Yann Martel - Beatrice and Virgil

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Yann Martel - Beatrice and Virgil» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Beatrice and Virgil

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beatrice and Virgil: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beatrice and Virgil»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A famous author receives a mysterious letter from a man who is a struggling writer but also turns out to be a taxidermist, an eccentric and fascinating character who does not kill animals but preserves them as they lived, with skill and dedication – among them a howler monkey named Virgil and a donkey named Beatrice…

Beatrice and Virgil — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beatrice and Virgil», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Henry careened into the tigers and fell over. The pain ripping through his midriff was so intense and uncontrollable that he didn't so much get back onto his feet piecemeal as jerk himself up in one motion, as if he were a marionette pulled up by his strings. He made for the front door of the store as fast as he could. Would it be locked? The closer he got to the door, the more improbable it seemed that he would reach it. A hand would land on his shoulder. Worse, the taxidermist's blade would cut through his back.

Henry grappled with the doorknob. The door wasn't locked. It opened slowly and heavily. Henry threw himself out of the store and staggered across the pavement onto the street. Just then a car was approaching. He stood in front of it. The car braked and he collapsed onto its warm hood. Until then he may have been grunting. Now he was screaming as loudly as he could, though he was starting to snort and cough blood through his nose and mouth. The two women in the car came out, and when they saw the state he was in, they too started to scream. The man from the grocery store rushed out. Other people started appearing, alerted by the noise. Henry was surely safe now. Murder doesn't take place in the open, in front of so many witnesses, does it?

It was at that moment, as people blurrily crowded the edges of his vision, that Henry looked back at Okapi Taxidermy, still afraid the taxidermist might be following him. But he had stayed inside. The taxidermist was calmly looking out through the glass of the closed door, as if he were admiring the sunny day. Their eyes met. He smiled at Henry. It was a full smile that lit up his face. He had beautiful teeth. Henry barely recognized him. Was this the taxidermist's version of empty good cheer expressed in extremis? He turned and disappeared into his store, as if uninterested by the commotion at his doorstep. Henry collapsed, drowning in an internal sea of blood.

Even before the ambulance had arrived, the flames could be seen bursting out of Okapi Taxidermy. There was little the fire brigade could do. With that much wood and dry fur and so many flammable chemicals, the store burned quick and hard. A howling inferno.

With the taxidermist in it.

In a healthy individual, a broken bone that has healed properly is strongest where it was once broken. You have not lost any life, Henry told himself. You will still get your fair share of years. Yet the quality of his life changed. Once you've been struck by violence, you acquire companions that never leave you entirely: Suspicion, Fear, Anxiety, Despair, Joylessness. The natural smile is taken from you and the natural pleasures you once enjoyed lose their appeal. The city was ruined for Henry. Sarah, Theo and he would leave it soon. Only, where would they settle now?

Where would they find happiness? Where would he feel safe?

Henry regretted not having saved Beatrice and Virgil. He missed them with an ache that made itself felt even years later. It was the same kind of pain he felt when he had to be away for any length of time from Theo, a physical hunger for presence. He chided himself. Beatrice and Virgil, they didn't exist, not really; they were only characters in a play, animals at that, and dead ones. So what did that mean, save them? They were already lost by the time he had met them. But there it was: he missed them terribly. In his mind, he saw them as they stood in the taxidermist's workshop, Virgil so, Beatrice like this-he tried to make the pictures in his mind as clear as possible. But they faded, as memories of appearance always do.

All that remained now was their story, that incomplete story of waiting and fearing and hoping and talking. A love story, Henry concluded. Told by a madman whose mind he had never understood, but a love story nonetheless. Henry wished he had taken the taxidermist's play. That was another regret, that he had been so blinded by anger. But some stories are fated to be lost, at least in part.

Later on, on a few occasions, Henry looked at pictures of howler monkeys, nearly always photographed high up in tropical trees, but the evident wildness of the animals made it impossible for him to see anything of Virgil in them. Donkeys, on the other hand, were another matter. Once, at a Christmas Nativity scene with live animals, as Henry got close to the donkey, it looked at him and, as if recognizing him, shook its head and twisted its ears and made a gentle snuffling sound. Of course, it was likely only hoping for a treat. Henry knew that in his mind. Nonetheless, under his breath, he said her name-"Beatrice!"-and tears welled up in his eyes. He could never again see a donkey without thinking of Beatrice and Virgil and feeling grief and misery.

After the stabbing, Henry went about remembering and writing down exactly what had happened to him. To help his memory, he read up on taxidermy. Any bit of information that struck him as familiar, he noted; that's how he reassembled the essay the taxidermist had read to him. In a taxidermy magazine, he found an article on the taxidermist, with precious photos; these were the foundations for the mental reconstruction of Okapi Taxidermy. The essential part of the story, the taxidermist's play, was the most difficult to re-create. The sun of faith came before the generous wind, but which came first, the black cat or the three whispered jokes? The most elusive fragments on the sewing list were those the taxidermist had never discussed, such as the song, the food dish, the shirts with an arm missing, the porcelain shoes, the float in a parade. But bit by bit, painstakingly, Henry managed to reconstruct parts of the play.

At the hospital, as he was resting in his bed after the blood transfusions and the operation, the nurse presented him with a torn sheet of paper, crumpled and bloodied. She said it was Henry's, that he had brought it with him. Henry recognized what it was. As he turned after being stabbed, he must have laid a hand on the counter and unintentionally grabbed one of the pages from the taxidermist's play. Somewhere along the way, half of it had been torn off and lost.

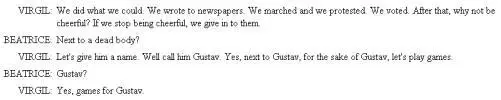

Through a handprint of blood, the words coming through the red like dark bruises on skin, Henry read the sole surviving element of the play, a fragment to do with the body Beatrice and Virgil find near the tree:

Henry first gave to the story of his stabbing the title A 20th-Century Shirt. Then he changed it to Henry the Taxidermist. Finally he settled on a title that went to the heart of the encounter: Beatrice and Virgil. It was to Henry a factual account, a memoir. But while in the hospital, before he started writing Beatrice and Virgil, Henry wrote another text. He called it Games for Gustav. It was too short to be a novel, too disjointed to be a short story, too realistic to be a poem. Whatever it was, it was the first piece of fiction Henry had written in years.

Games for Gustav

Your ten-year-old son is speaking to you.

He says he has found a way of obtaining some potatoes to feed your starving family.

If he is caught, he will be killed.

Do you let him go?

You are a barber.

You are working in a room full of people.

You shear them and then they are led away and killed.

You do this all day, every day. A new group is brought in.

You recognize the wife and sister of a good friend.

They recognize you too, with joy in their eyes. You embrace.

They ask you what is going to happen to them.

What do you tell them?

You are holding your granddaughter's hand.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beatrice and Virgil»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beatrice and Virgil» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beatrice and Virgil» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.