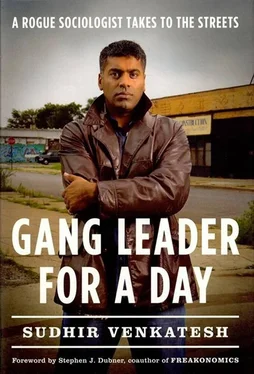

It wasn’t as if I had any intention of joining the gang in an actual drive-by shooting (nor would they ever invite me). But since I could get in trouble just for driving around with them while they talked about shooting somebody, I had to rethink my approach. I would especially have to be clearer with J.T. We had spoken several times about my involvement; when I was gang leader for a day, for instance, he knew my limits and I understood his. But now I would need to tell him, and perhaps a few others, about the fact that I was legally obligated to share my notes if I was ever subpoenaed.

This legal advice was ultimately helpful in that it led me to seriously take stock of my research. It was getting to be time for me to start thinking about the next stage: writing up my notes into a dissertation. I had become so involved in the daily drama of tagging along with Ms. Bailey and J.T. that I’d nearly abandoned my study of the broader underground economy my professors wanted to be the backbone of my research.

So I returned to Robert Taylor armed with two objectives: let people know about my legal issues and glean more details of the tenants’ illegal economic activities.

I figured that most people would balk at revealing the economics of hustling, but when I presented the idea to J.T., Ms. Bailey, and several others, nearly everyone agreed to cooperate. Most of the hustlers liked being taken seriously as businesspeople-and, it should be said, they were eager to know if they earned more than their competitors. I emphasized that I wouldn’t be able to share the details of anyone else’s business, but most people just shrugged off my caveat as a technicality that could be gotten around.

So with the blessing of J.T. and Ms. Bailey, I began devoting my time to interviewing the local hustlers: candy sellers, pimps and prostitutes, tailors, psychics, squeegee men.

I also told J.T. and Ms. Bailey about my second problem, my legal obligation to share notes with the police.

“You mean you didn’t know this all along?” Ms. Bailey said. “Even I knew that you have to tell police what you’re doing-unless you give them information on the sly.”

“Oh, no!” I protested. “I’m not going to be an informant.”

“Sweetheart, we’re all informants around here. Nothing to be ashamed of. Just make sure that you get what you need, I always say. And don’t let them beat you up.”

“I’m not sharing my data with them-that’s what I mean.”

“You mean you’ll go to prison?”

“Well, not exactly. I just mean I won’t share my data with them.”

“Do you know what being in contempt means?”

When I didn’t reply, Ms. Bailey shook her head in disgust. I had seen this look before: she was wondering how I had qualified for higher education given my lack of street smarts.

“Any nigger around here can tell you that you got two choices,” she said. “Tell them what they want or sit in Cook County Jail.”

I was silent, trying to think of a third option.

“I’ll ask you again,” she said. “Will you give up your information, or will you agree to go to jail?”

“You need to know that? That’s important to you?”

“Sudhir, let me explain something to you. You think we were born yesterday around here. Haven’t we had this conversation a hundred times? You think we don’t know what you do? You think we don’t know that you keep all your notebooks in Ms. Mae’s apartment?”

I shuddered. Ms. Mae had made me feel so comfortable in her apartment that I’d never even entertained the possibility that someone like Ms. Bailey would think about-and perhaps even page through-my notebooks.

“So why let me hang out?” I asked.

“Why do you want to hang out?”

“I suppose I’m learning. That’s what I do, study the poor.”

“Okay, well, you want to act like a saint, then you go ahead,” Ms. Bailey said, laughing. “Of course you’re learning! But you are also hustling. And we’re all hustlers. So when we see another one of us, we gravitate toward them. Because we need other hustlers to survive.”

“You mean that people think I can do something for them if they talk to me?”

“They know you can do something for them!” she yelped, leaning across the table and practically spitting out her words. “And they know you will, because you need to get your information. You’re a hustler, I can see it. You’ll do anything to get what you want. Just don’t be ashamed of it.”

I tried to turn the conversation back to the narrow legal issue, but Ms. Bailey kept on lecturing me.

“I’ll be honest with you,” she said, sitting back in her chair. “If you do tell the police, everyone here will find you and beat the shit out of you. So that’s why we know you won’t tell nobody.” She smiled as if she’d won the battle.

So who should I be worried about? I wondered. The police or Ms. Bailey and the tenants?

When I told J.T. about my legal concerns, he looked at me with some surprise. “I could’ve told you all that!” he said. “Listen, I’m never going to tell you anything that’s going to land me in jail-or get me killed. So it don’t bother me what you write down, because I can take care of myself. But that’s really not what you should be worried about.”

I waited.

“What you should be asking yourself is this: ‘Am I going to be on the side of black folks or the cops?’ Once you decide, you’ll do whatever it takes. You understand?”

I didn’t.

“Let me try again. Either you’re with us-you feel like you’re in this with us and you respect that-or you’re just here to look around. So far these niggers can tell that you’ve been with us. You come back every day. Just don’t change, and nothing will go wrong, at least not around here.”

J.T.’s advice seemed vague and a bit too philosophical. Ms. Bailey’s warning-that I would get beat up if I betrayed confidences- made more sense. But maybe J.T. was saying the same thing, in his own way.

I decided to focus my study of the underground economy on the three high-rise buildings that formed the core of J.T.’s territory. I already knew quite a bit-that squatters fixed cars in the alleys, people sold meals out of their homes, and prostitutes took clients to vacant apartments-but I had never asked people how much money they made, what kind of expenses they incurred, and so on.

J.T. was far more enthusiastic about my project than I’d imagined he would be, although I couldn’t figure out why.

“I have a great idea,” he told me one day. “I think you should talk to all the pimps. Then you can go to all the whores. Then I’ll let you talk to all the people stealing cars. Oh, yeah! And you also have folks selling stolen stuff. I mean, there’s a whole bunch of people you can talk to about selling shoes or shirts! And I’ll make sure they cooperate with you. Don’t worry, they won’t say no.”

“Well, we don’t want to force anyone to talk to me,” I said, even though I was excited about meeting all these people. “I can’t make anyone talk to me.”

“I know,” J.T. said, breaking into a smile. “But I can.”

I laughed. “No, you can’t do that. That’s what I’m saying. That wouldn’t be good for my research.”

“Fine, fine,” he said. “I’ll do it, but I won’t tell you.”

J.T. arranged for me to start interviewing the pimps. He explained that he taxed all the pimps working in or around his buildings: some paid a flat fee, others paid a percentage of their take, and all paid in kind by providing women to J.T.’s members at no cost. The pimps had to pay extra, of course, if they used a vacant apartment as a brothel; they even paid a fee to use the stairwells or a parking lot.

As I began interviewing the pimps, I also befriended some of the freelance prostitutes like Clarisse who lived and worked in the building. “Oh, my ladies will love the attention,” Clarisse said when I asked for help in talking to these women. Within two weeks I had interviewed more than twenty of them.

Читать дальше