“I think I get it.” I sat silently and stared into my hands. “When do you think I should see these things?”

“Well, why do you want to see what we do? I mean, why don’t you hang around the police? You should figure out why they don’t come.”

“Ms. Bailey, I wanted to ask you about that. Did you really call the police? Or the ambulance?”

“Sudhir, the hardest thing for middle-class white folk to understand is why those people don’t come when we call.”

Ms. Bailey didn’t think I was actually white, but she always tried to show me how my middle-class background got in the way of understanding life in the projects.

“They just don’t come around all the time. And so we have to find ways to deal with it. I’m not sure how much better I can explain it to you. Why don’t you watch out for the next few months? See how much they come around.”

“What about Officer Reggie?”

“Yes, he’s a friend. But can I tell you how he can be helpful? Not by coming and putting Bee-Bee in jail. Because he’ll be out in the morning. But Officer Reggie can visit Bee-Bee after we’re through with him. Maybe put the fear in him.”

“Put the fear in him? I don’t understand.”

“He could visit Bee-Bee and tell him that we won’t be so nice the next time he does that to ’Neesha. If Bee-Bee knows that the cop don’t care if we kick his ass, that may make him think twice. That is what we need Officer Reggie for.”

“Ms. Bailey, I have to tell you that I just don’t get it. I’ve been watching you for a while, and it just seems to me that you shouldn’t have to be doing everything you’re doing. If you got the help you needed, you wouldn’t have to act like this.”

“Sudhir, what’s the first thing I told you when you asked about my job?”

I smiled as I thought of something she’d told me months earlier: “As long as I’m helping people, something ain’t right about this community. When they don’t need me no more, that’s when I know they’re okay.”

But she’d been helping for three decades and didn’t see any end in sight.

One day in the middle of February, the Wilson family lost their front door. The Wilsons lived on the twelfth floor, just down the hall from Ms. Bailey. Their door simply fell off its hinges, leaving the family exposed to the brutal cold of a Chicago winter.

Even with a front door, the Robert Taylor Homes weren’t very comfortable in the winter. Because the galleries are outdoors, you can practically get blown over by the lake wind as you walk from the elevator to your apartment. Inside, the winter wind inevitably finds its way through the seams in the doorframe.

Chris Wilson worked for the city and moved in and out of Robert Taylor, living off-the-lease with his wife, Mari, and her six children. Chris and Mari were, unsurprisingly, pretty anxious when they lost their door. It wasn’t just the cold; they were worried about being robbed. It was common knowledge that drug addicts would pounce on any opportunity to steal a TV or anything else of value.

The Wilsons tried calling the CHA but got no response. They put up a makeshift door of wooden planks and plastic sheeting, but it didn’t keep out the cold. Neighbors who said they’d keep an eye on the apartment didn’t show up reliably. So after a few days, the Wilsons called Ms. Bailey.

Ms. Bailey leaped into action. She asked J.T. to station a few of his gang members in the twelfth-floor stairwells to keep out potential burglars. As a preventive measure, J.T. also shut down a nearby vacant apartment that was being used as a crack den. Then Ms. Bailey contacted two people she knew at the CHA. The first was a man who obtained a voucher so the Wilsons could stay at an inexpensive motel until their door was fixed. The second person was able to speed up the requisition process for obtaining a new door. It arrived two days after Ms. Bailey placed her first call.

The door didn’t come cheap for the Wilsons. They had to pay Ms. Bailey several hundred dollars, which covered the fees that she paid to her CHA friends, as well as an electrician’s bill, since some of the wiring in the Wilsons’ apartment went bad because of the cold. Ms. Bailey presumably pocketed the rest of the money. Mari Wilson was, on balance, unperturbed. “Last summer we didn’t have running water for a month,” she told me, “so one week without a door was nothing.”

Having watched Ms. Bailey help women like Taneesha and families like the Wilsons, I was left with deeply mixed feelings about her methodology-often ingenious and just as often morally questionable. With such scarce resources available, I understood why she believed that the ends justified the means. But collaborating with gangs, bribing officials for services, and redistributing drug money did little to help the typical family in her building. Ms. Bailey had told me that she would much rather play by the rules if only the rules worked. But in the end I concluded that what really drove Ms. Bailey was a thirst for power. She liked the fact she could get things done (and get paid for it), and she wasn’t about to give that up, even if it meant that sometimes her families might get short shrift. Many families, meanwhile, were too scared to challenge her and invite the consequences of her wrath.

I was left discouraged by the sort of power bestowed upon building presidents like Ms. Bailey. People in this community shouldn’t have to wait more than a week to get a new front door. People in this community shouldn’t have to wonder if the ambulance or police would bother responding. People in this community shouldn’t have to pay a go-between like Ms. Bailey to get the services that most Americans barely bother to think about. No one in the suburb where I grew up would tolerate such inconvenience and neglect.

But life in the projects wasn’t like my life in the suburbs. Not only was it harder, but it was utterly unpredictable, which necessitated a different set of rules for getting by. And living in a building with a powerful tenant leader, as hard as that life could be, was slightly less hard. It may have cost a little more to get what you needed, but at least you had a chance.

SIX. The Hustler and the Hustled

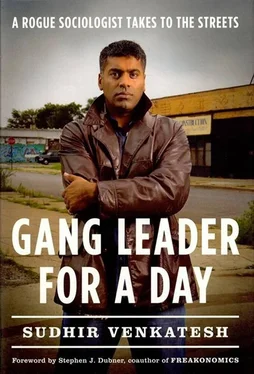

Four years deep into my research, it came to my attention that I might get into a lot of trouble if I kept doing what I’d been doing.

During a casual conversation with a couple of my professors, in which I apprised them of how J.T.’s gang went about planning a drive-by shooting-they often sent a young woman to surreptitiously cozy up to the rival gang and learn enough information to prepare a surprise attack-my professors duly apprised me that I needed to consult a lawyer. Apparently the research I was doing lay a bit out of bounds of the typical academic research.

Bill Wilson told me to stop visiting the projects until I got some legal advice. I tried to convince Wilson to let me at least hang out around the Boys & Girls Club, but he shot me a look indicating that his position was not negotiable.

I did see a lawyer, and I learned a few important things.

First, if I became aware of a plan to physically harm somebody, I was obliged to tell the police. Meaning I could no longer watch the gang plan a drive-by shooting, although I could speak with them about drive-bys in the abstract.

Second, there was no such thing as “researcher-client confidentiality,” akin to the privilege conferred upon lawyers, doctors, or priests. This meant that if I were ever subpoenaed to testify against the gang, I would be legally obligated to participate. If I withheld information, I could be cited for contempt. While some states offer so-called shield laws that allow journalists to protect their confidential sources, no such protection exists for academic researchers.

Читать дальше