“Hey,” Ahmet says, shaking your forearm. “Are you all right? You’re making weird sounds.”

Weird sounds. That’s the best you could do—it wasn’t the scream you thought you needed, but it worked. The cockroaches scatter back to the little dream nests where they sit it out while you’re awake. You blink your eyes a few times, then pry them open with your fingers.

“Can we get some coffee?” you ask.

“If we stop for coffee now we’re going to have to stop three more times in the next hour so you can pee,” he says.

“I’ll get some adult diapers when we stop and just pee into those,” you say.

“I wish you would do that,” he says.

“I will,” you say. It scares you a little that you’re not really joking.

“What do you need coffee for, anyway? You’re not even the one driving.”

“I don’t want to keep falling asleep.”

Ahmet is white-knuckling the wheel. He’s getting annoyed, and you don’t blame him. You’re still groggy, but conscious enough to realize how annoying you’re being, annoying enough that you don’t want to hear yourself talk, only you can’t seem to stop babbling about cockroaches and the various forms of truck stop caffeine. You suddenly understand completely why NYU doesn’t want you, and why your father didn’t, and why some people want to punch you in the mouth, which knows only two modes: silent and this nonsense.

“You need sleep,” Ahmet says. “You said yourself how tired you are. You almost had a nervous breakdown in Walmart.”

“I don’t want to sleep this kind of sleep. I’m having bad dreams.”

“This whole thing is a bad dream,” he says.

“What?”

“Nothing.”

“I want to stop.”

“Please just go to sleep.”

“No, I want to stop. I don’t want to do this anymore,” you say. You didn’t expect those words to leave your mouth, but hearing them makes you feel like Einstein stumbling onto some new physics theorem, an answer to something that’s been sitting there all along, just waiting to be discovered. You want to stop. You want to stop! It sounds so perfect in your head that you repeat it again out loud. “I want to stop, Ahmet. Stop.”

But Ahmet’s foot is getting heavier on the go pedal, not the stop one.

“You don’t have to do this anymore, either. I don’t want you to do this for me.”

“It’s a little late for that. We’re closer to Houston than to Waterbury.”

“Just let me out,” you say.

“Just calm down,” he answers.

“I’m calm. Who’s not calm? I just don’t want to do this anymore.”

He shakes his head in disbelief. You could have told him you were a genie and he wouldn’t have been more confused. You could have told him that you were pregnant with his child and he wouldn’t have been more disgusted.

“And what do you want to do instead?” he asks.

You shake your head.

“What is even wrong with you?”

“I don’t know,” you say. The question was meant to be hypothetical at best, insulting at worst, but you like the question. It makes you feel like some progress is being made: you both acknowledge that there’s something wrong with you, which is strangely reassuring.

Ahmet doesn’t seem to take comfort in it. Even with his hands firmly gripping the wheel, you can see that he’s shaking, his Adam’s apple moving ever so slightly up and down as he swallows what might be sobs, at least if you’re willing to acknowledge that you could have caused another human being enough pain to cry. Sure, there’s power in that, in making someone cry, there’s that English-class agency word popping up in real-world practical applications again, and yet it doesn’t feel awesome like it had back in the assistant principal’s office, when it seemed like the key to forward momentum.

“I’m sorry,” you say.

“Your mother has no idea where you are, right?”

“Can you please pull over? Will you please stop the car?”

“You could just get up and leave? How do you do that? Don’t you have any feelings?”

“I do,” you say. “I feel sick. I think I’m going to throw up. Please pull over.”

“Is that why you want to be with him? Because you’re just like him?”

“Maybe,” you say. “I might be. I don’t know.”

“It’s cruel. You have been just cruel,” he says, and he seems as confused by your cruelty as saddened by it. This boy refugee, who has seen neighbors kill neighbors, who had been born into a war and lost more than you had ever known by the time he had been potty-trained; this young handsome man, who has managed to find joy in Kawasakis and hope in Panera Bread; this person is confused and saddened by you, who, he is just realizing, has silently mocked him for his Kawasaki and Panera Bread, and used him not for his company but for his hatchback. He who had been born into cruelty and yet somehow had not been ruined by it, and in fact had rejected it so entirely that he didn’t even recognize it in you when he met you, is now reminded that he should have never let his guard down, not even with someone whose face is as pretty as yours.

“There’s a rest stop at the next exit,” you say. “Please stop.”

He does stop. He stops talking and, in half a mile, he stops the car. He stops looking at you quizzically when you grab your bag from the backseat, and when you come back to tell him that you’ll be hitching a ride with a silver-headed woman who found you crying so pathetically that she felt obligated to offer you a ride in her camper with her and her old man, he doesn’t try to talk you out of it. He tells you obligatorily that it’s a bad idea, hands you a pair of brass knuckles from his glove box, and tells you to text him if you change your mind, but you know that he hopes you won’t. You can see that he’s already rebuilding, heading east back to the home he hadn’t chosen but had enough sense to treasure.

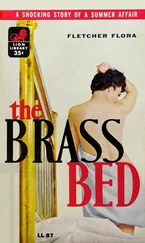

I came home from work and went to collapse onto the air mattress and found instead an actual mattress with an actual box spring sitting on an actual metal bed frame. It wasn’t made up—that was women’s work—but the sheets were ready at the foot, and a new comforter was waiting to be plucked from its plastic sack and made to live up to its name. It did, briefly. It was such a beautiful innerspring-and-latex oasis that I didn’t care if it turned out to be some rent-to-own wonder that might be repoed in the middle of the night. I just enveloped the mattress in the scratchy sheets, pulled the blanket up to my chin, and let myself be comforted straight into a deep, deep sleep. I woke up because I was starving, and the hunger was infiltrating my dream, in which I was standing in line at a Chinese restaurant but never able to quite make it to the buffet. I cried and flailed, but I never got my hands on any of the crab rangoons I needed to stay alive.

When I woke, Bashkim was looking at me like a prowler caught in the act.

“Do you like the bed?” he asked.

“It looks like I do,” I said. “What are you doing home?”

He walked over and sat down by my feet, knowing that I wouldn’t be able to reach him with my fists in my condition. He was expecting a fit in response to whatever it was he was about to say, but that just went to show that he hadn’t been paying attention to me at all. I was past rage, or rather it was past me. I couldn’t even strive for rage anymore. I mostly got out of bed because I had to pee and also because, really, I had no other choice. There were mouths to be fed, time cards to be punched. Sitting upright was the goal.

“You needed this. You should not be sleeping on the floor anymore.”

“Mary slept on the floor.”

Читать дальше