“Heinous fuckery most foul, lad. Heinous fuckery most foul.”

“Aye, that’s the dog’s bollocks, [12] The dog’s bollocks! — excellent! The bee’s knees! The cat’s pj’s. Literally, the dog’s balls, which doesn’t seem to be that great a thing, yet, there you are.

then!” said Drool, slapping his thigh. “Did you hear, Mary? Heinous fuckery afoot. Ain’t that the dog’s bollocks?”

“Oh yeah, the dog’s bloody B. it is, love. If the saints are smilin’ on us, maybe one of them nobles will hang your wee mate there like they been threatening.”

“Two fools well-hung we’d have then, wouldn’t we?” said I, elbowing my apprentice in the ribs.

“Aye, two fools well-hung, we’d have, wouldn’t we?” said Drool, in my voice, tone to note coming out his great maw as like he’d caught an echo on his tongue and coughed it right back. That’s the oaf’s gift—not only can he mimic perfectly, he can recall whole conversations, hours long, recite them back to you in the original speakers’ voices, and not comprehend a single word. He’d first been gifted to Lear by a Spanish duke because of his torrential dribbling and the ability to break wind that could darken a room, but when I discovered the Natural’s keener talent, I took him as my apprentice to teach him the manly art of mirth.

Drool laughed. “Two fools well-hung—”

“Stop that!” I said. “It’s unsettling.” Unsettling indeed, to hear your own voice sluicing pitch-perfect out of that mountain of lout, stripped of wit and washed of irony. Two years I’d had Drool under my wing and I was still not inured to it. He meant no harm, it was simply his nature.

The anchoress at the abbey had taught me of nature, making me recite Aristotle: “It is the mark of an educated man, and a tribute to his culture, that he look for precision in a thing only as its nature allows.” I would not have Drool reading Cicero or crafting clever riddles, but under my tutelage he had become more than fair at tumbling and juggling, could belch a song, and was, at court, at least as entertaining as a trained bear, with slightly less proclivity for eating the guests. With guidance, he would make a proper fool.

“Pocket is sad,” said Drool. He patted my head, which was wildly irritating, not only because we were face-to-face—me standing, him sitting bum-to-floor—but because it rang the bells of my coxcomb in a most melancholy manner.

“I’m not sad,” said I. “I’m angry that you’ve been lost all morning.”

“I weren’t lost. I were right here, the whole time, having three laughs with Mary.”

“Three?! You’re lucky you two didn’t burst into flames, you from friction and her from bloody thunderbolts of Jesus.”

“Maybe four,” said Drool.

“You do look the lost one, Pocket,” said Mary. “Face like a mourning orphan what’s been dumped in the gutter with the chamber pots.”

“I’m preoccupied. The king has kept no company but Kent this last week, the castle is brimming with backstabbers, and there’s a girl-ghost rhyming ominous on the battlements.”

“Well, there’s always a bloody ghost, ain’t there?” Mary fished a shirt out of the cauldron and bobbed it across the room on her paddle like she was out for a stroll with her own sodden, steaming ghost. “You’ve got no cares but making everyone laugh, right?”

“Aye, carefree as a breeze. Leave that water when you’re done, would you, Mary? Drool needs a dunking.”

“Nooooooo!”

“Hush, you can’t go before the court like that, you smell of shit. Did you sleep on the dung heap again last night?”

“It were warm.”

I clouted him a good one on the crown with Jones. “Warm’s not all, lad. If you want warm you can sleep in the great hall with everyone else.”

“He ain’t allowed,” offered Mary. “Chamberlain [13] Chamberlain—a servant usually in charge of running a castle or household.

says his snoring frightens the dogs.”

