“Speak plain, Pocket, I’ll not hold harm against you.”

“You needed to smack the bitch up when she was tender, my lord. Instead, now you hand your daughters the rod and pull down your own breeches.”

“I’ll have you flogged, fool.”

“His word is like the dew,” said the puppet Jones, “good only until put under light of day.”

I laughed, simple fool that I am, no thought at all that Lear was becoming as inconstant as a butterfly. “I need to speak to Curan and find a horse for the journey, sirrah,” said I. “I’ll bring your cloak.”

Lear sagged in the saddle now, spent now from his ranting. “Go, good Pocket. Have my knights prepare.”

“So I shall,” said I. “So I shall.” I left the old man there alone outside the castle.

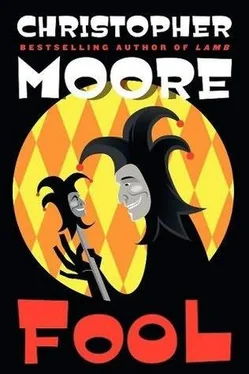

Having set the course of events in motion, I wonder now if my training to be a nun, and my polished skills at telling jokes, juggling, and singing songs fully qualify me to start a war. I have so often been the instrument of the whims of others, not even a pawn at court, merely an accoutrement to the king or his daughters. An amusing ornament. A tiny reminder of conscience and humanity, tempered with enough humor so it can be dismissed, laughed off, ignored. Perhaps there is a reason that there is no fool piece on the chessboard. What action, a fool? What strategy, a fool? What use, a fool? Ah, but a fool resides in a deck of cards, a joker, sometimes two. Of no worth, of course. No real purpose. The appearance of a trump, but none of the power. Simply an instrument of chance. Only a dealer may give value to the joker. Make him wild, make him trump. Is the dealer Fate? God? The king? A ghost? Witches?

The anchoress spoke of the cards in the tarot, forbidden and pagan as they were. We had no cards, but she would describe them for me, and I drew their images on the stones of the antechamber in charcoal. “The fool’s number is zero,” she said, “but that’s because he represents the infinite possibility of all things. He may become anything. See, he carries all of his possessions in a bundle on his back. He is ready for anything, to go anywhere, to become whatever he needs to be. Don’t count out the fool, Pocket, simply because his number is zero.”

Did she know where I was heading, or do her words only have meaning to me now, as I, the zero, the nothing, seek to move nations? War? I couldn’t see the appeal.

Drunk, and dire of mood one night, Lear mused of war when I suggested that what he needed to cast off his dark aspect was a good wenching. “Oh, Pocket, I am too old, and the joy of a fuck withers with my limbs. Only a good killing can still boil lust in my blood. And one will not do, either. Kill me a hundred, a thousand, ten thousand on my command—rivers of blood running through the fields—that’s what pumps fire into a man’s lance.”

“Oh,” said I. “I was going to fetch Shanker Mary for you from the laundry, but ten thousand dead and rivers of blood might be a bit beyond her talents, majesty.”

“No, thank you, good Pocket, I shall sit and slide slowly and sadly into oblivion.”

“Or,” said I, “I could put a bucket on Drool’s head and beat him with a sack of beets until the floor is splattered crimson while Shanker Mary gives you a proper tug to accentuate the gore.”

“No, fool, there is no pretending to war.”

“What’s Wales doing, majesty? We could invade the Welsh, perpetrate enough slaughter to raise your spirits, and have you back for tea and toast.”

“Wales is ours now, lad.”

“Oh bugger. What’s your feeling on attacking North Kensington, then?”

“Kensington’s not a mile away. Practically in our own bailey.”

“Aye, nuncle, that’s the beauty of it, they’d never see it coming. Like a hot blade through butter, we’d be. We could hear the widows and orphans wailing from the castle walls—like a horny lullaby for you.”

“I should think not. I’m not attacking neighborhoods of London to amuse myself, Pocket. What kind of tyrant do you think me?”

“Oh, above average, sire. Well above bloody average.”

“I’ll have you speak no more of war, fool. You’ve too sweet a nature for such dastardly pursuits.”

Too sweet? Moi? Methinks the art of war was made for fools, and fools for war. Kensington trembled that night.

On the road to Gloucester I let my anger wane and tried to comfort the old king as best I could by lending him a sympathetic ear and a gentle word when he needed it.

“You simple, sniveling old toss-beast! What did you expect to happen when you put the care of your half-rotted carcass in the talons of that carrion bird of a daughter?” (I may have had some residual anger.)

“But I gave her half my kingdom.”

“And she gave you half the truth in return, when she told you she loved you all.”

The old man hung his head and his white hair fell in his face. We sat on stones by the fire. A tent was set in the wood nearby for the king’s comfort, as there was no manor house in this northern county for him to take refuge. The rest of us would sleep outside in the cold.

“Wait, fool, until we are under the roof of my second daughter,” said Lear. “Regan was always the sweet one, she will not be so shabby in her gratitude.”

I had no heart to chide the old man any more. Expecting kindness from Regan was hope sung in the key of madness. Always the sweet one? Regan? I think not.

My second week in the castle I found young Regan and Goneril in one of the king’s solars, teasing little Cordelia, passing a kitten the little one had taken a fancy to over her head, taunting her.

“Oh, come get the kitty,” said Regan. “Be careful, lest it fly out the window.” Regan pretended she might throw the terrified little cat out the window, and as Cordelia ran, arms stretched out to grab the kitten, Regan reeled and tossed the kitten to Goneril, who swung the kitten toward another window.

“Oh, look, Cordy, she’ll be drowned in the moat, just like your traitor mother,” said Goneril.

“Nooooooo!” wailed Cordelia. She was nearly breathless from running sister to sister after the kitten.

I stood in the doorway, stunned at their cruelty. The chamberlain had told me that Cordelia’s mother, Lear’s third queen, had been accused of treason and banished three years before. No one knew exactly the circumstances of the crime, but there were rumors that she had been practicing the old religion, others that she had committed adultery. All the chamberlain knew for sure was that the queen had been taken from the tower in the dead of night, and from that time until my arrival at the castle, Cordelia had not uttered a coherent syllable.

“Drowned as a witch, she was,” said Regan, snatching the kitten out of the air. But this time the little kitten’s claws found royal flesh. “Ow! You little shit!” Regan tossed the kitten out the window. Cordelia loosed an ear-shattering scream.

Without thinking I dived through the window after the cat and caught the braided cord with my feet as I flew through. I caught the kitten about five feet below the window as the cord burned between my ankles. Not having thought the move completely through, I hadn’t counted on how to catch myself, kitten in hand, when the cord slammed me into the tower wall. The cord tightened around my right ankle. I took the impact on that shoulder and bounced while I watched my coxcomb flutter like a wounded bird to the moat below.

I tucked the kitten into my doublet, then climbed back up the cord and in through the window. “Lovely day for a constitutional, don’t you think, ladies?”

The three of them all stood with their mouths hanging open, the older sisters had backed against the walls of the solar. “You lot look like you could use some air,” said I.

Читать дальше