Yann Martel - Beatrice and Virgil

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Yann Martel - Beatrice and Virgil» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Современная проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Beatrice and Virgil

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Beatrice and Virgil: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Beatrice and Virgil»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A famous author receives a mysterious letter from a man who is a struggling writer but also turns out to be a taxidermist, an eccentric and fascinating character who does not kill animals but preserves them as they lived, with skill and dedication – among them a howler monkey named Virgil and a donkey named Beatrice…

Beatrice and Virgil — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Beatrice and Virgil», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Sarah was standing in the hallway, right where Mendelssohn used to stand, waiting for him, eyes open wide, anxious. But he didn't need to say anything. She saw right away the emptiness he brought back, the dramatic absence of life.

They both burst into tears. She'd returned exhausted from visiting a friend, she blubbered, and had gone straight to bed. Next she knew, Erasmus was barking furiously and Henry was shouting at her to stay in the bedroom. She hadn't noticed anything unusual with the animals when she'd returned home, but nor had she sought them out. She couldn't remember if she'd even seen Mendelssohn. She was too tired; she'd just wanted to have her nap. Maybe Erasmus hadn't attacked Mendelssohn yet. She blamed herself for not looking for her. Henry blamed himself for not taking proper note of Erasmus's character change, a sullenness that had not been there before.

Then there was the worry of having caught the disease themselves. Sarah was terrified of losing the baby, but Henry did most of the animal care and she was positive that she hadn't been bitten or even scratched by either Erasmus or Mendelssohn. Henry was sure he hadn't either, but since he had handled them in their last hours, he received a course of rabies vaccine shots.

One evening, a fellow actor from the play came up to him before rehearsal.

"Henry," he said, "I didn't know you were a famous writer. I thought you were just a waiter in a cafe."

He was speaking as if in jest, this hotshot lawyer actor friend, but Henry could tell his intent was serious. He was saying, Who are you? What is your standing in society? I thought I knew you, but apparently I don't. Was there resentment in his tone? Was Henry to be treated differently now? Was there something wrong in Henry having let a part of his identity remain unknown?

"Some guy was looking for you last time," continued the lawyer. "You'd already left. He said he knew you and kept on describing you but with the wrong name. He finally showed me the picture from the newspaper."

There'd been a photo from a rehearsal and a short article in the city paper the previous week. In spite of the makeup and the costume, and though his name was not given, Henry was clearly recognizable in it.

Henry had an inkling. "What was his name? Was he tall, older, very serious?"

"He wouldn't give his name. But that's him. As serious as an undertaker. You know him?"

"Yes, I know him."

"He had this for you," the lawyer said, handing Henry an envelope.

The envelope confirmed that it had indeed been the taxidermist. Why wouldn't he give his name? Henry wondered. He puzzled at the man's paranoia and secrecy. It hadn't occurred to him that the taxidermist didn't know his real name. Each time they'd seen each other, it was just the two of them and there had been no need to use names, real or fictitious.

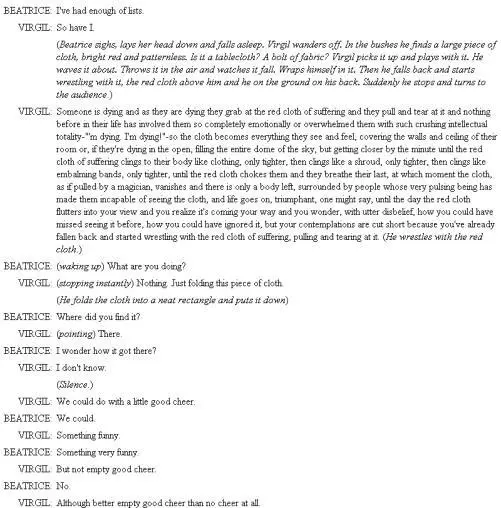

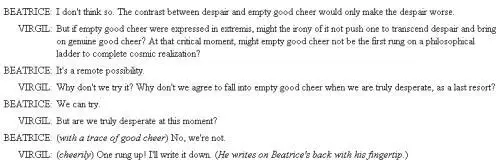

The envelope contained another scene from the taxidermist's play:

Henry looked over Virgil's soliloquy a second time. It was a single long sentence. He could imagine an actor getting into it, the energy building. The change of pronouns was effective, from "someone" and "they" to "you," hinging on "one" in the ironic "life goes on, triumphant, one might say." He remembered the "empty good cheer expressed in extremis" from the sewing kit. A typed note accompanied the scene. It was in the taxidermist's typical laconic style:

My story has no story.