“Not allowed?” Every commoner who didn’t have quarters slept on the floor in the great hall—strewn about willy-nilly on the straw and rushes—nearly dog-piled before the fireplace in winter. An enterprising fellow with night horns aloft and a predisposal to creep might find himself accidentally sharing a blanket or a tumble with a sleepy and possibly willing wench, and then be banished for a fortnight from the hall’s friendly warmth (and indeed, I owe my own modest apartment above the barbican [14] Barbican—a gatehouse, or extension of a castle wall beyond the gatehouse, used for defense of the main gate, often connected to a drawbridge.

to such nocturnal proclivity), but put out for snoring? Unheard of. When night’s inky cape falls o’er the great hall, a gristmill it becomes, the machines of men’s breath grind their dreams with a frightful roar, and even Drool’s great gears fall undistinguished among the chorus. “For snoring? Not allowed in the hall? Balderdash!”

“And for having a wee on the steward’s wife,” Mary added.

“It were dark,” explained Drool.

“Aye, and even in daylight she is easily mistaken for a privy, but have I not tutored you in the control of your fluids, lad?”

“Aye, and with great success,” said Shanker Mary, rolling her eyes at the spunk-frosted wall.

“Ah, Mary, well said. Let’s make a pact: If you do not make attempts at wit, I will refrain from becoming a soap-smelling prick-pull. What say ye?”

“You said you liked the smell of soap.”

“Aye, well, speaking of smell. Drool, fetch some buckets of cold water from the well. We need to cool this kettle down and get you bathed.”

“Nooooooo!”

“Jones will be very unhappy with you if you don’t hurry,” said I, brandishing Jones in a disapproving and somewhat threatening manner. A hard master is Jones, bitter, no doubt, from being raised as a puppet on a stick.

A half-hour later, a miserable Drool sat in the steaming cauldron, fully-clothed, his natural broth having turned the lye-white water to a rich, brown oaf-sauce. Shanker Mary stirred about him with her paddle, being careful not to stir him beyond suds to lust. I was quizzing my student on the coming night’s entertainments.

“So, because Cornwall is on the sea, we shall portray the duke how, dear Drool?”

“As a sheep-shagger,” said the despondent giant.

“No, lad, that’s Albany. Cornwall shall be the fish-fucker.”

“Aye, sorry, Pocket.”

“Not a worry, not a worry. You’ll still be sodden from your bath, I suspect, so we’ll work that into the jest. Bit of sloshing and squishing will but add to the merriment, and if we can thus imply that Princess Regan is herself, a fishlike consort, well I can’t think of anyone who won’t be amused.”

“’Cepting the princess,” said Mary.

“Well, yes, but she is very literal-minded and often has to be explained the thrust of the jest a time or two before lending her appreciation.”

“Aye, remedial thrusting’s the remedy for Regan’s stubborn wit,” said the puppet Jones.

“Aye, remedial thrusting’s the remedy for Regan’s stubborn wit,” said Drool in Jones’s voice.

“You’re dead men,” sighed Shanker Mary.

“You’re a dead man, knave!” said a man’s voice from behind me.

And there stood Edmund, bastard son of Gloucester, blocking the only exit, sword in hand. Dressed all in black, was the bastard: a simple silver brooch secured his cape, the hilts of his sword and dagger were silver dragon heads with emerald eyes. His jet beard was trimmed to points. I do admire the bastard’s sense of style—simple, elegant, and evil. He owns his darkness.

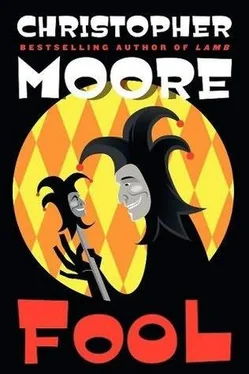

I, myself, am called the Black Fool. Not because I am a Moor, although I hold no grudge toward them (Moors are said to be talented wife-stranglers) and would take no offense at the moniker were that the case, but my skin is as snowy as any sun-starved son of England. No, I am called so because of my wardrobe, an argyle of black satin and velvet diamonds—not the rainbow motley of the run-a-day fool. Lear said: “After thy black wit shall be thy dress, fool. Perhaps a new outfit will stop you tweaking Death’s nose. I’m short for the grave as it is, boy, no need to anger the worms before my arrival.” When even a king fears irony’s twisted blade, what fool is ever unarmed?

Читать дальше