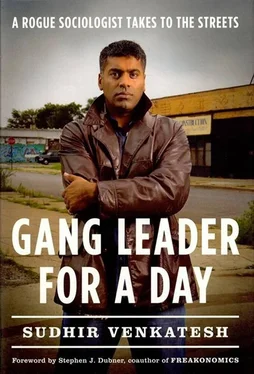

“Sudhir,” J.T. said, “you have to realize that if you do that, then you lose respect. They need to see that you are the boss, which means that you hand out the beating.”

“What if I make them do twenty pushups or fifty squat thrusts? Or maybe they have to clean my car.”

“You don’t own a car,” J.T. said.

“That’s right-so they have to clean your car for a month!”

“Listen, these guys already clean my car, wipe my ass, whatever I want, so that ain’t happening,” J.T. said calmly, as if wanting to make sure I understood the breadth of his power. “And if they can steal money or not pay somebody for working and they only have to clean a car, then think how much these guys will steal. You have to make sure they understand that they can’t be stealing! Nigger, they need to fear you.”

“So that’s your leadership style? Fear?” I was trying to give the impression that I had my own style. Mostly, I was stalling out of worry that I’d have to throw a punch. “Fear, huh? Very interesting, very interesting.”

We pulled up to the street corner where Billy and Otis had been told to meet us. It was cold, not quite noon, but the sun had broken through a bit. Aside from a nearby gas station, the corner was surrounded mostly by empty lots and abandoned buildings.

I watched Billy and Otis saunter over. Billy was about six foot six. He had been a star basketball player at Dunbar High School and won a scholarship to Southern Illinois at Carbondale, a small downstate school. He began using his connections with the Black Kings to deal marijuana and cocaine to students in his dorm. He eventually decided to quit the basketball team to sell drugs full-time. He once told me that the lure of cash “made my mouth water, and I couldn’t get enough of it. Dumbest move I ever made.” Now he was working in the gang to save money in hopes of returning to college.

I always liked Billy. He was one of thousands of people in this neighborhood who, by the time they turned eighteen, had made all sorts of important decisions by themselves. Fewer than 40 percent of the adults in the neighborhood had even graduated from high school, much less college, so Billy didn’t have a lot of places to go for counsel. Even so, he was the first one to accept responsibility for the bad decisions he’d made. I’ll never forget what he said when he moved back to the projects after dropping out of college: “I just needed someone to talk to. My mind was racing out of control, and I had no one to talk to.”

I didn’t want to think about hitting Billy today, because I really liked him-and because, at that height, his jaw was nearly out of reach.

Otis was a different story. He always wore dark sunglasses-even indoors, even in winter-and he kept a large knife underneath a long black jacket that he always wore, even in hot weather. He loved to cut people up and give them a scar. And he didn’t like me at all.

This acrimony stemmed from a basketball game several months earlier. I regularly attended the gang’s midnight games at the Boys & Girls Club. If Autry came up one referee short, he sometimes pressed me into service. I had played basketball growing up, but not how it was played in the ghetto. In my neighborhood we set picks, passed the ball-and, perhaps most important, called fouls, even in pickup games. In the gang games, if you called even half the fouls that were actually committed, you’d run out of players by halftime. But during one game I refereed when Otis was playing, I called five quick fouls on him because… well, because he fouled somebody five times. He had to leave the game.

From the bench, with a cheap bottle of liquor in his hand, Otis shouted at me, “I’m going to kill you, motherfucker! I’m going to cut your balls off!” It was pretty hard to concentrate for the rest of the game.

I left the gym immediately afterward, but Otis chased me down in the parking lot. He was still in his uniform, so he didn’t have his machete with him. He picked up a bottle from the asphalt, smashed it, and pressed the jagged edge to my neck. Just then Autry hustled into the parking lot, pulled Otis back, and told me to run. I stood there in shock while Autry kept yelling, “Run, nigger, run!” After about thirty seconds, he and Otis both started laughing, because my feet simply wouldn’t move. They laughed so hard that they crumpled to the ground. I nearly threw up.

I was thinking of this incident now, as Otis walked toward us, and I wondered if he was, too. I got out of the car along with J.T. and Price.

“Okay, let’s hear what happened,” J.T. said. “I need to know who fucked up last week. Billy, you first.”

J.T. seemed preoccupied, maybe a little upset. I didn’t know why, and it wasn’t the time to ask. It certainly didn’t seem as if I had much chance of leading the conversation.

“Like I already said,” Billy began, “ain’t nothing to say. Otis got a hundred-pack and was a hundred dollars short. I want my money.” He was stubborn and defiant.

“Nigger, please,” Otis said. “You ain’t paid me for a week. You owed me that money.” Otis’s eyes were bloodshot, and he looked as if he might reach out and hit Billy at any moment.

“Didn’t pay?” said Billy. “You’re wrong on that. I paid you, and you went out that night partying. I remember.”

The director of a sales team-in this case, Billy-usually gave his street dealers an allotment of prepackaged crack. A “100-pack” was the standard. A single bag sold for ten dollars, so once the dealer exhausted his inventory, he was supposed to give his director one thousand dollars. Billy was saying that Otis had turned over just nine hundred dollars. Otis’s only defense seemed to be that Billy owed him money from an earlier transaction-a charge that Billy denied. Otis and Billy kept arguing with each other, but they were looking at J.T., Price, and me, pleading their cases.

“Okay, okay!” J.T. said. “This ain’t going nowhere. Get the fuck out of here. I’ll be back with you later.”

Billy and Otis walked away, joining the rest of their crew near some Dumpsters where they stored their drugs and money. Once they were out of earshot, J.T. turned to me: “Well, what do you think? You heard enough?”

“Yes, I did!” I said proudly. “Here’s my decision: Otis clearly took the money and pocketed it. You notice that he never actually denied taking something. He just said that he was owed the money by Billy. Now, I can’t tell whether Billy never paid Otis for the day’s work, but the fact that Otis didn’t deny stealing the money makes me feel that Billy forgot to pay Otis-or maybe he didn’t want to. But all that doesn’t matter, because Otis did steal some money. And, I bet, Billy didn’t pay.”

There was silence for about thirty seconds. Finally Price spoke up. “Hey, I like it. Not bad. That was the smartest thing you said all day!”

“Yeah,” said J.T. “Now, what’s the penalty?”

“Well, in this case we borrow from the NFL and invoke the offsetting-penalty rule,” I said. “Both guys screwed up, so the two penalties cancel each other out. I know that Otis’s crime is more serious because he stole, but both of them messed up. So no one gets hurt or pays a fine. How about that?”

More silence. Price watched J.T. for his reaction. I did the same. “Tell Otis to come over here,” J.T. finally said. Price went to fetch him.

“What are you going to do?” I asked J.T. He said nothing. “C’mon, tell me.” He ignored me.

Price returned with Otis.

“Wait for me over there,” J.T. told me quietly, nodding toward the car.

I did as he said. I climbed into the backseat, which faced away from J.T. and the others. Still, I was close enough to hear J.T. tell Otis to put his hands behind his back. Then I heard a punch, fist hitting cheekbone, and after about ten seconds another one. Then, slowly, two more punches. I looked behind me through the back window and saw Otis, bent over, holding his face. J.T. was slowly walking back toward the car, shaking his fist. He got in, and then Price did, too.

Читать дальше