It rests on the fact of murder.

There was neither salutation nor sign-off. Henry tried to figure out why the taxidermist had sent him that particular scene with this note. The red cloth of suffering-was that a sign of the taxidermist's own anxiety? As for the empty good cheer-was it a signal that he needed help, that he himself was feeling in extremis? Henry determined to go see him again soon.

Once Henry's "secret identity" was outed, relations with his fellow amateur actors weren't quite the same. Though Henry was exactly the same person he had been at the last rehearsal, he could tell that his fellow actors were looking at him differently. In conversations he was interrupted less often, perhaps, but he was also included less often. The director became alternately too hard on him or too soft. It was nothing unmanageable. Time and renewed familiarity would even things out once more. But it was a little stressful in the immediate run-up to an opening.

His music teacher knew. In the course of conversations before and after lessons, it had come out. His teacher had slapped his forehead and smiled. He'd read Henry's famous book. His daughter had offered it to him. He was proud of Henry, which was nice, and then during lessons he was exactly the same as he was before-except for the change in metaphors. Nothing so domestic as an ox anymore. Henry's clarinet was now a wild animal that needed taming.

Nathan the Wise opened with the usual mad rush to get everything ready in time, with the usual jitters, with the usual slipups, all accepted and forgiven in the name of "authenticity". The play ran Thursday to Sunday two weeks in a row and it went well, although one can never tell about a play in which one is a participant because one never sees the play oneself. The community press, at least, was positive.

And then Sarah's water broke. She heaved to the horizontal. Soon she was racked by contractions. They headed for the hospital. Over the course of the next twenty-four hours, she was reduced to a mucky animal who, after many pants, whimpers and screams, excreted from her body a pound of flesh, as the expression goes, that was red, wrinkled and slimy. The event couldn't have been more animal-like if the two of them had been in a muddy pen grunting. The thing produced, weakly gesticulating, looked half-simian, half-alien. Yet the call to Henry's humanity couldn't have been louder or more radical. He couldn't take his eyes off the baby. My son, my son Theo, thought Henry, dumbfounded.

Still, between the dying of Erasmus and Mendelssohn and the playing of Nathan the Wise and the arrival of Theo, Henry thought of the taxidermist and of his play. Something about his creative struggle heartened him. Even if their situations as writers could not be compared, here was a fellow Hephaestus struggling at the smithy.

And Henry thought of the taxidermist for another reason too, because one night his suspicions about the real subject matter of the play were confirmed.

It happened in the middle of the night, one frequently interrupted, as was the new routine, by Theo crying. The dislocations caused by the intense grief, stress and joy of the last weeks no doubt played a role. Whatever the psychological explanation, Henry was sleeping the sleep of the sleep-deprived when the name emerged in his head. It emerged so forcefully that it punctured his sleep and he sat up and awoke at the same moment, crying out: "Emmanuel Ringelblum!"

He stumbled to the computer and in a stupor of fatigue looked through his old flip-book essay. He found the reference to Ringelblum, but not the address. Next he searched through his research files, also on the computer. There too, with more details, he found what he had written on Ringelblum, but once again he had not noted the address. Finally he found it where he should have looked first, on the Internet, which is a net indeed, one that can be cast farther than the eye can see and be retrieved no matter how heavy the haul, its magical mesh never breaking under the strain but always bringing in the most amazing catch. He typed " 68 Nowolipki Street " in a search engine and there, in four tenths of a second, he had his answer.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Beatrice and Virgil»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Beatrice and Virgil» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Beatrice and Virgil» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.