They knocked on his door once or twice a day. Each time, Robert stood motionless, interrupted at his desk, or during his dinner; he could hear them speaking softly to each other in the hall. Just open the door, he told himself. Don’t be such a wanker.

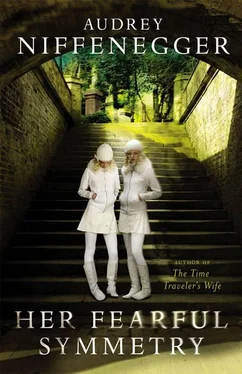

He hesitated before their twinness; they seemed sublime and inviolable together. Each morning he watched them navigating the slippery path to the gate. They appeared so self-sufficient, and conversely so reliant on each other, that he felt rejected without having ever exchanged a word with either of them.

One bright chilly morning Robert stood at his front window, coffee in hand, wearing his coat and hat, waiting. Eventually he heard the twins galumphing down the stairs. He watched them cross the yard and let themselves out of the gate.

Then he followed them.

They led him across Pond Square, through Highgate Village and along Jackson’s Lane to the Highgate tube station. He hung back, let them disappear, then panicked that a train might come and whisk them off. He ran down the escalator. The station was nearly deserted, it was half eleven. He found them again on the southbound platform, positioned himself just close enough to get into the same carriage. They sat near the middle doors. He sat across from them, fifteen feet away. One twin studied a pocket tube map. The other leaned back in her seat and studied the adverts. “Look,” she said to her sister, “we could fly to Transylvania for a pound each.” Robert was startled to hear her soft American accent, so different from Elspeth’s confident Oxbridge voice.

He avoided looking at them. He thought of a cat his mum had, Squeak; every time they took it to the vet’s surgery, the cat tucked its head under Robert’s arm and hid. She seemed to think that if she couldn’t see the vet, the vet couldn’t see her. Robert did not look at the twins, so they would not see him.

They got off at Embankment and changed for the District line. Eventually they emerged from Sloane Square station and wandered haltingly into Belgravia, stopping often to consult their A-Z . Robert never came to this part of London, so he, too, became quickly lost. He hung back, keeping his eye on them and feeling pervy and gormless, not to mention highly noticeable. Smart young Sloanes of both sexes marched past him, toting inscrutable shopping bags, mobiles clamped to their ears. Little fogs of breath emanated from their mouths as they rushed by, chatting to themselves like actors rehearsing. The twins seemed tentative and childish by comparison.

They wandered into a side street and became suddenly excited, skipping along and craning their necks at the shop numbers. “Here!” said one. They went into a tiny hat shop, Philip Treacy, and spent an hour trying on hats. Robert watched them from across the street. The twins took turns with the hats, turning in front of what must have been a mirror. The shopgirl smiled at them and offered an enormous lime-green spiral. A twin put it on her head and all three of them looked quite pleased.

Robert wished that he smoked, as it would have provided an excuse to stand about in the street looking pointless. Maybe I should go and have a pint. They look as though they’ll be at this all afternoon. The twins were exclaiming over a plastic orange disc that reminded Robert of the dinner-plate-like halos in medieval paintings. I need a disguise. Maybe a beard. Or a hazmat suit. The twins came out of the shop without any bags.

Robert trailed them all over Knightsbridge, watching them window-shop, eat crepes, gawk at other shoppers. Midafternoon they vanished into the underground. Robert let them go and took himself to the British Library.

He put his things in a locker and went upstairs to the Humanities 1 reading room. The room was crowded and he found a seat between a beaky woman surrounded by books about Christopher Wren and a hirsute young man who seemed to be researching Jacobite housekeeping practices. Robert did not order any books; he didn’t even check on the books he had previously ordered. He put both palms flat on the desk top and closed his eyes. I feel odd. He wondered if he was coming down with the flu. Robert was aware of a split within himself-he was filled with contradictory emotions, some of which included shame, exhilaration, accomplishment, confusion, disgust with himself and a strong desire to follow the twins again tomorrow. He opened his eyes and tried to pull himself together. You can’t spy on them like this. They’ll notice sooner or later. Robert imagined Elspeth chiding him: “Don’t be gutless, sweet. Just open the door the next time they knock.” Then he thought she would have laughed at him. Elspeth never understood shyness. Don’t laugh at me, Elspeth, Robert said to her in his mind. Don’t.

The call light at his desk lit up. Robert realised that he must be sitting in someone else’s seat. He glanced around, then got up and left the reading room. He took the tube home. As he walked down the path to Vautravers he saw lights in the windows of the middle flat, and his heart contracted in joy. Then he remembered it was only the twins. Today was a one-off. Tomorrow I’ll knock on their door and introduce myself properly.

The next morning he followed them to Baker Street and paid twenty quid to wander around Madame Tussauds at a discreet distance from the twins as they made fun of wax versions of Justin Timberlake and the Royal Family. The day after that they all went to the Tower and then took in a puppet show on the Embankment. Robert began to despair. Don’t you ever do anything interesting? Days passed in a blur of Neal’s Yard, Harrods, Buckingham Palace, Portobello Road, Westminster Abbey and Leicester Square. Robert sensed the twins’ determination: they seemed to be circling London’s most public spheres, looking for a rabbit hole into the real city underneath. They were trying to construct a personal London for themselves out of the Rough Guide and Time Out.

Robert had been born in Islington. He had never lived anywhere but London. His geography of London was a tangle of emotional associations. Street names evoked girlfriends, schoolmates, boring afternoons playing truant and doing nothing in particular; rare outings with his father to obscure restaurants and the zoo, raves in East-London warehouses. He began to pretend that the twins were taking him on school outings, that they were all three attending an exotic public school with odd uniforms and a curriculum of tourism. He stopped thinking about what he was doing, or worrying very much about being caught. Their obliviousness frightened him. They lacked the urban camouflage skills young women ought to have. People stared at them all the time, and they seemed to be aware of this without making very much of it, as though being the objects of constant attention was natural to them.

They led and he followed. He went to the cemetery intermittently. When Jessica asked, he told her he was working at home on his thesis. She looked at him curiously; later he noticed the messages piled up on his answering machine and understood that she thought he was avoiding her.

Then the twins stayed in several days running. One twin did little errands by herself. Robert worried. I should go up and check on them. By now he felt that he knew them well, but he had never spoken to them. He missed them. He berated himself for becoming immersed in their lives. Still, he hesitated to begin. He found himself spending whole days sitting quietly in his flat, listening, waiting, worrying.

V ALENTINA DIDN’T feel well that morning, so Julia went to the Tesco Express to buy chicken soup, Ritz crackers and Coke, which the twins considered to be the proper cuisine for invalids. As soon as Julia left, Valentina dragged herself out of bed, threw up in the toilet, went back to bed and lay on her side, knees pulled to her chest, burning with fever. She stared at the rug, tracing the gold-and-blue shapes with her eyes. She began to fall asleep.

Читать дальше