The following evening at tea she told her mother and Rose the story. They were interested at first in the news that Nancy had been dancing two Sunday nights in succession with George Sheridan, but they became far more animated when Eilis told them about the rudeness of Jim Farrell.

"Don't go near that Athenaeum again," Rose said.

"Your father knew his father well," her mother said. "Years ago. They went to the races together a few times. And your father drank in Farrell's sometimes. It's very well kept. And his mother is a very nice woman, she was a Duggan from Glenbrien. It must be the rugby club has him that way, and it must be sad for his parents having a pup for a son because he's an only child."

"He sounds like a pup all right and he looks like one," Rose said.

"Well, he was in a bad mood last night anyway," Eilis said. "That's all I have to say. I suppose he might think that George should be with someone grander than Nancy."

"There's no excuse for that," her mother said. "Nancy Byrne is one of the most beautiful girls in this town. George would be very lucky to get her."

"I wonder would his mother agree," Rose said.

"Some of the shopkeepers in this town," her mother said, "especially the ones who buy cheap and sell dear, all they have is a few yards of counter and they have to sit there all day waiting for customers. I don't know why they think so highly of themselves."

Although Miss Kelly paid Eilis only seven and sixpence a week for working on Sundays, she often sent Mary to fetch her at other times-once when she wanted to get her hair done without closing the shop and once when she wanted all the tins on the shelves taken down and dusted and then replaced. Each time she gave Eilis two shillings but kept her for hours, complaining about Mary whenever she could. Each time also, as she left, Miss Kelly handed Eilis a loaf of bread, which Eilis knew was stale, to give to her mother.

"She must think we're paupers," her mother said. "What would we do with stale bread? Rose will go mad. Don't go there the next time she sends for you. Tell her you're busy."

"But I'm not busy."

"A proper job will turn up. That's what I'm praying for every day."

Her mother made breadcrumbs with the stale bread and roasted stuffed pork. She did not tell Rose where the breadcrumbs came from.

One day at dinnertime Rose, who walked home from the office at one and returned at a quarter to two, mentioned that she had played golf the previous evening with a priest, a Father Flood, who had known their father years before and their mother when she was a young girl. He was home from America on holidays, his first visit since before the war.

"Flood?" her mother asked. "There was a crowd of Floods out near Monageer, but I don't remember any of them becoming a priest. I don't know what became of them, you never see any of them now."

"There's Murphy Floods," Eilis said.

"That's not the same," her mother replied.

"Anyway," Rose said, "I invited him in for his tea when he said that he'd like to call on you and he's coming tomorrow."

"Oh, God," her mother said. "What would an American priest like for his tea? I'll have to get cooked ham."

"Miss Kelly has the best cooked ham," Eilis said, laughing.

"No one is buying anything from Miss Kelly," Rose replied. "Father Flood will eat whatever we give him."

"Would cooked ham be all right with tomatoes and lettuce, or maybe roast beef, or would he like a fry?"

"Anything will be fine," Rose said. "With plenty of brown bread and butter."

"We'll have it in the dining room, and we'll use the good china. If I could get a bit of salmon, maybe. Would he eat that?"

"He's very nice," Rose said. "He'll eat anything you put in front of him."

Father Flood was tall; his accent was a mixture of Irish and American. Nothing he said could convince Eilis's mother that she had known him or his family. His mother, he said, had been a Rochford.

"I don't think I knew her," her mother said. "The only Rochford we knew was old Hatchethead."

Father Flood looked at her solemnly. "Hatchethead was my uncle," he said.

"Was he?" her mother asked. Eilis saw how close she was to nervous laughter.

"But of course we didn't call him that," Father Flood said. "His real name was Seamus."

"Well, he was very nice," her mother said. "Weren't we awful to call him that?"

Rose poured more tea as Eilis quietly left the room, afraid that if she stayed she would be unable to disguise an urge to begin laughing.

When she returned she realized that Father Flood had heard about her job at Miss Kelly's, had found out about her pay and had expressed shock at how low it was. He inquired about her qualifications.

"In the United States," he said, "there would be plenty of work for someone like you and with good pay."

"She thought of going to England," her mother said, "but the boys said to wait, that it wasn't the best time there, and she might only get factory work."

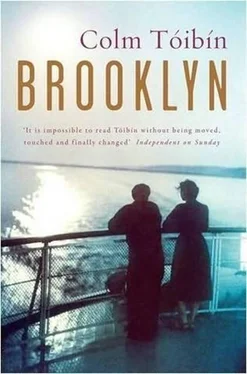

"In Brooklyn, where my parish is, there would be office work for someone who was hard-working and educated and honest."

"It's very far away, though," her mother said. "That's the only thing."

"Parts of Brooklyn," Father Flood replied, "are just like Ireland. They're full of Irish."

He crossed his legs and sipped his tea from the china cup and said nothing for a while. The silence that descended made it clear to Eilis what the others were thinking. She looked across at her mother, who deliberately, it seemed to her, did not return her glance, but kept her gaze fixed on the floor. Rose, normally so good at moving the conversation along if they had a visitor, also said nothing. She twisted her ring and then her bracelet.

"It would be a great opportunity, especially if you were young," Father Flood said finally.

"It might be very dangerous," her mother said, her eyes still fixed on the floor.

"Not in my parish," Father Flood said. "It's full of lovely people. A lot of life centres round the parish, even more than in Ireland. And there's work for anyone who's willing to work."

Eilis felt like a child when the doctor would come to the house, her mother listening with cowed respect. It was Rose's silence that was new to her; she looked at her now, wanting her sister to ask a question or make a comment, but Rose appeared to be in a sort of dream. As Eilis watched her, it struck her that she had never seen Rose look so beautiful. And then it occurred to her that she was already feeling that she would need to remember this room, her sister, this scene, as though from a distance. In the silence that had lingered, she realized, it had somehow been tacitly arranged that Eilis would go to America. Father Flood, she believed, had been invited to the house because Rose knew that he could arrange it.

Her mother had been so opposed to her going to England that this new realization came to Eilis as a shock. She wondered if she had not taken the job in the shop and had not told them about her weekly humiliation at Miss Kelly's hands, might they have been so ready to let this conversation happen. She regretted having told them so much; she had done so mostly because it had made Rose and her mother laugh, brightened a number of meals that they had had with each other, made eating together nicer and easier than anytime since her father had died and the boys had left. It now occurred to her that her mother and Rose did not think her working for Miss Kelly was funny at all, and they offered no word of demurral as Father Flood moved from praising his parish in Brooklyn to saying that he believed he would be able to find Eilis a suitable position there.

In the days that followed no mention was made of Father Flood's visit or his raising the possibility of her going to Brooklyn, and it was the silence itself that led Eilis to believe that Rose and her mother had discussed it and were in favour of it. She had never considered going to America. Many she knew had gone to England and often came back at Christmas or in the summer. It was part of the life of the town. Although she knew friends who regularly received presents of dollars or clothes from America, it was always from their aunts and uncles, people who had emigrated long before the war. She could not remember any of these people ever appearing in the town on holidays. It was a long journey across the Atlantic, she knew, at least a week on a ship, and it must be expensive. She had a sense too, she did not know from where, that, while the boys and girls from the town who had gone to England did ordinary work for ordinary money, people who went to America could become rich. She tried to work out how she had come to believe also that, while people from the town who lived in England missed Enniscorthy, no one who went to America missed home. Instead, they were happy there and proud. She wondered if that could be true.

Читать дальше