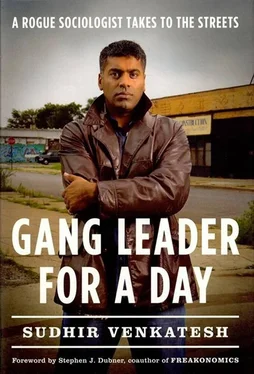

Sudhir Venkatesh

Gang Leader for a Day

Stephen J. Dubner

I believe that Sudhir Venkatesh was born with two abnormalities: an overdeveloped curiosity and an underdeveloped sense of fear.

How else to explain him? Like thousands upon thousands of people, he entered graduate school one fall and was dispatched by his professors to do some research. This research happened to take him to the Robert Taylor Homes in Chicago, one of the worst ghettos in America. But blessed with that outlandish curiosity and unfettered by the sort of commonsensical fear that most of us would experience upon being held hostage by an armed crack gang, as Venkatesh was early on in his research, he kept coming back for more.

I met Venkatesh a few years ago when I interviewed him for Freakonomics, a book I wrote with the economist Steve Levitt. Venkatesh and Levitt had collaborated on several academic papers about the economics of crack cocaine. Those papers were interesting, to be sure, but Venkatesh himself presented a whole new level of fascination. He is soft-spoken and laconic; he doesn’t volunteer much information. But every time you ask him a question, it is like tugging a thread on an old tapestry: the whole thing unspools and falls at your feet. Story after story, marked by lapidary detail and hard-won insight: the rogue cop who terrorized the neighborhood, the jerry-built network through which poor families hustled to survive, the time Venkatesh himself became gang leader for a day.

Although we wrote about Venkatesh in Freakonomics (it was many readers’ favorite part), there wasn’t room for any of these stories. Thankfully, he has now written an extraordinary book that details all his adventures and misadventures. The stories he tells are far stranger than fiction, and they are also more forceful, heartbreaking, and hilarious. Along the way he paints a unique portrait of the kind of neighborhood that is badly misrepresented when it is represented at all. Journalists like me might hang out in such neighborhoods for a week or a month or even a year. Most social scientists and dogooders tend to do their work at arm’s length. But Venkatesh practically lived in this neighborhood for the better part of a decade. He brought the perspective of an outsider and came away with an insider’s access. A lot of writing about the poor tends to reduce living, breathing, joking, struggling, sensual, moral human beings to dupes who are shoved about by invisible forces. This book does the opposite. It shows, day by day and dollar by dollar, how the crack dealers, tenant leaders, prostitutes, parents, hustlers, cops, and Venkatesh himself tried to construct a good life out of substandard materials.

As much as I have come to like Venkatesh, and admire him, I probably would not want to be a member of his family: I would worry too much about his fearlessness. I probably wouldn’t want to be one of his research subjects either, for his curiosity must be exhausting. But I am very, very happy to have been one of the first readers of Venkatesh’s book, for it is as extraordinary as he is.

I woke up at about 7:30 A.M. in a crack den, Apartment 1603 in Building Number 2301 of the Robert Taylor Homes. Apartment 1603 was called the “Roof,” since everyone knew that you could get very, very high there, even higher than if you climbed all the way to the building’s actual rooftop.

As I opened my eyes, I saw two dozen people sprawled about, most of them men, asleep on couches and the floor. No one had lived in the apartment for a while. The walls were peeling, and roaches skittered across the linoleum floor. The activities of the previous night-smoking crack, drinking, having sex, vomiting-had peaked at about 2:00 A.M. By then the unconscious people outnumbered the conscious ones-and among the conscious ones, few still had the cash to buy another hit of crack cocaine. That’s when the Black Kings saw diminishing prospects for sales and closed up shop for the night.

I fell asleep, too, on the floor. I hadn’t come for the crack; I was here on a different mission. I was a graduate student at the University of Chicago, and for my research I had taken to hanging out with the Black Kings, the local crack-selling gang.

It was the sun that woke me, shining through the Roof’s doorway. (The door itself had disappeared long ago.) I climbed over the other stragglers and walked down to the tenth floor, where the Patton family lived. During the course of my research, I had gotten to know the Pattons-a law-abiding family, it should be said-and they treated me kindly, almost like a son. I said good morning to Mama Patton, who was cooking breakfast for her husband, Pops, a seventy-year-old retired factory worker. I washed my face, grabbed a slice of cornbread, and headed outside into a breezy, brisk March morning.

Just another day in the ghetto.

Just another day as an outsider looking at life from the inside. That’s what this book is about.

ONE. How Does It Feel to Be Black and Poor?

During my first weeks at the University of Chicago, in the fall of 1989, I had to attend a variety of orientation sessions. In each one, after the particulars of the session had been dispensed with, we were warned not to walk outside the areas that were actively patrolled by the university’s police force. We were handed detailed maps that outlined where the small enclave of Hyde Park began and ended: this was the safe area. Even the lovely parks across the border were off-limits, we were told, unless you were traveling with a large group or attending a formal event.

It turned out that the ivory tower was also an ivory fortress. I lived on the southwestern edge of Hyde Park, where the university housed a lot of its graduate students. I had a studio apartment in a ten-story building just off Cottage Grove Avenue, a historic boundary between Hyde Park and Woodlawn, a poor black neighborhood. The contrast would be familiar to anyone who has spent time around an urban university in the United States. On one side of the divide lay a beautifully manicured Gothic campus, with privileged students, most of them white, walking to class and playing sports. On the other side were down-and-out African Americans offering cheap labor and services (changing oil, washing windows, selling drugs) or panhandling on street corners.

I didn’t have many friends, so in my spare time I started taking long walks, getting to know the city. For a budding sociologist, the streets of Chicago were a feast. I was intrigued by the different ethnic neighborhoods, the palpable sense of culture and tradition. I liked that there was one part of the city, Rogers Park, where Indians, Pakistanis, and Bangladeshis congregated. Unlike the lily-white suburbs of Southern California where I’d grown up, the son of immigrants from South Asia, here Indians seemed to have a place in the ethnic landscape along with everyone else.

I was particularly interested in the poor black neighborhoods surrounding the university. These were neighborhoods where nearly half the population didn’t work, where crime and gang activity were said to be entrenched, where the welfare rolls were swollen. In the late 1980s, these isolated parts of the inner cities gripped the nation’s attention. I went for many walks there and started playing basketball in the parks, but I didn’t see any crime, and I didn’t feel particularly threatened. I wondered why the university kept warning students to keep out.

As it happened, I attracted a good bit of curiosity from the locals. Perhaps it was because these parks didn’t attract many nonblack visitors, or perhaps it was because in those days I dressed like a Deadhead. I got asked a lot of questions about India-most of which I couldn’t answer, since I’d moved to the States as a child. Sometimes I’d come upon a picnic, and people would offer me some of their soul food. They were puzzled when I turned them down on the grounds that I was a vegetarian.

Читать дальше