in experts, who proposed any number of possible remedies-digging a deep trench through the town, deflecting the course of the fire with explosives, flushing the whole thing out hydraulically-but the cheapest proposal would have cost at least $20 million, with no guarantee that it would work, and in any case no one was empowered to spend that kind of money. So the fire slowly burned on.

In 1979, the owner of a gas station near the center of town found that the temperature in his underground tanks was registering 172°F. Sensors sunk into the earth showed that the temperature thirteen feet under the tanks was almost 1,000°. Elsewhere, people were discovering that their cellar walls and floors were hot to the touch. By now smoke was seeping from the ground all over town, and people were beginning to grow nauseated and faint from the increased levels of carbon dioxide in their homes. In 1981, a twelve-year-old boy was playing in his grandmother’s backyard when a plume of smoke appeared in front of him. As he stared at it, the ground suddenly opened around him. He clung to tree roots until someone heard his calls and hauled him out. The hole was found to be eighty feet deep. Within days, similar cave-ins were appearing all over town. It was about then that people started getting serious about the fire.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Walk In The Woods» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Walk In The Woods» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.