At first she thought that she should go to see Jim Farrell now, but then realized that he would be working behind the bar. She tried to imagine going into the pub and finding him there and trying to talk to him, or waiting while he found his father or his mother to take over the bar as she went out with him and told him that she was leaving. She could imagine his hurt, but she was unsure what exactly he would do, whether he would tell her that he would wait while she got a divorce and attempt to convince her to stay, or whether he would demand an explanation from her as to why she had led him on. Seeing him, she thought, would achieve nothing.

She thought of writing a note to say that she had to go back and posting it in the door of his house for him to find either late that night or in the morning. But if he found it that night, he would instantly seek her out. Instead, she decided, she would drop the note in the door the following morning on her way to the railway station. She would simply say that she had to go back and she was sorry and she would write when she arrived in Brooklyn and would explain her reasons.

She heard her mother coming back and walking slowly up the stairs to her room and she thought of following her, of asking her to stay with her while she packed, and talk to her. But there had been something, she thought, so steely and implacable about her mother's insistence that she wanted to say goodbye only once that Eilis knew it would be pointless now to ask for her blessing or whatever it was she wanted from her before she left this house.

In her room, she wrote the note to Jim Farrell, then left it aside; she pulled her suitcase out from under the bed and placed it on the bed and began to fill it with her clothes. She could imagine her mother listening as the wardrobe door was opened and hangers with clothes on them were pulled off the rail. She imagined her mother tensely following her as her footsteps crossed the room. The suitcase was almost full by the time she opened the drawer where she had kept Tony's letters. She took them and slipped them in at the side of the case. She would read the ones she had not opened on her journey across the Atlantic. For a moment, as she held the photographs taken that day in Cush, the one with her and Jim and George and Nancy, and the one of her alone with Jim as they smiled so innocently at the camera, she thought she would tear them up and put them in the bin downstairs. But then she thought better of it and slowly took all her clothes out of the case and placed the two photographs face down safely at the bottom of the case and then covered them over again. Some time in the future, she thought, she would look at them and remember what would soon, she knew now, seem like a strange, hazy dream to her.

She closed the case, carried it downstairs and left it in the hallway. It was still bright outside, and, as she sat at the kitchen table having something to eat, the last rays of the sun came through the window.

A few times over the hours that followed she was tempted to carry up a tray with tea and biscuits or sandwiches to her mother; her mother's door remained closed and there was not a sound from the room. She knew that if she knocked on the door, or opened it, her mother would firmly tell her that she did not want to be disturbed. Later, when she decided to go to bed, Eilis passed the door of Rose's room and thought to enter, to look for the last time at the place where her sister had died, but, although she stopped outside for a second and lowered her eyes in a sort of reverence, she did not open the door.

As she had not drawn the curtains she was woken by the morning light. It was early and there was no sound except for bird-song. She knew that her mother would be awake too, listening for every sound. She moved quietly, carefully, putting on the fresh clothes she had left out for herself, going downstairs to stuff the old clothes with her toiletries into the suitcase. She checked that she had everything-money, her passport, the letter from the shipping company and the note for Jim Farrell. Quietly, she sat in the front parlour to watch out for Joe Dempsey's car.

When it arrived, she made sure she was at the door before he knocked. She put her finger to her lips to indicate that they should not speak. He put the suitcase in the boot of the car as she left her key to the house on the hallstand. As they drove away, she asked him to stop for a moment at Farrell's in Rafter Street, and, when he did so, she dropped the note through the letter box of the hall door.

As the train moved south, following the line of the Slaney, she imagined Jim Farrell's mother coming upstairs with the morning post. Jim would find her note among bills and business letters. She imagined him opening it and wondering what he should do. And at some stage that morning, she thought, he would come to the house in Friary Street and her mother would answer the door and she would stand watching Jim Farrell with her shoulders back bravely and her jaw set hard and a look in her eyes that suggested both an inexpressible sorrow and whatever pride she could muster.

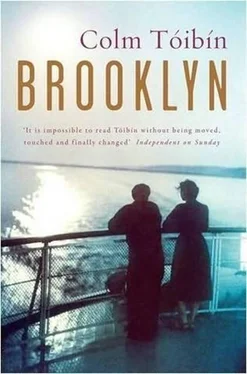

"She has gone back to Brooklyn," her mother would say. And, as the train rolled past Macmine Bridge on its way towards Wexford, Eilis imagined the years ahead, when these words would come to mean less and less to the man who heard them and would come to mean more and more to herself. She almost smiled at the thought of it, then closed her eyes and tried to imagine nothing more.

Colm Toibin was born in Ireland in 1955. He is the author of the novels The South, The Heather Blazing and The Story of the Night. He has also written the non-fiction books Bad Blood, Homage to Barcelona and The Sign of the Cross. The Blackwater Lightship was shortlisted for the 1999 Booker Prize. Colm Toibin lives in Dublin.

***